Rhetorical Information Theory

Patrick Love

Rhetorical DIKW

A rhetorical approach to DIKW suitable for active learning and process-pedagogy should emphasize the rhetorical principles of evaluating ecologies and experiences to facilitate decision-making, active engagement, and the promotion of mobility and equity (Aristotle, 2007; Edbauer, 2005; Hinks, 1940). Since evidence disconnected from human experience can be gathered unethically or become technocratically oppressive, rhetoric values both evidence and experiences (Hinks, 1940; Katz, 1992). Therefore, a rhetorical interpretation of DIKW should emphasize the rhetorical effort required to transform one level into another rather than just how to move content. Rhetorical DIKW is also informed by circulation theory, particularly 1) in treating data, information, knowledge, and wisdom as ways of understanding the world at different places and times, with different levels of durability and 2) adopting an explicitly future-oriented approach to knowledge creation: wisdom should be regarded as an ecological impact that writers benefit from envisioning while working. Rhetorical DIKW intends to connect lived experiences and external evidence through actively cultivating one's own perspective on the world and fitting it into a larger, collective understanding through active participation in its direction and evolution. The following definitions and discussions should inspire instructors to see this work in their existing practices as well as experiment with new ones that engage the metalanguage productively and critically.

Data

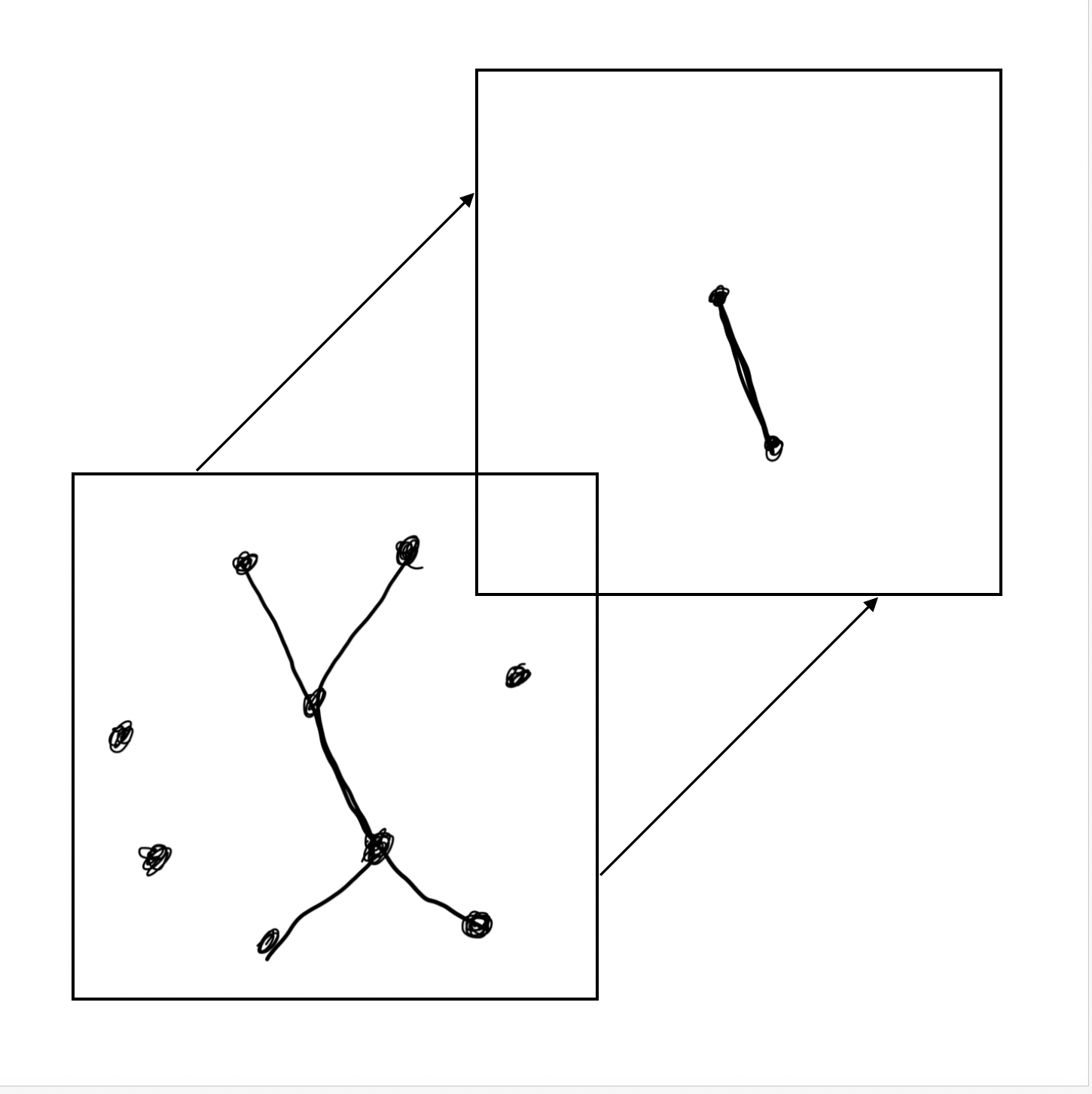

Data can, simply, be whatever precedes information; data is points of observation or measurement before they are connected to have meaning beyond those points. Kelleher and Tierney aggregate definitions of data across the information and scientific tradition into data as “abstractions of real-world entities (variable, features, attributes)—not the thing observed itself but a record of the thing” (2018, p. 39). Kitchin highlights purposeful abstraction as the key transformation that produces data (Figure 1): data spatiotemporally abstracts the world—selectively cutting something from its time and place—via a capture method (note-taking, photographing, digital duplication, etc.) to try to (re)construct information on the relationships between the observations. Salvo (2004) identifies data as the product of analysis, and Buckland (1991) describes data as collected records available for processing, in either a virtual or physical place. Therefore, a rhetorical definition of data should emphasize the purposeful transformation that occurs when data is collected, acknowledging the imperfection of abstracting and isolating something from the world/life when it is added to a dataset seeking to represent "lived" reality.

Data: purposefully collected measurements of the world (stored or recorded as measurements, either quantifiable or qualitative)

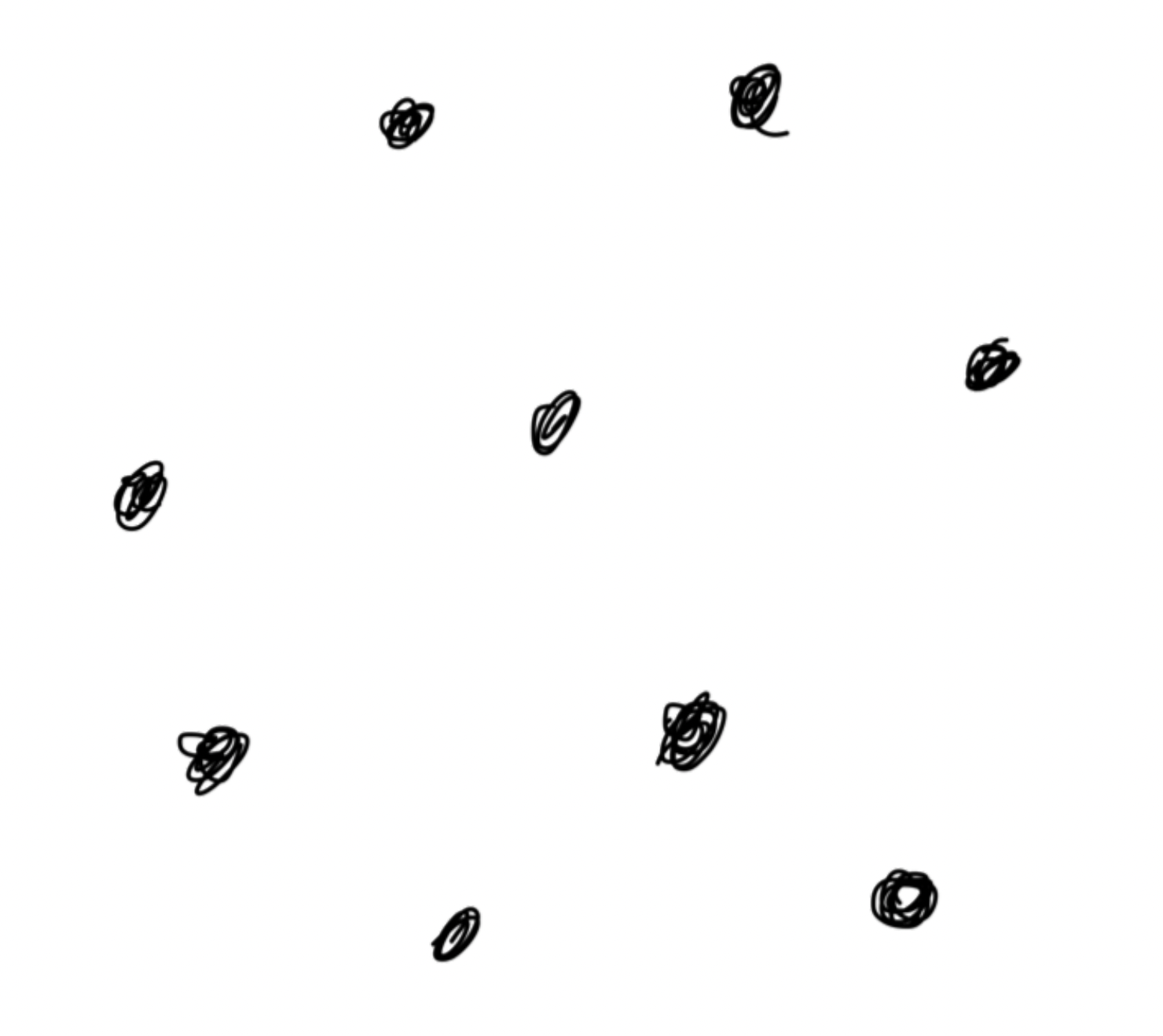

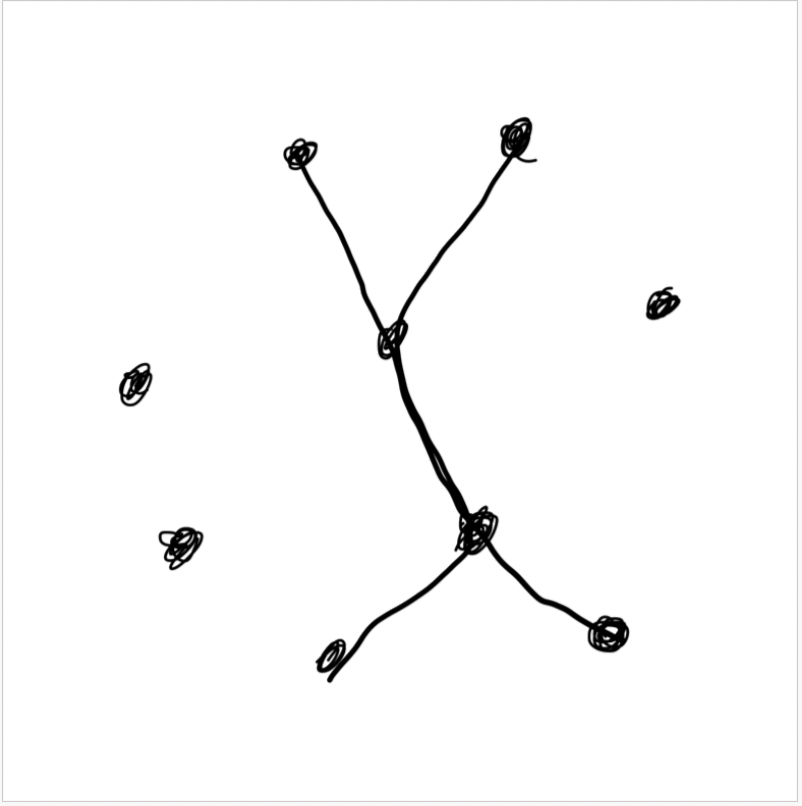

Data, as a practice of representing the world, may be thought of as using one’s experiences to locate and place dots on a map, as in figure 2.

Information

Rhetorically describing information must account for how a document (article, essay, post, video, media of any kind) is information when one reads it to entertain a new idea and how the same document becomes rhetorical data when combined with other sources to make a new piece of information (a narrative proposing a new idea/pattern). The Latin and Greek origins of information (informatio, morphe, or plērophoria) connote giving form to ideas to convey them to someone (i.e. design) (Buckland, 1991), and information-as-quantified-intelligence refers to bits assembled into a digital document (files, posts, etc.) for circulation, so information distinguishes itself through genre and the way one encounters it: as a document or narrative to an audience (Buckland, 2017). Data may possess the possibility "to inform," but it requires processing first; “raw data” is a misnomer, but to say a dataset “informs” without processing labor is disingenuous. Rhetorically, information is data transformed into a meaningful string/pattern/narrative, and data is a prospective component one may combine with others to produce information.

Information: data organized to make meaning (i.e. "pattern-making" and narrative over "quantifying intelligence" or producing "usable units")

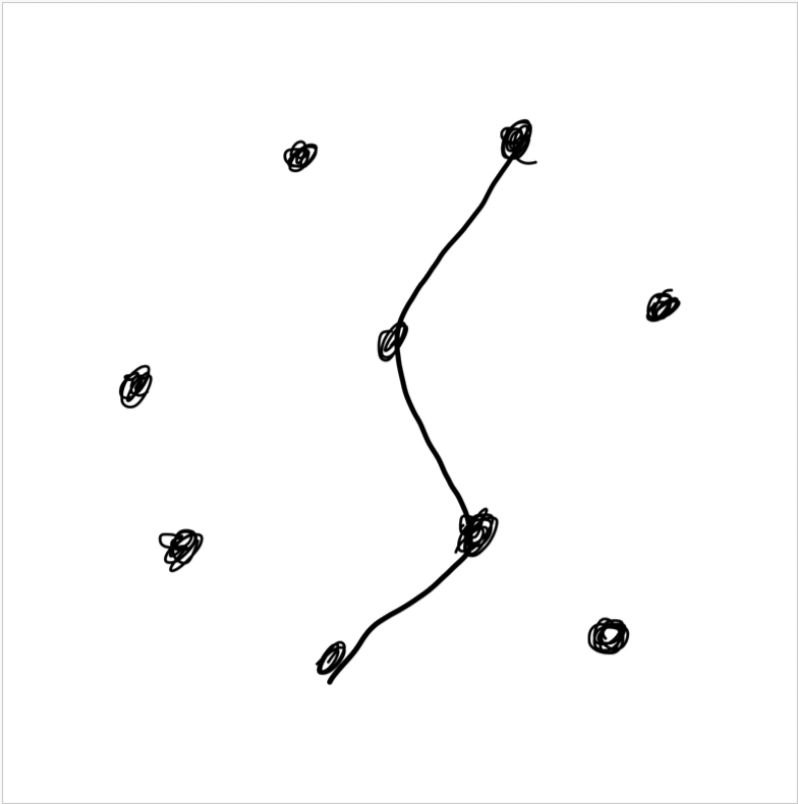

Information, as a practice of making meaning from specific points, may be thought of as connecting the located dots into a strand of meaning, as in Figure 3.

Knowledge

Knowledge is the point where information transforms from a legible pattern representing the world (something believable) into a way to understand the world (belief). Existence in the world is social, so knowledge implies a social, shared belief in some information, imparting a capacity to affect how one views existence (as part of the world). Information known by one person is a belief; knowledge is belief shared with others—something beyond information duplicated in a network (Buckland, 1991; Gleick, 2011). Kelleher and Tierney aggregate knowledge definitions for industrial Data Science as "information structured to be understood or applied" (2018, p. 56). Knowledge, therefore, has to be information multiple people share an experience of, through belief or other social agreement (citation of secondary accounts, etc.), enabling them to view the world a certain way together.

Knowledge-making invokes concern for futurity and power whether or not we explicitly acknowledge it. Foucault argues that Enlightenment moving truth (via knowledge) from the domain of monarchs (primacy of one person's beliefs) to the domain of (more) people made it social (Foucault, 1984; Foucault, 1975; Foucault, 1978). Buckland (1991) differentiates information from knowledge as an idea that is solely the possession of one person's mind, like a belief or opinion (pp. 351–352). Therefore, information rhetorically transforms into knowledge when multiple people can rely on and defend it because they find it legible and in alignment with information or other knowledge they already possess (i.e., not the same as information replicated in a network) (Gleick, 2011). Citation and peer review, for example, signify that given information aligns with other experiences and is worth circulating for consideration as knowledge. Building communities around practices of citation and circulation to produce knowledge is part of institutionalization, but institutionalization is not a requirement of knowledge-making; all that is required is two or more people believing and validating the same piece of information. Composition and Professional and Technical Communication (PTC) are integral to circulating information as part of argument and decision-making, whether through researching and synthesizing arguments about life and the world, document and interface design, or through theories of audience and the systems that shape data collection, pattern-making, and experience-sharing. The labor of knowledge-making, therefore, makes for a reasonable organizing concept for composition classes because it 1) accounts for disciplinary concerns of Rhetoric and Composition and PTC while 2) invoking empirical and active learning principles and 3) teaching institutional and industrial skills one needs to know to make the best use of information technologies (like generative AI) in any discipline (i.e. what is knowledge and how do we make and preserve it).

Knowledge: shared worldview based on a common experience of some information, through communication or application, by multiple people

Knowledge, as a shared experience of information forming joint belief, may be thought of as information strands overlapping and binding together into social bonds, as in Figure 4.

Wisdom

Wisdom is the completed feedback loop of knowledge-making wherein people apply, practice, or embody knowledge by reflecting the worldview they share with others through actions, exercising the social validation they feel from a community (institution, local, distributed, etc.). Wisdom invokes futurity in DIKW and implies ethics, making it an ideological minefield. Kelleher and Tierney aggregate wisdom definitions into, succinctly, "knowledge applied appropriately" (2018, p. 56). Wisdom is where data-driven fields like Data Science acknowledge their role in shaping the future beyond wrangling data into usable, informative units. The appeal of fields like Generative AI and Data Science that rely on large datasets, high-performance computing, and novel applications, is that they present wisdom (the future-tense) as a data-driven product more efficiently produced with machines (Kelleher & Tierney, 2018; Zuboff, 2019). Bluntly, industrialized data industries use empiricism to argue the future can be planned, so the next questions are "by and for whom?"

Wisdom, in other words, has to do with the why of knowledge-production: what ends and material, ecological, and social effects knowledge-work should pursue. This open-endedness confirms the rhetoricity of previous levels: the nature of the data and the form and meaning of the information experienced effect the knowledge underpinning wisdom. Traditional DIKW apolitically side-steps this question because it is borne out of an engineering and scientific tradition of figuring out how to efficiently transfer information and enable vast and various forms of information to exist simultaneously (Gleick, 2011). One might think of traditional DIKW solving a logistical problem of how to create and move knowledge with machines so the content of that information/knowledge can be interpreted by specialists. Rhetorical DIKW, therefore, takes up a humanist perspective by consciously considering and analyzing the process of thought becoming action/wisdom. Because rhetoric deals with decisions, mobility, and ecological consequences, this chapter proposes future-oriented democracy, justice, and survival as the rhetorical-ethical metrics on which to evaluate wisdom transformed from knowledge.

Survival means having a tangible future, as in the ability to both imagine a future and live into it (Kohn, 2013). Inability to imagine a future can empirically indicate insecurity and unsafety, something debilitating or traumatic depending on how long it lasts. Technocratic DIKW, for example, produces a privately-owned certainty of the future that is anti-rhetorical because it is not public/democratic (Zuboff, 2019; Johnson, Salvo, & Zoetewey, 2007). Democracy and justice refer to tireless and rigorous actualization of symmetry in people's relationships and participation and governance by identifying the greatest power asymmetries and applying appropriate asymmetrical responses to remedy them (Crenshaw, 1989). Survival, justice, and democracy ultimately deal with human-made institutions, power, and the nature of humans-in-the-world (Kohn, 2013) coming about through planning and cooperation. Rhetorically presenting DIKW can illustrate for students that cooperation with machines always has human results that we have to consciously craft, with or without machines.

Wisdom: future-oriented application of knowledge promoting democracy, justice, and survival

Wisdom, as action based on a shared worldview, may be thought of as people's knowledge strands set on a three-dimensional plane spatiotemporally persisting to form a feature of the world, or at least a new map of it, as in figure 5.