Composing New Urban Futures with AI

Jamie Littlefield

Three AI-Generated Examples of Speculative Design

To examine the potential uses of speculative design in text-to-image synthesis, I will consider three generative examples. Each of these small, exploratory projects turns a critical eye on the work I've conducted in the area of human-scale, eco-friendly city development as a non-profit communications consultant. These synthetic images are not intended to be polished pieces; instead, they are examples of tactical communicative interventions that can be rapidly created by underresourced groups.

Generative Example #1: Tracing the Projected Past

This first project demonstrates the ways that AI text-to-image synthesis re-creates the conventions of the past and provides suggestions for interventions based on speculative design. To begin this project, I examined how generative AI uses the cities of the past to create new images. Over 14 consecutive days, I entered the same three-word prompt in Midjourney's image-generating Discord server:

ideal neighborhood. photorealistic.

Out of the four resulting image options from each of the 14 initial generations, I consistently upgraded the first image (on the top left of the image results). I archived these synthetic images and analyzed the results, as shown in Video 1. By using the same prompt, I was able to develop a small corpus of synthetic images. Rather than analyzing images individually, examining a collection enabled me to begin identifying patterns.

Users may be tempted to assume that the resulting synthetic images would be widely varied, considering Midjourney's extensive training datasets. "Neighborhoods'' have long existed in a wide variety of countries, cultures, and decades. "Ideal" is similarly a vague descriptor that could apply to many subjective contexts. However, in this experiment, Midjourney recreated many of the same details for the prompt in different configurations. Its "new" output reflected patterns from particular subsets of the past.

Descriptive Video Transcript

| Onscreen Text | Image Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Tracing the Past with AI

Asking AI text-to-image synthesizer Midjourney to generate a new image every day for the prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic" | ||

| Day 01 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A residential street lined with two- and three-story houses featuring classic architectural details such as bay windows, front porches, and decorative trim. The houses are painted in muted greens, blues, and reds. Trees with autumn-colored leaves line both sides of the street, casting shadows on the pavement. The asphalt street has concrete sidewalks directly alongside it, with steps leading up to the houses. A single car is visible in the distance. The sky is blue with scattered clouds. | |

| Day 02 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A picturesque residential street lined with colorful Victorian-style houses, featuring ornate trim, bay windows, and decorative railings. The houses are painted in deep blues, greens, and reds, with lush landscaping spilling onto the sidewalks. Trees with vibrant autumn leaves create a canopy over the street. The asphalt road is narrow, with a few cars parked along the curb. Sunlight filters through the trees, casting golden light and long shadows. Overhead power lines run diagonally across the sky. The street gently curves in the background, leading to more houses and trees. | |

| Day 03 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A residential street lined with two-story houses featuring pitched roofs, front porches, and wooden siding. The houses are painted in muted greens, blues, and tans. The street is paved with asphalt, with concrete sidewalks separated by narrow grassy strips. Cars are parked along the curb. The sky is golden, suggesting early morning or late afternoon. | |

| Day 04 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A tree-lined residential street with large, two- and three-story houses featuring pitched roofs, front porches, and decorative trim. The houses are painted in shades of green, brown, and navy blue. The street has grassy front yards, concrete sidewalks, and cars parked along the curb. Shadows from tall, mature trees create a dappled effect on the road. The background shows more houses and trees. The sky is blue with wispy clouds. | |

| Day 05 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A suburban residential street with two-story houses featuring pitched roofs, front porches, and decorative trim. The houses are painted in soft blues, greens, and yellows, with well-maintained landscaping. A red car is parked along the curb, and a few people are walking on the sidewalks. A group is gathered near a house. Trees with green and autumn-colored leaves cast dappled shadows. The sky is bright blue with scattered white clouds, and a small airplane is visible. | |

| Day 06 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A tree-lined residential street with two-story houses painted blue, green, and brown. The street is paved with asphalt, with concrete sidewalks and grassy front yards. Trees with green and red foliage cast shadows. Cars are parked along the curb, and a few vehicles are driving down the street. Sunlight filters through the branches, creating a warm glow. The background shows the road continuing into the distance. | |

| Day 07 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A residential street at dusk, lined with two-story houses painted deep green, red, and blue. The street is paved with asphalt, with concrete sidewalks and grassy front yards. Streetlights cast a warm glow, illuminating the sidewalks and parked cars. A few cars drive down the street, their taillights glowing. Birds fly overhead against a golden-orange sky with scattered clouds. Trees with dense foliage partially frame the scene. | |

| Day 08 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A row of closely spaced, two- and three-story houses painted green, blue, and tan. Each house has a small front yard with neatly trimmed grass. The asphalt street has concrete sidewalks. A few cars are parked, and one vehicle drives down the street. Overhead power lines run diagonally. Trees with green and red autumn foliage cast shadows. The warm sunlight suggests early morning or late afternoon. | |

| Day 09 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A residential street lined with two-story houses painted navy blue, beige, and light brown. Each house has well-maintained yards with flower beds. The asphalt street has concrete sidewalks and grassy front yards. A red car is parked along the curb. Power lines and wooden utility poles run along the street. The golden sunlight suggests late afternoon or early evening. The sky is blue with wispy clouds. | |

| Day 10 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A quiet residential street lined with modest two-story houses painted beige, red, and green. The street is paved with asphalt, with concrete sidewalks. Several cars are parked, including a blue sedan. Overhead power lines stretch down the street. Trees with golden leaves cast dappled shadows. The sky is bright blue with white clouds. The background shows the street continuing into the distance. | |

| Day 11 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A residential street with two-story houses painted navy blue, beige, and brown. Each home has flower beds and hedges. The street is paved with asphalt and lined with trees casting dappled shadows. Power lines and wooden poles extend along the street. The warm sunlight suggests late afternoon or early evening. The background shows more houses and trees. | |

| Day 12 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A street lined with tall, Victorian-style houses painted green, beige, and blue. The asphalt street has concrete sidewalks. Trees with red and golden autumn leaves arch over the street, casting shadows. Several cars are parked, including a red car. Overhead power lines crisscross above. The street continues into the distance, framed by houses and trees under a bright blue sky. | |

| Day 13 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A tree-lined street with Victorian-style houses painted red, beige, and blue. The street is paved with asphalt and has concrete sidewalks. Cars are parked along the curb, including a red car driving down the street. Trees provide shade, casting shadows. The sky is bright blue with fluffy white clouds. The street extends into the distance, lined with more houses and trees. | |

| Day 14 Midjourney Prompt: "/imagine: an ideal neighborhood. photorealistic." | A vibrant residential street with colorful Victorian-style houses painted red, orange, blue, and green. Trees with golden leaves line the street. Some cars are parked and some cars are driving. Overhead power lines crisscross above. A modern city skyline with skyscrapers rises in the background. The sky is bright blue with scattered clouds. | |

| Audio Note: This video contains no spoken dialogue. The background track features calm, upbeat music with a synthetic quality, resembling piano sounds. | ||

After compiling these synthetic images, I examined the threads that connected them. I found that Midjourney was projecting a very specific interpretation of “ideal” and “neighborhood.” The corpus of synthetic images tended towards:

- Suburbanism. All of the images showed houses in suburban settings. There are no mixed-use options (i.e., combinations of different types of building uses such as commercial spaces, apartments. or local restaurants). Only one image displayed an urban area in the background.

- Americanism. Although the specific locale is unclear, the general aesthetics of the streets suggest that they are located in the United States (or possibly Canada). The architecture appears to be Victorian or Edwardian, a style popular in the U.S. from the late 1800s to the early 1900s and characterized by integrated details, varied rooflines, bay windows, and ornamental trims.

- Car-centricity. 100% of the synthetic images include cars using the public space in the street or sidewalk. By contrast, only 7% of the images included humans using these public spaces. No alternative transportation methods, such as light rail, scooters, or buses were identified. Additionally, only 42% of the synthetic images included usable sidewalks on both sides of the street (or one side if only one side was pictured) that would be unobstructed to a person using a wheelchair or pushing a stroller.

- Classism. All synthetic images featured large houses (generally two or three stories) in good condition with front porches and mature trees in what could be considered historic areas.

- Racial Exclusivity and Redlining. While the images do not explicitly depict people, they evoke the aesthetics of redlined communities and mid-20th-century suburban idealism. The visual elements—large homes, manicured lawns, and detached housing—align with the historical American Dream imagery that was explicitly marketed to white, middle-class families in the post-WWII era. The federal government’s redlining policies and exclusionary zoning laws contributed to the development of these suburban enclaves, shaping neighborhood access based on race and economic status. AI’s reliance on past datasets means that it unintentionally perpetuates these historical patterns, reinforcing a limited and exclusionary vision of what an "ideal neighborhood" should be.

By drawing out the patterns in these images, we can start to identify how the AI text-to-image synthesizer is replicating a certain interpretation of the past. We can also begin to imagine how using these synthesized images in communicative contexts could produce value-lock by limiting the way we think about the future of neighborhoods. From the position of my own grassroots advocacy, I am concerned that using these images might contribute to the replication of the same type of exclusionary spaces that are already present in the built environment.

Applying a speculative design approach can help users imagine alternative ways to think about the same concept. Speculative design asks us to consider what alternative futures might be available to us. What if we were to create and circulate images of ideal neighborhoods that were not suburban, American, car-centric, and upper-class? What other types of neighborhoods might be considered "ideal" in the future? Speculative design practices can help users imagine built environments that are less predictable and less inclined to perpetuate value-lock.

One approach to generating more speculative synthetic images is to use AI as a tool for what Deleuze and Guattari (2013) call "rhizomatic thinking." Rhizomatic thinking is a non-hierarchical, decentralized cognitive approach that allows for multiple entry and exit points, much like the underground stems of rhizomatic vegetation (like bamboo, ginger, or mint). Unlike traditional, linear ways of thinking that seek a single "correct" solution or approach to an answer, rhizomatic thinking embraces complexity, multiplicity, and interconnectedness. In the context of AI-generated images, this means moving beyond mere replication or simulation of existing visual forms derived from the past. Instead, AI can be prompted to explore a larger array of possibilities, each branching off from the other, to create images that are not just novel but also speculative. These images can challenge our preconceived notions of reality, aesthetics, and even the limitations of human imagination, opening up new avenues for inquiry.

After noticing the patterns that emerged in the first corpus of generated images, I worked to create prompts that challenged text-to-image synthesizers to connect the concept of "neighborhood" to concepts that might be considered more distant and less linear. I experimented with new nodes like "Afrofuturism," "design for women," and "agricultural urbanism." The key phrases used in these prompts were intended to serve as nodes for rhizomatic thinking, asking AI to tap into knowledge systems that were further from its original concept of "neighborhoods."

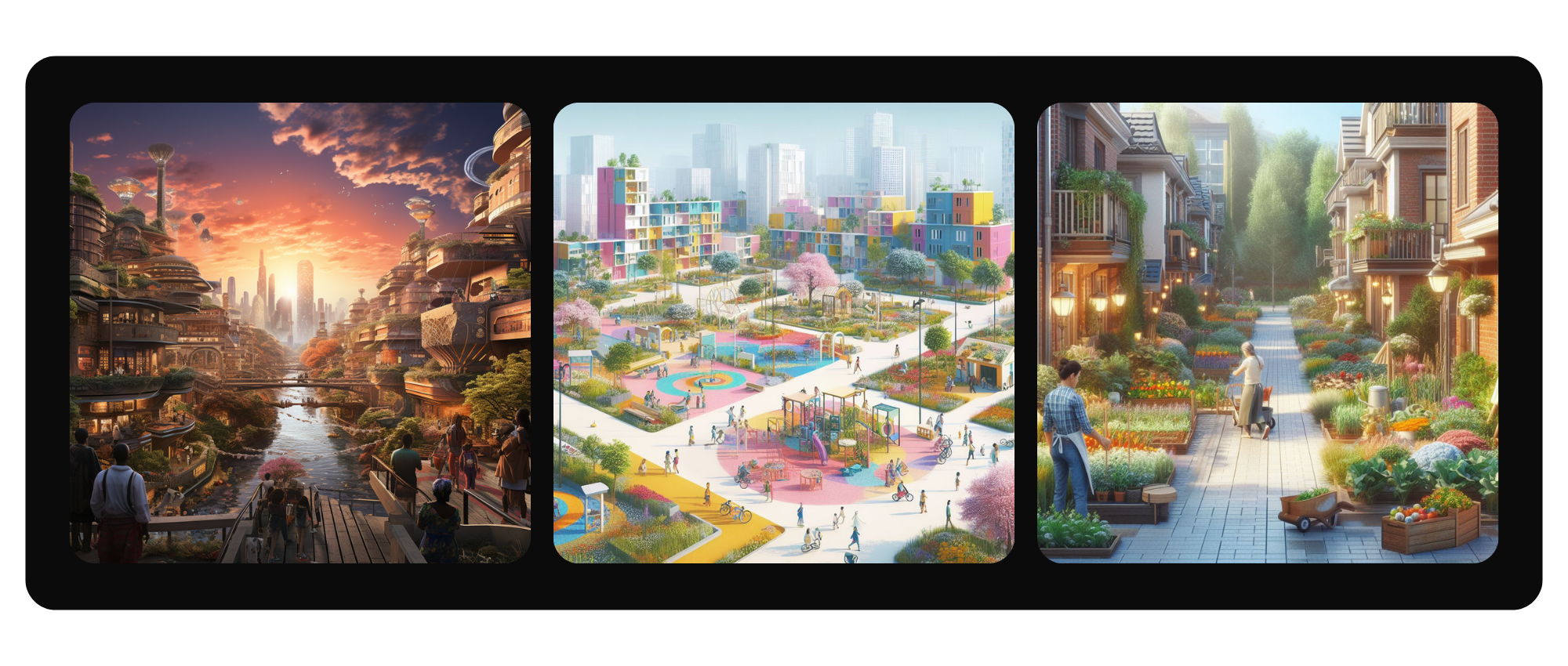

The resulting images (Figure 6) showed visual evidence of meaning drawn from alternative branches of thinking. In these images, we see: neighborhoods being used by many different people, bicyclists and pedestrians, shared public spaces, waterways, communal playgrounds, and different housing types. The synthesizers are still drawing from the past, but the generated content shows greater novelty because it is working with additional units of meaning. It is being asked to create connections between somewhat disparate pasts, between branches of thought that are less related. AI text-to-image synthesis allows users to intentionally and rapidly experiment with this style of rhizomatic thinking by generating content from multiple "nodes" through textual input, providing new possibilities for projecting alternative futures.

While connecting to alternative nodes through rhizomatic thinking helps generate novel combinations, each new conceptual branch carries its own set of value-locked patterns that deserve critical examination. When connecting to "Afrofuturism" as a node, the AI draws from existing visual conventions that often frame Black futures through a lens of technological dystopia and architectural monumentalism, replicating patterns from science fiction media rather than the full spectrum of Afrofuturist thought. The "design for women" node activates deeply embedded visual patterns from historically gendered spaces and marketing, defaulting to stereotypical feminine coding through color and ornamental choices that reflect decades of gender-segregated design practices. Agricultural urbanism visualizations tend to reproduce the aesthetic conventions of contemporary "eco-luxury" developments, pulling from marketing imagery that presents urban farming through a lens of white, middle-class lifestyle rather than connecting to the diverse cultural histories of community agriculture and food sovereignty movements.

| Prompt Node | Description | Prompt Phrases |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Concepts | Foundational elements that anchor the design scenario | Neighborhood, Public space, Urban village, Housing district, City block, Street network, Town square, Transit corridor, Cultural district, Innovation hub, Waterfront development, Mixed-use complex, Educational campus, Healthcare precinct |

| Adjective Modifiers | Qualities that shape the character and atmosphere | Sustainable, Futuristic, Vibrant, Market-driven, Inclusive, Minimalist, Playful, Communal, Resilient, Adaptable, Biophilic, Dynamic, Harmonious, Interactive, Regenerative |

| Styles or Movements | Design philosophies and cultural influences | Bauhaus-inspired, Afrofuturist, Postmodern, Indigenous architecture, Brutalist, Cyberpunk, Art Deco, Metabolist, Solarpunk, Biomimetic, Neo-vernacular, Deconstructivist, Eco-gothic, Retro-futuristic, Feminist, New urbanist |

| Material Features | Physical elements that add functionality and character | Green rooftop gardens, Integrated solar panels, Walkable streets, Community gathering spaces, Vertical farming, Underground transit hubs, Public art installations, Rainwater harvesting systems, Smart street furniture, Urban food forests, Microclimate zones, Elevated pedestrian networks, Wildlife corridors, Energy microgrids |

| Environmental Contexts | Setting and surrounding conditions | Coastal adaptation, Desert oasis, Mountain terrain, Urban forest, River delta, Arctic settlement, Floating city, Underground development, Sky city, Island ecosystem, Canyon dwelling, Wetland integration |

| Social Dynamics | Community interactions and behavioral patterns | Intergenerational living, Creative commons, Learning landscapes, Care networks, Free enterprise zones, Cultural exchange hubs, Maker spaces, Democratic forums, Healing environments, Play zones, Knowledge sharing centers, Ritual spaces, Community kitchens |

These patterns reveal how, even when generating novelty through rhizomatic connections, AI systems reconstruct value-locked elements from each conceptual branch they access. This suggests that speculative design practices must involve not just making new connections between nodes but must critically examine what historical patterns each node brings with it. Practitioners can use this awareness to deliberately identify and challenge these inherited conventions—perhaps by introducing additional nodes that specifically counteract recognized patterns, or by crafting prompts that explicitly reject certain visual tropes. The goal is not only to generate novel combinations, but to thoughtfully curate which elements from each knowledge branch we want to carry forward into our speculative futures.

Composition instructors can guide students through rhizomatic prompt creation by teaching them to strategically combine conceptual nodes (see Table 1). Like assembling blocks of meaning, students can start with a Base Spatial Concept (a "neighborhood" or "public space"), then thoughtfully layer on Adjective Modifiers that shape its character ("sustainable," "vibrant"). By adding a Style or Movement node ("solarpunk," "indigenous architecture"), students begin making more distant conceptual connections. Additional Features ("green rooftops," "community spaces"), Environmental Context ("coastal," "urban forest"), and Social Dynamics ("intergenerational living") can then be mixed in deliberately, with students examining how each new node might introduce its own historical patterns or biases. For example, rather than simply accepting "Design a vibrant neighborhood with indigenous-inspired architecture featuring rooftop gardens in a mountain terrain for intergenerational living," students should interrogate what assumptions about class, culture, and accessibility each element brings. This process teaches critical awareness of how different knowledge branches interact while encouraging experimentation with unconventional combinations that might challenge value-locked futures.

Generative Example #2: Speculative Design as a Tool for Value Negotiation and Identity Formation

As a practice, speculative design challenges communicators to tell stories that prompt discussion about who we are and what we value. By crafting narratives that exist beyond the present moment, communicators invite audiences to confront their own assumptions, biases, and ethical frameworks. This form of storytelling catalyzes dialogue, encouraging people to negotiate their values and reconsider their identities in the face of hypothetical yet plausible situations. In doing so, speculative design transcends aesthetic or functional considerations; it becomes a tool for social critique and identity exploration (Snow et al., 2021).

A place can be understood as a space that is filled with identity, culture, and shared references, bound together in time. Non-places, on the other hand, tend to promote the solitary identity of individuals disconnected from the people immediately around them (Varnelis & Friedberg, 2008). Examining the way places are connected to human values can help us identify what Rai (2016) refers to as "the competing rhetorical frames that circulate within and are tied to literal places" (p. 34).

For this example, I used DALL-E 3 to generate images that promote discussion about shared values around vacant property within my community. This project was done in response to local debate around the need for more convenient parking versus the need for more public spaces.

To generate the first synthetic image, I attempted to create distance between the subject and the anticipated audience. I chose the Eiffel Tower due to its status as a cultural symbol and its physical and ideological distance from Provo, Utah (i.e., it is known and loved but is distant and not considered "ours"). I used DALL-E 3 to generate a synthetic image, removing the public space that picnickers and tourists enjoy below the tower and replacing it with a parking lot for electric vehicles.

For the second synthetic image, I attempted to close the gap between the place pictured and the anticipated audience. Using an iPhone, I took a simple photograph of an empty lot in a downtown Provo neighborhood. I then used DALL-E's outpainting tool to generate three images representing the materialization of different values: the construction of a parking lot, a bicycle-friendly community garden, and a neighborhood restaurant (Figure 8).

The purpose of these generations is not to needlessly provoke but to encourage community discussion. In these examples, I attempted to elicit responses that called for a deeper reflection on the ways public space is used and how that use reflects community values. Speculative design can draw people together around new kinds of inquiry: What do we gain when we use publicly owned space for parking? What do we lose? What does that say about us and our values? Are there specific circumstances where we might choose to trade the convenience of parking for another value, and how do we identify those circumstances?

Generative Example #3: Speculative Design & The Construction of Publics

This final example demonstrates how speculative design has the potential to create publics—groups of strangers who are united around a common text (written, visual, or multimedia). Drawing on the work of Dewey (1927), Habermas (1989), and Latour & Weibel (2005), writing researchers have long been interested in the ways that the creation of a text can construct a group of people and things empowered to take conjoint action (Gries, 2019; Moore, 2023, Preston, 2015; Boyle & Rivers, 2018). Such texts often prompt action through their circulation as a part of a larger rhetorical ecology, generating force through their association with other texts, rhetors, readers, histories, and materials (Rivers & Weber, 2011; Edbauer, 2005). By assembling a public with intentionality, communicators invite readers to see themselves and their involvement in an issue in a particular way and, potentially, work with each other to change the course of the future (Warner, 2002; Rice, 2012).

For this project, I wanted to communicate the urgency of responding to the environmental threats facing Utah due to climate change and highlight the need for alternative transportation methods like infrastructure that supports walking and bicycling. I chose to focus on the Great Salt Lake, a rapidly declining body of water receding due to recent droughts. For generations, the lakebed was used to dispose of toxic chemicals, which now threaten to become airborne as dust storms. I used Midjourney to generate a synthetic image displaying a dystopian possibility for the future of Salt Lake—a dried, cracked lakebed releasing toxins toward the city (Figure 9).

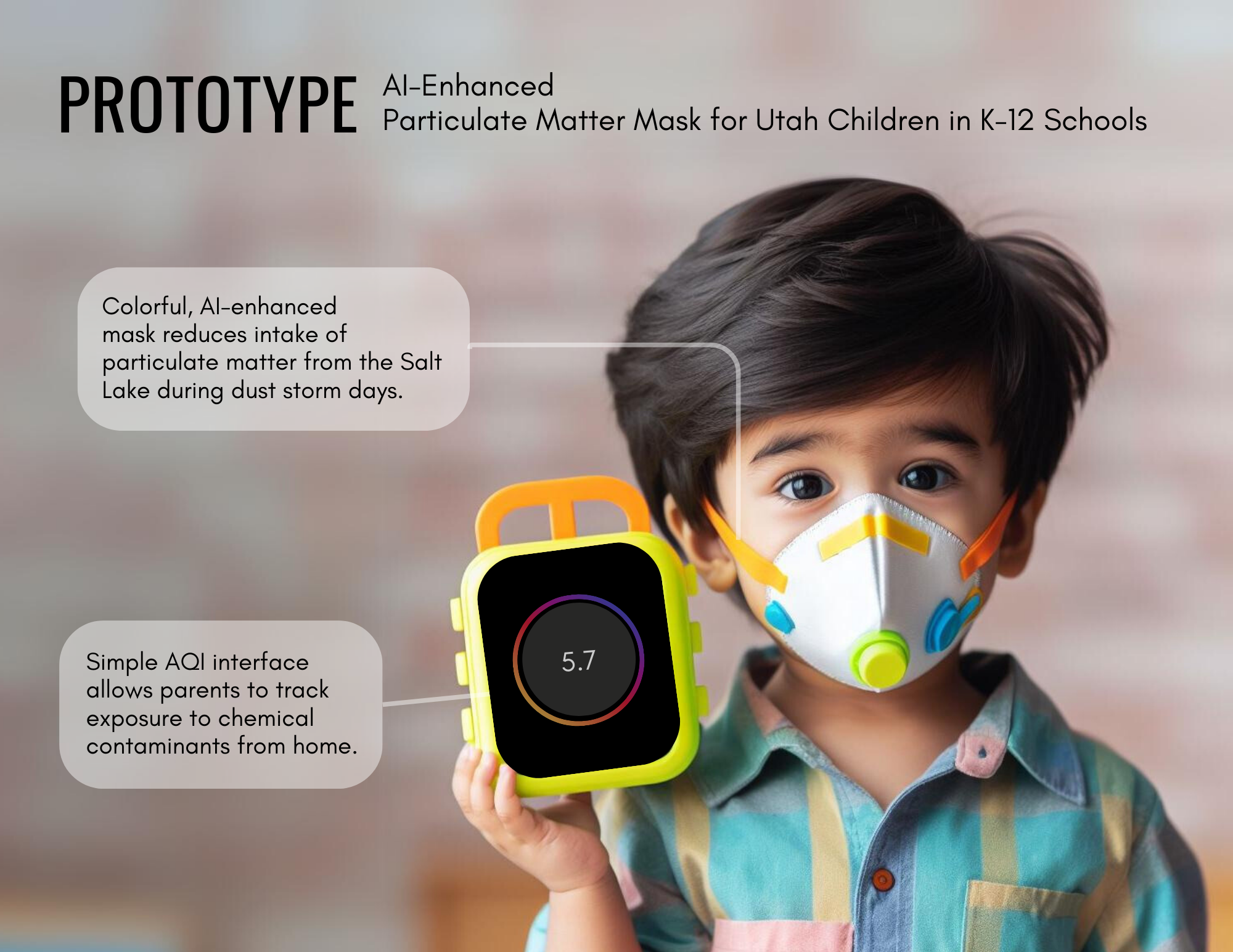

Following the practices of speculative design, I generated a companion image to suggest potential technologies that might be needed to mitigate this dystopian future (Figure 10). Refined in Canva, the image displays a prototype of a colorful mask combined with an AI-enabled air quality sensor that could be distributed to Utah children in areas experiencing toxic dust exposure from the declining lake. While K-12 students in our area are already required to stay indoors during recess on days with dangerous particulate matter readings, such a device could allow children access to outdoor spaces if air quality continues to decrease. These corresponding images invite readers to consider how the actions taken now may impact the nature of our community and the ways we exist within it in the future.

When combined with narrative, speculative imagery can serve as a rhetorical tool to gather the people and materials needed to enact change. In the case above, the images are intended to evoke emotion around an undesirable future and its technological implications and, potentially, generate the affective energy required to initiate public action. Here, again, the purpose is not to needlessly provoke but to identify ways that AI text-to-image synthesis can help us speculate about the future in order to change the present. In this case, generative AI is a valuable tool for rapidly creating narrative-based images and prototypes. It allows users to experiment with variations, pulling together materials of the past to imagine solutions for problems in the future. Most importantly, it offers new tools for communicators to pull together groups of actants around shared concerns.

In my non-profit work, the theories behind the construction of publics have proven particularly relevant. Our task is to assemble groups of people and things (publics) who are inspired to work together to reassemble the material elements of the built environment (streets, bike lanes, parks, etc.). Our recent air quality failures might be viewed as a breakdown in our attempts to effectively form publics—we have not yet been able to assemble the kinds of groups that are capable and motivated to address the environmental problems we face. By providing communicators the chance to rapidly experiment with different types of content creation, we may be able to more effectively assemble the types of publics we need.

It is important to note here that emergent technology may end up impacting not only what publics are formed but how publicness itself is experienced. That is, technology has the potential not only to change the membership of a public but to change the way people/things are drawn into a public and the way they experience that association itself. In Composing Place: Digital Rhetorics for a Mobile World, Greene (2023) points to the ways that technology may be used to create new kinds of public orientations:

Rather than reducing the function of a digital text to its ability (or inability) to persuade a pre-given group of people, we should also attempt to understand how emerging technological infrastructures facilitate new formations of public-ness itself. (p. 40).

As technologies like augmented reality (AR) gain traction, humans may begin experiencing material places (like bus stops or public plazas) through interfaces that restrict or emphasize particular aspects of their experience with the built environment. Wearing AR headsets, one user may see factoids about local art in his visual field, while another may see evidence of local homelessness as a nondescript blur. Such applications function to "not only orient our physical position within a space but also our rhetorical position" (Crider et al., 2020, p. 9). Speculative design offers avenues for drawing users away from their individualized AR experiences and toward shared, material ways of addressing community challenges.