The Black-Boxed Ideology of AWE

Antonio Hamilton and Finola McMahon

Discussion

As we stated previously, AWE mediates student and instructor activity (Huang & Wilson, 2021; Wilson et al., 2021). As such, it is vital to document the functions and affordances of AWE, so that we can utilize AWE to its fullest potential, while addressing the issues these technologies might create. Even if the functions and affordances change, our themes highlight the inconsistency and black-boxing in the creation of Automated Writing Evaluation Programs.

We found that black-boxing occurs through inconsistent features, such that users cannot compare across programs or expect two programs to provide consistent feedback to the same input. The programs studied also made use of undefined terms, classified here as jargon, which limited a user's ability to understand the feedback they are given, even as the AWE may appear to explain its output. Finally, the programs' use of tiered subscription services limits testing prior to use, further black-boxing the AWE.

Discussion Point 1: Technical illiteracy is used to appeal to audiences who can buy software, such as school administrators

Notably, VWT became slightly less black-boxed for us specifically, as a result of Nicholas Walker's willingness to discuss his program directly and explain the process he used. We might also note that Walker is a teacher who was designing VWT with his own students and colleagues in mind. His willingness to share the details of his project may be related to the fact that he is not a corporation trying to develop a software for profit, but a teacher trying to better serve his students. Protecting proprietary materials may not be a priority to Walker in the way it is to a corporation like ETS. While the issue of technical illiteracy (Burrell, 2016) might not allow many users to truly understand how VWT functions, Walker's willingness to share the details of his program's creation does help in the "unboxing" process

However, other programs create black-boxing via assessment terminology. The AWE's use of jargon and the naming of different 'assessment categories' function as a form of black-boxing through functional or technical illiteracy. When WTL says that they check for "Extraneous Information," there is no clear way to tell what that actually assesses from the name itself, it is company-specific jargon. (Because WTL is behind a proprietary paywall, users cannot even test for what the category is looking for unless they are a paying customer.) If users cannot understand the feedback feature due to the jargon used, they cannot fully understand the feedback they are given and will not be able to critically apply the feedback to improve their writing.

This issue extends to the assessment terms which users might assume are commonly understood, such as "Grammar." Because the AWE do not provide definitions of these terms or hide those definitions behind a paywall, an administrator purchasing the program may expect that the use of the assessment terms matches their expectations. In the case of "Grammar" specifically, purchasers are left to assume their own meaning of the term, allowing the programs to obfuscate the complexity of grammar and the existence of many forms of grammar and many forms of Englishes. These algorithms actively hide the truth is that there is no one universal grammar, but many different rule sets for English grammar (Conference on College Composition and Communication, 1974). This could result in an AWE being utilized to prioritize white Englishes, and if administrators are unaware of the way grammar is being defined, they cannot account for or address that prioritization, potentially resulting in the continued centering of white language in education. Even when definitions are provided, they lack consistency and are implemented differently across different AWE. This further emphasizes that when the assessment categories appear to be easily understood, like "Grammar," they are still slightly opaque. It would be easy for many users to look at that category and imagine grammar as a standard, universal set of rules, but the simplicity of the assessment term in many of these AWE hides the underlying questions of the many types of Englishes used around the world and within countries and communities.

This lack of concrete definitions continue to be an issue even in the case of the AWE's "Plagiarism" checkers, which should arguably result in straightforward feedback. The "Plagiarism" checkers included by the AWE in the study theoretically must have a vast data bank of sample texts to compare student writing against. However, at the time of our data collection, none of the AWE studied provided information on what that sample input included or how it was collected. Are they scanning the internet to check for uncited repetition? Do they save past papers to compare against? This becomes an issue because it is hard to understand how the "Plagiarism" check might be functioning, as well as the effectiveness of a "Plagiarism" checker. Additionally, there is the question of exactly when something is considered plagiarism. If a student quotes something but has an error in their in-text or end-of-text citation, will the AWE consider that to be plagiarism? (And if so, how are they determining what the 'correct' citation would look like, given the common errors and issues in online citation generation programs.) The amount a writer would need to paraphrase a concept to avoid potential plagiarism may vary depending on the AWE used. The programs provide no information about the input involved in their "Plagiarism" checker or its functioning, further black-boxing the software and complicating its use. The answers to these questions are exceptionally important, given that the majority of these AWE target academic audiences, at least in part. If the "Plagiarism" checker is not accurate or does not mirror the plagiarism assessment of a student's teacher, they could be punished for plagiarism in a situation where they thought they had cited appropriately. This issue with plagiarism checkers is representative of a larger issue with the lack of information on the feedback features and what is shaping the feedback output.

AWE's common use of occluded terms extends to descriptions of the coding processes, including the use of the industry term "Natural Language Processing," which functions as undefined jargon and uses the technical illiteracy of AWE's users to limit their understanding of what they are getting from the program. Talking around what NLP actually is and how they are utilizing it allows the AWE to situate itself as innovative. Criterion, PWA, and Grammarly all specify that their programs use "Natural Language Processing," but do not provide detail about the type of NLP used or the databases used as sample input. For example, ETS offers an about page for their e-rater scoring engine, which is used for a number of ETS programs, including Criterion. They note that the e-rater system "uses AI technology and Natural Language Processing (NLP) to evaluate the writing proficiency of student essays by providing automatic scoring and feedback" (https://www.ets.org/erater/about.html). When users click on the "how it works" tab of the page, they are informed that the engine builds on "nearly 2 decades of Natural Language Processing research at ETS," but there is no clarification of what those two decades of research entail, what NLP actually is, or how their version was developed (https://www.ets.org/erater/how.html). They provide enough information to give the appearance of transparency, but the information provided does not explain the way the NLP is used or developed. They trust that the reader likely will not know enough about NLP to ask those questions, relying on jargon to keep people situated in a place of technical illiteracy without even realizing their situation. This can be seen as a form of manipulation for users to buy into the service because the AWE is presented as having innovative, extraordinary capabilities through the framing of the term "Natural Language Processing." That is not to say these programs are not innovative or extraordinary, simply that NLP can be an occluded term for individuals without a technical coding background.

Discussion Point 2: User design and circuitous website navigation is used to black-box user understandings of AWE. Writing suggestions are circular in their explanations.

This question of black-boxing also ties back into the rhetorical choices made by the program. The use of jargon is not accidental, it is an active rhetorical choice. This is especially clear when considering that many of the programs did provide descriptions of their assessment categories, but the descriptions were often not helpful in understanding what the program was actually looking for.

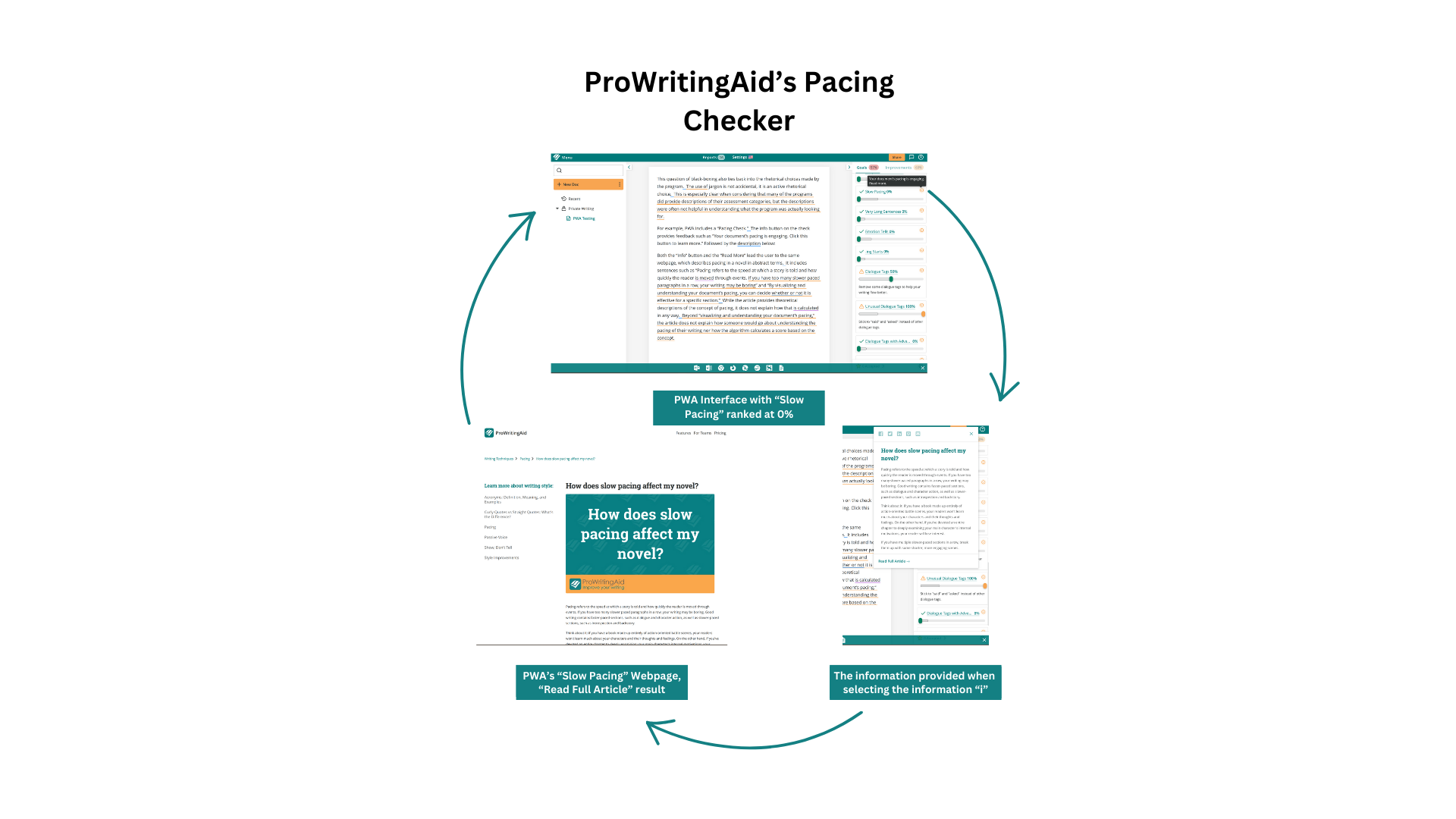

For example, PWA includes a "Pacing Check." The info button on the check provides feedback such as "Your document's pacing is engaging. Click this button to learn more." Followed by the description below:

"Pacing refers to the speed at which a story is told and how quickly the reader is moved through events. If you have too many slower paced paragraphs in a row, your writing may be boring. Good writing contains faster-paced sections, such as dialogue and character action, as well as slower-paced sections, such as introspection and backstory. Read More > (Pacing)

Both the "Info" button and the "Read More" lead the user to the same webpage, which describes pacing in a novel in abstract terms (see image 3). It includes sentences such as "Pacing refers to the speed at which a story is told and how quickly the reader is moved through events. If you have too many slower paced paragraphs in a row, your writing may be boring" and "By visualizing and understanding your document's pacing, you can decide whether or not it is effective for a specific section." While the article provides theoretical descriptions of the concept of pacing, it does not explain how that is calculated in any way. Beyond "visualizing and understanding your document's pacing," the article does not explain how someone would go about understanding the pacing of their writing nor how the algorithm calculates a score based on the concept.

Connected to this is the inconsistency of the use of certain terms across programs, including the concept of "Consistency," which was used by some programs in very similar ways. As we described in our findings section, VWT, PWA, and Grammarly all used the concept differently. They did not use the same measurement to address the concept. Notably, in the case of PWA, they provide various "Consistency" checks, but unlike many of their other checks, they provide no description or explanation for what the check is looking for or what "Consistency" means in this context. This inconsistency prevents users from even getting a sense of what their feedback means or how the algorithm functions, even in the case of terms that appear across programs.

Discussion Point 3: Black-boxing occurs through appeals to current-traditional rhetoric and static abstractions

The inconsistency in the use of certain terms is partially related to AWE's general use of static abstractions. The term static abstraction refers to the words or phrases intended to provide feedback on styles of writing which become abstracted such that their specific meaning is unclear (Connors, 1997, p. 269). Traditionally, static abstractions would include terms such as clearness or unity, which may invoke the feeling of a specific meaning, but cannot really be quantified or explained in practical terms. We suggest AWE run on static abstractions: "Cohesion" is a static abstraction, and as a result, it is not defined or used consistently across programs. Other static abstractions that appeared frequently include "Word Choice/Vocab," "Fluency," "Formality Level," and "Tone."

Additionally, through their use of static abstractions and their lack of explanatory materials or tutorials, the programmers are engaging with an ableist ideology of ease. They approach their programs with the idea that all users will engage with the program in specific, narrow ways. In doing so, they are making narrow assumptions about their audience, which could make their product inaccessible to some users. And beyond the question of if it is accessible once in use, the companies are also assuming that users will come to these programs with specific experiences and knowledge and will be able to figure out how to use the program in the first place. The black-boxing that these companies do, means that they do not have a lot of explanatory material guiding users through the program. To assume that everyone will come to the program knowing how to engage and interested in that specific form of engagement is rooted in ableist ideas of a uniform human experience. Ultimately, our analysis of the features that are assessed by the AWE are typically focused on upholding and perpetuating proponents of current traditional rhetoric (CTR) as defined by Berlin (1980). These CTR components predominantly emphasize sentence structure, syntax, spelling, punctuation, and style. The eight AWE and their features directly reflect these concerns if we look at the features that most of them had in common: "Grammar," "Spell Check," "Punctuation," "Word Choice," and "Cohesion." Even the features that were not common amongst the majority of AWE still highlight a focus on current traditional rhetoric: "Sentence Length/Variance," "Organization," "Formality Level," "Clarity," and "Fluency." These concerns about CTR's focus on effective written communication can be seen in studies that focused on uncovering if AWE can assist students with improving their grammar (Laio, 2016; O'Neill & Russell, 2019; Lee, 2020). In these studies, they found that their AWE under investigation can help students improve their grammar, further highlighting the primary utility of AWE—to assert CTR as its primary function. We can also infer that this is the focus due to the "basic assumption about how natural language works, namely, that language is linear on the surface and this linearity is determined by grammar. Thus, if researchers could construct all the rules that dictate how 'elements in well-formed sentences' may be combined, then in principle those rules may be translated into the artificial language of computers" (Ericsson & Haswell, 2006). The majority of these programs are not concerned with (and potentially not capable of addressing) the intellectual content of the writing it is assessing. They do not provide feedback on how to develop one's ideas or if an idea is logically sound. These algorithms provide feedback based on a set of rules and choices that the programmers have selected. The feedback has to be centered on linearity of sentence structure.

Therefore, because writing is a "socially embedded process," we would "question the ability of AWE software to judge critical thinking, rhetorical knowledge, creativity, or a student's ability to tailor their text to a specific readership" (Hockly, 2019). Appealing to different audiences requires an understanding of the complex web of conventions that are not beholden just towards the way something is written. The AWE that claim to assess audience are pigeonholing genre to distinct word choices and linear constructions of phrases, instead of content. In this way, genres become rigid and one-to-one relations that ignore the fluidity of typified occurrences. Because linearity is the primary capability of AWE, it is more suited to assess structures of writing that closely align with CTR outcomes. Higher level writing concerns, such as "Ideas," "Extraneous Information," and "Organization," are primarily available if the individual subscribes to a paid tier of the AWE. These higher-level concerns supposedly may assist in helping the individual with components of writing that move beyond just sentence structure, such as: argument strength, extraneous information, thesis, and attention to audience. The features that are free are aligned with concerns of CTR.

It is worth noting how CTR features are abundant across multiple AWE we analyzed, while "higher level" writing concerns are not. Speculatively, this too calls into question the capability of these features if multiple AWE do not see these as common concerns for writers. Questions arise from these observations: Are programmers reifying CTR? Are they merely reflecting writing assessment trends in the classroom? Is there another cause of this trend? Whatever the reason, the outcome remains the same, the intention of these AWE is black-boxed, obfuscated, and occluded.

Limitations to the study

The sample size of the AWE analyzed is not exhaustive, therefore, statistical issues exist in our claims. However, this was not meant to be an exhaustive study of all AWE; it was intended to be a preliminary study to gather insight of potential intersections for research. Due to the small sample size, the data is only based on these specific AWE that were selected by three researchers. In this, there potentially lies implicit bias as no unifying strategy was developed for the selection process of the AWE. It should also be considered that this data was gathered in Fall 2021, prior to the release of ChatGPT and the increased use of Generative AI incorporated into AWE and word processing technologies. An initial review of the data in Summer 2023 shows that there seemed to be few significant changes in the services provided by the AWE studied. However, this was a cursory review and further research on the impacts of Generative AI on these programs should be conducted.

Additionally, this was not a funded study, so the paywalled AWE prohibited us from testing certain features or interacting with the AWE interfaces. Specifically, we were unable to use Criterion, WriteToLearn, and MI Write in any capacity since they were completely paywalled. Therefore, any claims asserted or data gathered from these three AWE were based on information provided on their home websites.