Teaching Knowledge Labor and Literacy for the Age of AI and Beyond with Rhetorical Information Theory

Patrick Love Monmouth University

Introduction

Crypto currency and blockchain architecture, having suffered major public downturns, receded in late 2022 as if making way for mainstream generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) products, replacing decentralized ledgers in public imagination with automatically generated pictures and text via OpenAI’s DALL-E and ChatGPT. An emblematic response was Stephen Marche’s December 2022 article declaring ChatGPT and its underpinning product, GPT-3, the death of the “college essay,” heralding yet another crisis in the humanities, and questioning the value of writing and the humanities in education. Rhetoric and Composition scholars will note the tropes in Marche’s prose implying that writing primarily serves transactional purposes, particularly in academia. Marche’s declaration that the “undergraduate essay” is how “we teach (students) to research, think, and write” is easy enough to get behind, but the point is muddied by a subsequent claim: an unnamed Toronto Associate Professor (presumably of Business) claims that, when writing assignments ask “specific questions that involve combining knowledge across domains,” ChatGPT “is frankly better than the average MBA at this point” (Marche, 2022). Marche’s implied concern is that AI writing can now recreate Knowledge, provided Knowledge is a compelling summary, comparison, or analysis of other writing.

One might understand pedagogical writing and humanities disciplines (like Marche implies) as existing to produce compelling understandings of the present via evidence from the past, placing the future outside its domain (like ChatGPT announcing its data cutoff on startup). This claim is both enabled and undermined by Information Theory, the mathematical basis for constituting knowledge in big-data empiricism: Information Theory translates knowledge-work between human and machine by treating data, information, knowledge, and wisdom1 (abbreviated to DIKW) as both inherently quantifiable and qualitative, requiring rhetorical labor and human sociality to turn one into another. This chapter will examine the tension in Information Theory’s dominant role in empiricism, particularly in digital spheres: treating DIKW as simultaneously quantitative and qualitative incorporates fundamental humanist concerns into knowledge work that an AI, working alone, cannot account for, making human intervention essential. Furthermore, this chapter will present a rhetorically-oriented version of Information Theory’s DIKW Pyramid (Kitchin, 2014), called “Rhetorical DIKW,” that emphasizes the rhetorical relationships and distinctions between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom to help composition instructors 1) teach about GenAI, teach GenAI practices, and bridge between humanist and STEM concerns when teaching about technology and knowledge-work generally and 2) reclaiming DIKW-driven knowledge work as a rhetorical process of consciously forging connections between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom by emphasizing outcomes and consequences. This article presents Rhetorical DIKW as a future-oriented and intersectional approach to knowledge-work, but the general advantage of employing DIKW metalanguage in composition classes is that it promotes a consciously future-oriented approach to "making" knowledge and "doing" wisdom by emphasizing the participatory, rhetorical processes that turn data (observations) into information (pattern) and knowledge (shared perspective) and wisdom (action). DIKW is a fundamentally apolitical framework, so rhetorical DIKW empowers students to see how it produces the future, including the option to make our future sustainable, just, and pleasant to inhabit, something worthwhile with or without GenAI.

Time, Writing, and DIKW

Implicit in Marche’s essay about how ChatGPT fundamentally disrupts college writing is that writing to learn is primary past- and present-oriented, in that it serves to help teachers see how students think about or understand established concepts. In his 1985 article "The Language of Exclusion," Mike Rose explores what he terms the "myth of transience." This myth suggests that either the past was better than the present or that the future inevitably will be, persuading us to ignore ongoing issues or adapt to them with temporary measures. This perspective aligns with a conservative mindset, assuming that the past was idyllic and that fundamentally challenging societal principles in the present is impossible or unnecessary (Rose, 1985, p. 600).

The myth widens the gap between the present and the future while idealizing the past. Rose argues this perspective contributes to the perpetual crises in education and writing instruction by preventing educators from seeing new ways to integrate writing into their classes and research because the future is stochastic (neither random nor predictable) (Rose, 1985, p. 602). The effect traps society in extended focus on "the present" at the expense of "the future." This disconnect echoes Paulo Freire's critique of banking education in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970). Banking education teaches students to accept the world as it is rather than understanding it as an ongoing process they actively participate in (pp. 75–76).

Both Rose and Freire highlight how traditional education often emphasizes knowledge and information at the expense of action and engagement, echoing Socratic belief in dispassionate pursuit of knowledge as a prerequisite of action, further codified during the Enlightenment with empiricism and the scientific method (Cooper, 1997; Locke, 1689; Bacon, 1605). To break free from this passive approach and encourage active participation in the world, Freire suggests "problem-posing" pedagogy, where students collaborate on “cognition, not transferals of information” (1970, p. 79).

The critical distinction between thought/knowledge and transferring information easily muddies, especially in our digital age where transferring information is a big part of practical digital rhetoric. The legacy of Information Theory informs this muddying of practice, but also informs how to distinguish data, information, knowledge, and wisdom, particularly in a world where machines, such as algorithms, Machine Learning, and GenAI, play a significant role in processing data into information and circulating it.

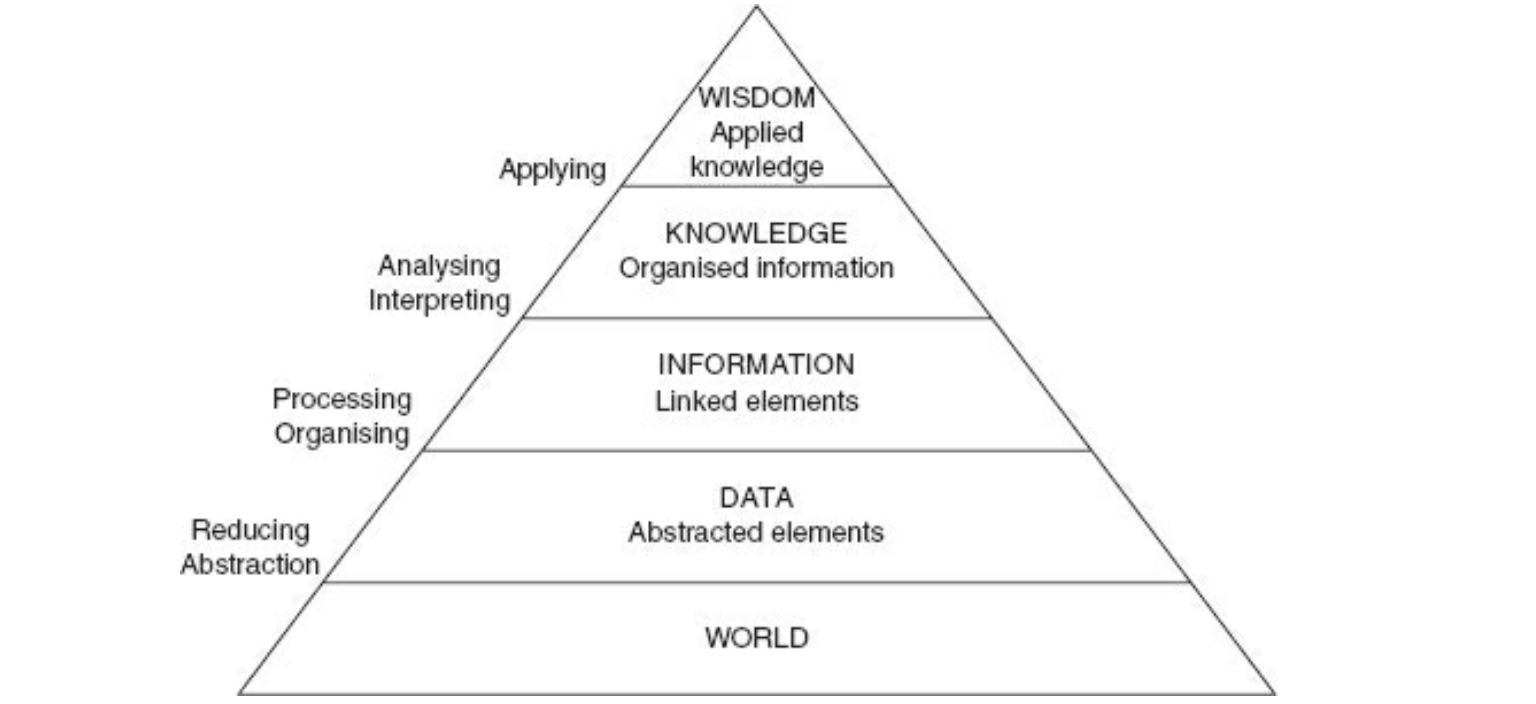

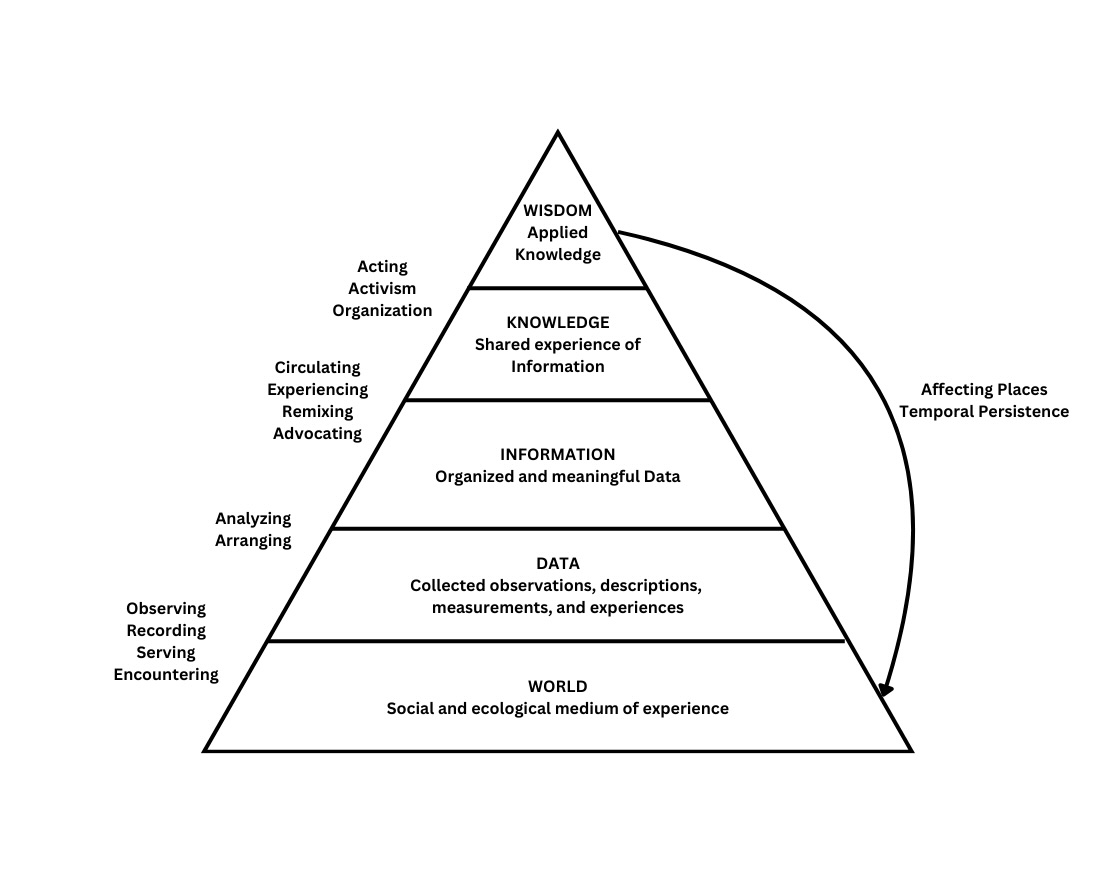

The DIKW Pyramid (figure 1), as a conceptual model of the "levels" of knowledge that humans and machines can both interpret with the most parity (Kitchin, 2014, p. 10), guides Information Theory, Data Science, Machine Learning, and now, as a domain informed by the previous three, LLMs and GenAI development. The pyramid organizes data, information, knowledge, and wisdom into levels, extending from “the world,” with each as a refined reduction of the previous level (Kitchin 2014). The pyramid portrays how we understand the world (as the ecology all activity and places we inhabit) at various levels:

- Data as measurements or observations abstracted (preserved and removed) from the world

- Information as data structured or organized to show meaningful connections between those elements to other humans (or machines)

- Knowledge as information interpreted, analyzed, or understood by multiple people (a shared perspective)

- Wisdom as knowledge applied “appropriately” (having an effect on/becoming part of the world we draw data from) (Kelleher & Tierney, 2018, p. 56).

The move from data to information is analogous to the metaphors of "signal" and "noise": information is another way to refer to "signals" found in noise/data, whether they are intentionally sent or detected in a dataset (or something being treated as data) by a human or a machine (Gleick, 2011; Kelleher & Tierney, 2018). The relationship between data and information is also a rudimentary way to understand language in communication: an alphabet as a dataset that gives rise to patterns (words) that themselves form larger patterns and gain meaning (beyond the letters themselves) based on their relationships to each other in use (Gleick, 2011). The move from data to information is also a good way to understand the “stochastic parroting” (Bender et al., 2021) that LLMs/genAI do when responding to a prompt: LLMs survey their training data and form patterns that seem a likely response or continuation in the pattern they perceive in the user's prompts. By expanding the rhetorical mechanics of this pyramid, we can not only teach it to students as part of information literacy and argumentative writing (and AI literacy, for that matter), but also connect it to process-based composition pedagogy and explore how genAI contributes most effectively to students' writing processes.

Rhetorical DIKW

A rhetorical approach to DIKW suitable for active learning and process-pedagogy should emphasize the rhetorical principles of evaluating ecologies and experiences to facilitate decision-making, active engagement, and the promotion of mobility and equity (Aristotle, 2007; Edbauer, 2005; Hinks, 1940). Since evidence disconnected from human experience can be gathered unethically or become technocratically oppressive, rhetoric values both evidence and experiences (Hinks, 1940; Katz, 1992). Therefore, a rhetorical interpretation of DIKW should emphasize the rhetorical effort required to transform one level into another rather than just how to move content. Rhetorical DIKW is also informed by circulation theory, particularly 1) in treating data, information, knowledge, and wisdom as ways of understanding the world at different places and times, with different levels of durability and 2) adopting an explicitly future-oriented approach to knowledge creation: wisdom should be regarded as an ecological impact that writers benefit from envisioning while working. Rhetorical DIKW intends to connect lived experiences and external evidence through actively cultivating one's own perspective on the world and fitting it into a larger, collective understanding through active participation in its direction and evolution. The following definitions and discussions should inspire instructors to see this work in their existing practices as well as experiment with new ones that engage the metalanguage productively and critically.

Data

Data can, simply, be whatever precedes information; data is points of observation or measurement before they are connected to have meaning beyond those points. Kelleher and Tierney aggregate definitions of data across the information and scientific tradition into data as “abstractions of real-world entities (variable, features, attributes)—not the thing observed itself but a record of the thing” (2018, p. 39). Kitchin highlights purposeful abstraction as the key transformation that produces data (Figure 1): data spatiotemporally abstracts the world—selectively cutting something from its time and place—via a capture method (note-taking, photographing, digital duplication, etc.) to try to (re)construct information on the relationships between the observations. Salvo (2004) identifies data as the product of analysis, and Buckland (1991) describes data as collected records available for processing, in either a virtual or physical place. Therefore, a rhetorical definition of data should emphasize the purposeful transformation that occurs when data is collected, acknowledging the imperfection of abstracting and isolating something from the world/life when it is added to a dataset seeking to represent "lived" reality.

Data: purposefully collected measurements of the world (stored or recorded as measurements, either quantifiable or qualitative)

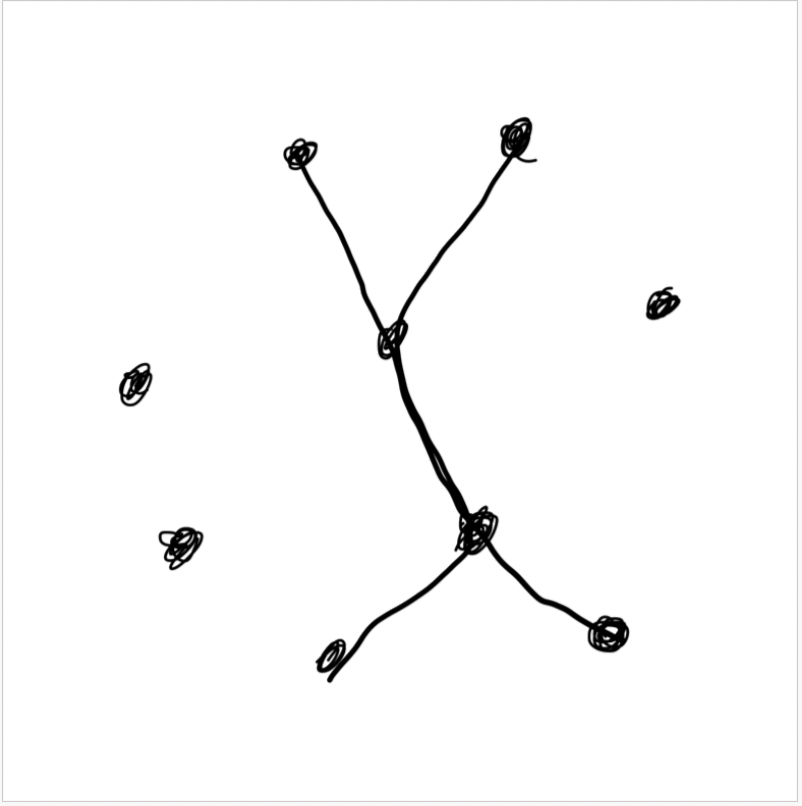

Data, as a practice of representing the world, may be thought of as using one’s experiences to locate and place dots on a map, as in figure 2.

Information

Rhetorically describing information must account for how a document (article, essay, post, video, media of any kind) is information when one reads it to entertain a new idea and how the same document becomes rhetorical data when combined with other sources to make a new piece of information (a narrative proposing a new idea/pattern). The Latin and Greek origins of information (informatio, morphe, or plērophoria) connote giving form to ideas to convey them to someone (i.e. design) (Buckland, 1991), and information-as-quantified-intelligence refers to bits assembled into a digital document (files, posts, etc.) for circulation, so information distinguishes itself through genre and the way one encounters it: as a document or narrative to an audience (Buckland, 2017). Data may possess the possibility "to inform," but it requires processing first; “raw data” is a misnomer, but to say a dataset “informs” without processing labor is disingenuous. Rhetorically, information is data transformed into a meaningful string/pattern/narrative, and data is a prospective component one may combine with others to produce information.

Information: data organized to make meaning (i.e. "pattern-making" and narrative over "quantifying intelligence" or producing "usable units")

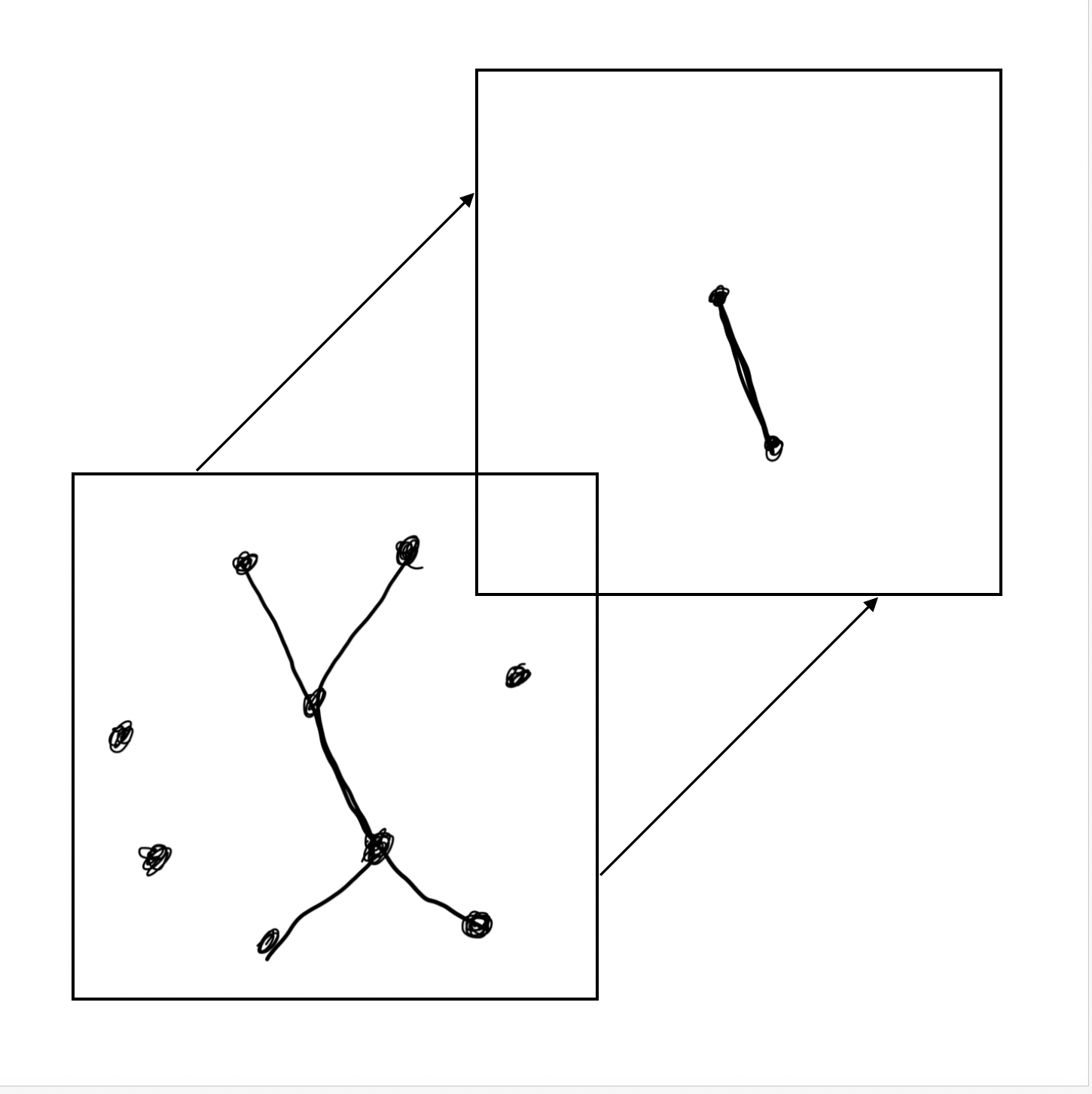

Information, as a practice of making meaning from specific points, may be thought of as connecting the located dots into a strand of meaning, as in Figure 3.

Knowledge

Knowledge is the point where information transforms from a legible pattern representing the world (something believable) into a way to understand the world (belief). Existence in the world is social, so knowledge implies a social, shared belief in some information, imparting a capacity to affect how one views existence (as part of the world). Information known by one person is a belief; knowledge is belief shared with others—something beyond information duplicated in a network (Buckland, 1991; Gleick, 2011). Kelleher and Tierney aggregate knowledge definitions for industrial Data Science as "information structured to be understood or applied" (2018, p. 56). Knowledge, therefore, has to be information multiple people share an experience of, through belief or other social agreement (citation of secondary accounts, etc.), enabling them to view the world a certain way together.

Knowledge-making invokes concern for futurity and power whether or not we explicitly acknowledge it. Foucault argues that Enlightenment moving truth (via knowledge) from the domain of monarchs (primacy of one person's beliefs) to the domain of (more) people made it social (Foucault, 1984; Foucault, 1975; Foucault, 1978). Buckland (1991) differentiates information from knowledge as an idea that is solely the possession of one person's mind, like a belief or opinion (pp. 351–352). Therefore, information rhetorically transforms into knowledge when multiple people can rely on and defend it because they find it legible and in alignment with information or other knowledge they already possess (i.e., not the same as information replicated in a network) (Gleick, 2011). Citation and peer review, for example, signify that given information aligns with other experiences and is worth circulating for consideration as knowledge. Building communities around practices of citation and circulation to produce knowledge is part of institutionalization, but institutionalization is not a requirement of knowledge-making; all that is required is two or more people believing and validating the same piece of information. Composition and Professional and Technical Communication (PTC) are integral to circulating information as part of argument and decision-making, whether through researching and synthesizing arguments about life and the world, document and interface design, or through theories of audience and the systems that shape data collection, pattern-making, and experience-sharing. The labor of knowledge-making, therefore, makes for a reasonable organizing concept for composition classes because it 1) accounts for disciplinary concerns of Rhetoric and Composition and PTC while 2) invoking empirical and active learning principles and 3) teaching institutional and industrial skills one needs to know to make the best use of information technologies (like generative AI) in any discipline (i.e. what is knowledge and how do we make and preserve it).

Knowledge: shared worldview based on a common experience of some information, through communication or application, by multiple people

Knowledge, as a shared experience of information forming joint belief, may be thought of as information strands overlapping and binding together into social bonds, as in Figure 4.

Wisdom

Wisdom is the completed feedback loop of knowledge-making wherein people apply, practice, or embody knowledge by reflecting the worldview they share with others through actions, exercising the social validation they feel from a community (institution, local, distributed, etc.). Wisdom invokes futurity in DIKW and implies ethics, making it an ideological minefield. Kelleher and Tierney aggregate wisdom definitions into, succinctly, "knowledge applied appropriately" (2018, p. 56). Wisdom is where data-driven fields like Data Science acknowledge their role in shaping the future beyond wrangling data into usable, informative units. The appeal of fields like Generative AI and Data Science that rely on large datasets, high-performance computing, and novel applications, is that they present wisdom (the future-tense) as a data-driven product more efficiently produced with machines (Kelleher & Tierney, 2018; Zuboff, 2019). Bluntly, industrialized data industries use empiricism to argue the future can be planned, so the next questions are "by and for whom?"

Wisdom, in other words, has to do with the why of knowledge-production: what ends and material, ecological, and social effects knowledge-work should pursue. This open-endedness confirms the rhetoricity of previous levels: the nature of the data and the form and meaning of the information experienced effect the knowledge underpinning wisdom. Traditional DIKW apolitically side-steps this question because it is borne out of an engineering and scientific tradition of figuring out how to efficiently transfer information and enable vast and various forms of information to exist simultaneously (Gleick, 2011). One might think of traditional DIKW solving a logistical problem of how to create and move knowledge with machines so the content of that information/knowledge can be interpreted by specialists. Rhetorical DIKW, therefore, takes up a humanist perspective by consciously considering and analyzing the process of thought becoming action/wisdom. Because rhetoric deals with decisions, mobility, and ecological consequences, this chapter proposes future-oriented democracy, justice, and survival as the rhetorical-ethical metrics on which to evaluate wisdom transformed from knowledge.

Survival means having a tangible future, as in the ability to both imagine a future and live into it (Kohn, 2013). Inability to imagine a future can empirically indicate insecurity and unsafety, something debilitating or traumatic depending on how long it lasts. Technocratic DIKW, for example, produces a privately-owned certainty of the future that is anti-rhetorical because it is not public/democratic (Zuboff, 2019; Johnson, Salvo, & Zoetewey, 2007). Democracy and justice refer to tireless and rigorous actualization of symmetry in people's relationships and participation and governance by identifying the greatest power asymmetries and applying appropriate asymmetrical responses to remedy them (Crenshaw, 1989). Survival, justice, and democracy ultimately deal with human-made institutions, power, and the nature of humans-in-the-world (Kohn, 2013) coming about through planning and cooperation. Rhetorically presenting DIKW can illustrate for students that cooperation with machines always has human results that we have to consciously craft, with or without machines.

Wisdom: future-oriented application of knowledge promoting democracy, justice, and survival

Wisdom, as action based on a shared worldview, may be thought of as people's knowledge strands set on a three-dimensional plane spatiotemporally persisting to form a feature of the world, or at least a new map of it, as in figure 5.

Rhetorical DIKW Pyramid

Recontextualizing the DIKW pyramid around rhetoric prioritizes concern for change, mobility, and justice that reflects present and future justice and sustainability (Aristotle, 2007; Edbauer, 2005; Hinks, 1940; Gries, 2015). It also builds metalanguage for students entering DIKW driven fields, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) wherein these concepts are gateways to dealing with human (and humanities) issues. The DIKW pyramid exists, in part, to rationalize how machines can process human experiences of the world, so metalingual ways to interact with these terms benefits humanists while maintaining their disciplinary concerns (Kelleher & Tierney, 2018). Furthermore, engaging with DIKW helps rhetoricians and compositionists re-engage with what "knowledge" means to people with other concerns, whose knowledge-making experiences are shaped by the ecology of circulation platforms and technology (Gunkel, 2009). Therefore, a rhetorical rendering of the DIKW pyramid would transform it from figure 1 to reflect the recursivity and futurity (connecting past, present and future) that rhetorical inquiry encourages, like in figure 6.

Figure 6's Rhetorical DIKW pyramid treats the rhetorical relationships between each level ecologically (that is, affecting each other across time and location) rather than as a linear process foregrounding necessary reduction for one to become the level above it. There is no hard rule about how “long” one level needs to last, like how sometimes we follow predetermined plans and take reflexive, situated action as our lives demand or allow. This pyramid aims to reflect daily life's messy interactions rather than assume all knowledge-production is a clean, laboratory-driven process, similar to the shift from rhetorical situations to rhetorical ecologies Edbauer (2005) argues for and the productive "trouble" that comes from recognizing recursivity is part of human experience (Law, 2004). This pyramid employs more verbs to emphasize the plastic and movement-oriented nature of rhetorical inquiry (i.e. navigating imperfect information) while resisting docility as a requirement. Circulation theory deals practically with the way 21st century communication revolutionized experience-sharing, but it also provides precedence for understanding that recursivity is inseparable from knowledge labor (going back to check premises or update assumptions, for example).

Information Theory avoids assuming that humans set out to make purposeful wisdom, implying it is always emergent and distributed, meaning a machine can accomplish the same labor apolitically. The logic at work implies humanity has innocently (maybe luckily) produced the world's current state because it is the best possible, or that our traditions and laws result from a higher wisdom we are pragmatically actualizing. Both visions imply conservative bias by holding the past as a standard. In one sense the "status quo" we feel is a reflection of the most prevalent knowledge. Socially and ecologically, a great deal of suffering is also perceptible in everyday life. Rhetorical DIKW emphasizes the choices and labor necessary to originate knowledge and emphasizes the skills students need to develop while machines automate portions of the labor. Thinking about wisdom as a purposeful and lasting product also highlights that we can choose to repair asymmetry and ecological damage (or not). Technology is arguably inalienable from rhetoric and writing, so Rhetorical DIKW emphasizes the skills that combine human and machine labor without investing in a particular technology's vision of writing or rhetoric, maintaining these acts as negotiation between human and machine for specific purposes. What's left to explore is how generative AI and Rhetorical DIKW interface with each other and fit into this rhetorical pedagogy.

Rhetorical DIKW Pedagogy with Generative AI (GenAI)

The language of (Rhetorical) DIKW translates the core value proposition of genAI/ChatGPT (used interchangeably hereafter) writing: ChatGPT remixes data (stored writing) to produce information (new/different writing) on demand. Lacking lived experience of the world, ChatGPT needs a user/human to "make" knowledge with—someone who provides prompts and socially audits the output, meaning ChatGPT cannot autonomously stray upward past information or downward past data. From the viewpoint of the user, ChatGPT may regularly produce novel information, but since ChatGPT only deals with data and information as an entity simulating conversation for the user, that information is more likely (like a used car) new-to-you. Overlayed on the DIKW pyramid, the user decides if what ChatGPT produces is knowledge, a pattern aligned with their own experience that could facilitate action/wisdom, before it can "be" knowledge. The fluidity with which humans move through DIKW levels is a testament to how ingrained they are in our nature, making it tempting to ascribe them to non-human entities, to anthropomorphize (Leaver & Srdarov, 2023). The (sometimes fleeting) moment where a user has the opportunity to agree with ChatGPT or not and why, is the pedagogical moment the remainder of this chapter focuses on. The tradition of institutional knowledge-making that DIKW translates for machines models this decision-to-agree interaction (i.e. information-to-knowledge) as happening between people: the Enlightenment found use for rhetoric in communication conveying arguments about the world to convince people to adopt them, for example (Bacon, 1605). With ChatGPT implicitly positioned as the user's multifaceted partner (librarian, tutor, secretary, copyeditor), ChatGPT prospectively offers the possibility to agree with someone on-demand and at-scale, particularly when human labor in these areas is underfunded or eliminated.

An overarching way to view ChatGPT’s impact, informed by Rhetorical DIKW, is how it manipulates time for the user. Marche (2022) implies that ChatGPT solves the problem of “write a paper” for students by having incomprehensible amounts of data at its disposal to remix, hence this chapter argues that Marche positions writing as a past- and present-oriented affair, converting data into information; data abstracts the world to preserve things outside the moment of collection, meaning data represents its spatiotemporal moment. It may seem pedantic to claim all data is of the past, but there's a practicality to it that cannot be ignored, particularly when collected data is modeled to predict the future based on past performance.2 Therefore, when ChatGPT takes a user prompt, picks data, and remixes it into an informative response, ChatGPT fundamentally applies abstractions of the past to the present concern to help someone with their future. Granted, ChatGPT will comply with requests to predict the future, but it, too, uses past data (training data presumed relevant to the question) to predict future performance. No matter what kind of information ChatGPT makes for the user, both ChatGPT and the user will be accepting that the past contains an answer, as the myth of transience dictates. ChatGPT, as an information technology, signals a truth about knowledge: all new knowledge is personal until it's not, which is to say that knowledge-making is a process of social acceptance. This makes ChatGPT an interesting and potentially highly-valuable tool to accelerate social acceptance of information as knowledge because it produces information (again) on-demand and at-scale as an uncanny conversation partner with a technocratic, expedient ethos (Katz, 1992).

The ultimate issue with this view of time, the world, and knowledge is that it tends to presume 1) that history is (or can be) complete and commonly understood and 2) the past is "right," and along with it the history of Eurocentric imperialism and colonialism, inequality, exploitation, and ecological destruction that produced it. There is no running from the past, but we must consider how remixing it as a de facto starting point will help us break from those traditions and, in fact, overcome them, with or without genAI. As argued above, attention to the future we wish to inhabit better promotes our role in producing it, contra the myth of transience. ChatGPT's meditation on past and present cannot promote our role alone; we must assert our role in the future. Hence, "skilled" use of genAI (whether in school, work, or other pursuits) will likely be influenced by command of one's own lived experience, along with data, information, and knowledge that informs one's understanding of ecological conditions to adequately interrogate and mold what ChatGPT produces. As Star and Strauss note, new technology displaces work rather than reducing it, and the user takes on new tasks (1999, p. 20).

In that spirit, this chapter ends with analysis of using ChatGPT in drafting and research as these (along with revision) are use cases students will likely try and workplaces will likely expect: drafting shorter work or parts of larger work, assembling information for easier consumption, and revising existing writing for readability or adjusting to different audiences. The chapter will continue using (Rhetorical) DIKW language to further illustrate the metalanguage in action. These use-cases likely are, barring regulation or labor agreements like the Writers' Guild of America's with movie producers, some of the likely new work we will do (Star & Strauss, 1999). Ultimately, because ChatGPT displaces liability for itself onto users, users at all levels have more responsibility for the writing they produce with ChatGPT because they are ChatGPT's managers, not its students, regardless of the feeling of wonder and discovery the product (and its media advocates) hopes to engender.

What's in a Prompt? Narrowing Ecologies to Situations for ChatGPT

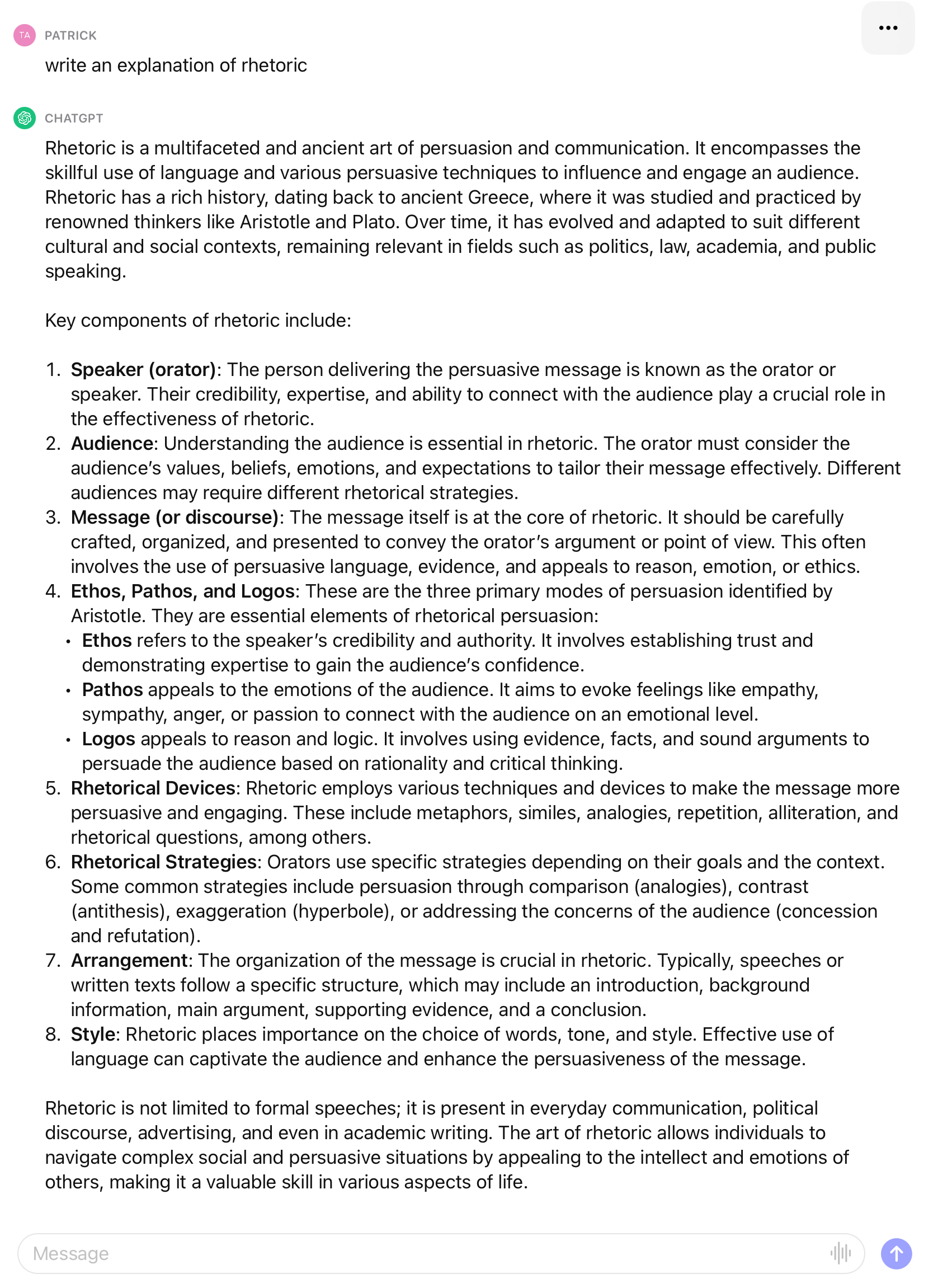

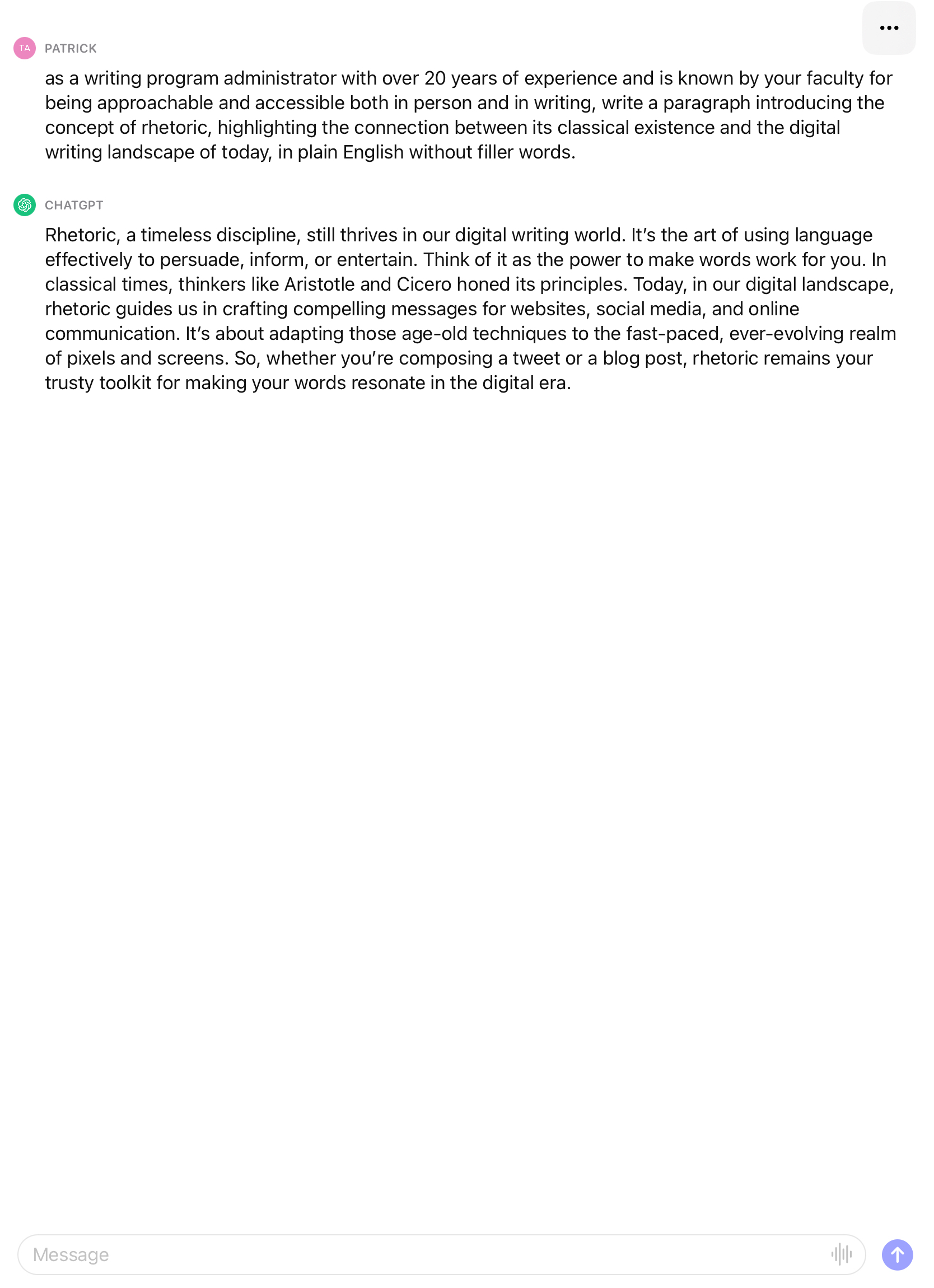

In interacting with ChatGPT, the user’s prompts form the rhetorical situation that informs ChatGPT’s responses. As such, one can impact ChatGPT’s output by being more direct about the rhetorical situation you want it to write in by: 1) giving ChatGPT an identity, 2) making a request, and 3) specifying the output (“As a freshman college student” + “write a discussion post on rhetoric” + “in a paragraph of at least 200 words”). This is a rough way to give ChatGPT its role as rhetor, a purpose, and specify context and/or audience. After seeing results, one can further adjust, provide examples to emulate, or add other miscellany by conversing with ChatGPT about the identity, task, or output. Detail and specificity in prompts tune the responses ChatGPT provides; prompts narrow the data ChatGPT will include in its response and specify the information the writer wants. Prompts, in other words, narrow the ecology expressed through data down to a rhetorical situation for ChatGPT's work, meaning the writer needs a sophisticated command of that situation to get the "best" results. The writer, therefore, will need to know about the ecology and situation to know if ChatGPT has produced something useful or valid; the writer already needs an idea of the data necessary to produce the information wanted, and lived experience to effectively agree or disagree with the information ChatGPT assembles. For instance, consider the differences between starting a draft with “write an explanation of rhetoric” (figure 7) and “as a writing program administrator with over 20 years of experience who is known by your faculty for being approachable and accessible both in person and in writing, write a paragraph introducing the concept of rhetoric, highlighting the connection between its classical existence and the digital writing landscape of today in plain English without filler words” (figure 8).

ChatGPT will respond to both affably because it is programmed to comply with most requests, but the user always supplies their own assurance that the difference or nuance between the two responses is significant. The lived experience of the user determines how they will perceive differences in the responses and decide to trust one over the other based on their needs. If the user has no more insight into the rhetorical situation of the second prompt than the first, they may treat it as a coin flip or choose the response of the second prompt because it appears more precisely formed—but then we must ask: how would one form the second prompt without rhetorical insight to construct that situation? If one has more insight/knowledgeable lived experience on which to draw concerning the second prompt, that user will bring a more critical eye based on the data and information they have incorporated for their lived experience as part of their professional knowledge: what characteristics is “over 20 years of experience” imbuing? “Approachable” to what faculty and under what assurance? What subject position does the Writing Program Administrator (WPA) occupy, either to themself or to other faculty? Why not “approachable” by students? What authority does ChatGPT derive from “20 years of experience,” “approachability,” and social “accessibility?” Are these the best traits for a WPA? Is there an assumed whiteness or masculinity in the image of WPA that ChatGPT is conjuring? Would we be more or less pleased with the result if we asked ChatGPT to write as a person of color or a woman specifically? Would ChatGPT insist people of color or women have no distinguishable language uses? What does “plain English” mean? Someone without the lived experiences (and data and information informing them) necessary to know these questions are important would be equally ill-equipped to judge the reliability of ChatGPT's response.

Using ChatGPT for research presents a different set of issues. Users asking ChatGPT to explain something or answer a question may expect an interpretation of the world rather than a synthesis of spatiotemporally contingent data without concern for the difference. In the expanded DIKW pyramid from Kitchin (2014) (figure 1), the world is the base of the pyramid as a reminder that we are always studying and trying to understand the world as an unending process that includes us. The Rhetorical DIKW pyramid (figure 6) carries on this notion of unending spatiotemporal unfolding forward (Gries, 2013), agreeing there is no end to what we can "know" about the world (social, biologically, ecologically, etc). DIKW rests on the world because it assumes knowledge-production reconciles people's lived experiences through gathering data and making informative arguments, creating a check on mis- or disinformation. With ChatGPT we have, in essence, a (generative artificial) intelligence whose conception of the world is entirely from collected data; genAI does not have a lived experience of its own. All of ChatGPT's "intelligence" comes, it seems, from writing scraped from the internet and other digital sources (then coached by untold OpenAI workers and wrapped in a black box). ChatGPT is, in this sense, a being of pure circulation. The implications of this are manifold, particularly when considering the examinations of mis- and disinformation on the internet and calls for renewed information literacy pedagogy in the last ten years.

In the context of this chapter, Rhetorical DIKW metalanguage helps introduce ChatGPT's capabilities and limitations in assisting with research, since its ability to summarize data (a way to convert data to information in DIKW parlance) is one of its immediately attractive use-cases. ChatGPT's connection to the world is only through data, whereas humans live in the world and draw inspiration from it (Suchman, 2007), so users must be prepared to compare ChatGPT's results to their lived experience and be ready to check ChatGPT's work (find data and information and learn the lived experiences of others to confirm or correct ChatGPT output).

ChatGPT likely fits exploratory research best, similar to how one would use Wikipedia or search engines to explore a new topic, learn discourse trends and markers, and develop research questions. Most likely, ChatGPT will draw from pages Wikipedia editors and Google can access, anyway. In research, genAI offers more expedient usability (than Wikis or search engines) but their lack of knowledge famously produces "hallucinations" from their programmed desire to return answers and maintain the dialogue (Hicks, Humphries, & Slater, 2024): such earnest commitment to fulfilling user requests makes the user, again, responsible for believing ChatGPT. Hence, ChatGPT can assist exploration, but still requires precise prompts and user verification as part of the writing/research process.

While it is most expedient to say to ChatGPT “tell me about X,” one can also direct ChatGPT to filter data and information through an identity, task/purpose, and output/genre. Identities may include: “You are a (SUBJECT) expert with 30 years of experience and lots of awards for excellence,” or “You are an expert (PROFESSION). You are highly experienced at (SUBJECT) research and finding valuable insights.” Again, how ChatGPT constructs the identity is rhetorical. How does one approximate this through data? Does ChatGPT have access to the writing of these people? Is that where the totality of their techne is captured (Van Ittersum, 2014)? Who are we picturing in these identities? As before, to know if ChatGPT has captured the identity, one needs to know about that identity, too. ChatGPT may end up the basis for one's own exploratory research as a point of comparison. Adding “with citations of real sources in APA/MLA/etc.” can approximate using ChatGPT similar to using Wikipedia for farming scholarly sources.

What Rhetorical DIKW adds here is language to describe the tasks and labor necessary to use ChatGPT effectively this way. Command of the rhetorical situation is the difference-making factor between users when it comes to how well they can use the output of a prompt in/as a draft or if they can form an effective prompt in the first place. Therefore, invention with ChatGPT involves gathering together data and information (observations, experiences, and patterns) to judge if ChatGPT's products pass the sociability test—if they are worth agreeing with or, more productively, what tweaking and modification is required to fit the situation more effectively. If ChatGPT is a viable way to generate rough drafts, in either school or the workforce, the difference-making labor a user will do with it is build and maintain ongoing understanding of the rhetorical ecology and specific situations in which they will consult ChatGPT through having their own data and information at-hand to provide social approval or critique of the AI's proposals. Therefore DIKW-informed composition and communication classes can teach students the role rhetorical data and information play in constructing rhetorical situations from ecologies before presenting them to ChatGPT. In doing so, composition classes have an opportunity to stress the relationship between the individual and society, and introduce the importance of wisdom: the consequences of worldviews on the ecology. Therefore, writing classes need to emphasize rhetorical situation and ecology more as ways to produce discourse and engage students in invention activities that build their understanding of writing projects as always the product of spatiotemporal situations in larger ecologies.

Conclusion

GenAI appears in some ways as another attempt to create "perfect information" through technology that libertarian, neoliberal capitalism craves, releasing humanity from the need to reconcile its vast and disparate lived experiences through anything other than markets. The impulse to have perfect information at instant command is an impulse similar to the myth of transience: to find the solutions to our problems in what has come before and treat data modeling as a benevolent dictator with a face that diligently uncovers the way forward that past performance lays out for us. Rhetorical examination of DIKW explains how public concepts of material knowledge—so-called immutable constants, "facts," or "truth"—are so contentious today: DIKW presupposes that human critical attention (i.e. lived experience) organically intervenes in observations becoming action, and that machines can learn to replicate that critical attention. Criticisms of "fake news" and calls for better information literacy over the past ten years imply this matter is ongoing. If we accept that "good" information derived from data leads to positive impact on the future, it is tenable to argue that "bad" information is an impediment, but DIKW logic does not engage in defining "good" or "bad" information as a rule. Furthermore, when knowledge is formed from observations, and information technology accelerates communication, it is logical to assume that the observations and patterns people use to form their worldview originate increasingly in digital sources, particularly when their design facilitates more circulation (Ridolfo & Devoss, 2007). This question is particularly relevant to genAI, whose entire received data about the world is the product of digital circulation. Hence, Rhetorical DIKW as part of the writing process can not only help students reexamine their writing processes in the context of heightened digital circulation and AI writing, but also open avenues to connect it to active learning and reposition problem-posing pedagogy by using DIKW to connect writing to action and decisions beyond documenting the world. Writers, artists, and other workers must have a say in the role genAI will play in their fields. In the meantime, students should understand that they have more responsibility for work they do using AI since they supply the critical and material elements of the knowledge-process when they use it, and they are not absolved from collecting observations and organizing them in the process.

For now, two provisional conclusions emerge. First, rhetorical situation and rhetorical ecology remain fruitful to composition pedagogy with or without ChatGPT, and prompts-as-interaction with ChatGPT arguably make ecological and situational concern more important. Forming a prompt is a kind of rhetorical invention (and a writing challenge in itself), and knowing the situation informs students' ability to judge ChatGPT's writing. Pedagogical emphasis on the rhetorical situation also frames the labor proposition ChatGPT presents: to get better results, one needs to precisely form prompts, requiring an invention and writing process of its own. Those that do that rhetorical work will get better returns, but it is unclear if that "saves" time for the writer or merely increases the expectations of their capability. Second, assignments that primarily ask for summary, comparison, or analysis are, in the abstract, scooped by ChatGPT, since they engage in the kind of past- and present-oriented writing (internalization of complex topic or subjects) aimed at assembling data into information that ChatGPT is built to excel at. To challenge ChatGPT (or writers expediently relying on it), assignments need to actively combine past experience (data that originates both within and outside the writer) with a problem and require future-oriented action to be more pedagogically productive.

Either way, Rhetorically-informed DIKW metalanguage helps teachers and students talk about rhetorical situation and ecology in ways that invite comparison between the writing process of students as individuals (with their own observational, pattern-making skills, and lived experience to draw on) with ChatGPT as a (black-boxed) amalgam of collected texts: both choose data to form the pattern they will present to someone, but that does not make them identical processes, and it reaffirms the importance of individual perspective and social participation. Ability to critique information based on the wisdom it may generate is a difference-making labor a human will provide if genAI remains a commercial success. Regardless, a concern for futurity is an evergreen “skill” for all humans.

References

Aristotle. (2007). On rhetoric: A theory of civic discourse. Kennedy, George A. (Trans.). Oxford University Press.

Bacon, Francis. (1605). Advancement of learning. Devey, Joseph (Ed). P.F. Collier and Son.

Bender, Emily M., Gebru, Timnit, McMillan-Major, Angelina, & Shmitchell, Shmargaret. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? 🦜. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT '21). Association for Computing Machinery. 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922

Buckland, Michael K. (1991). Information as thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 42(5), 351–360.

Buckland, Michael K. (2017). Information and society. MIT Press.

Cooper, John M. (Ed.). (1997). Plato: Complete works. Hackett.

Crenshaw, Kimberle. (1989). demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1, 139–167.

Edbauer, Jenny. (2005). Unframing models of public distribution: From rhetorical situation to rhetorical ecologies. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, 35(4), 5–24.

Foucault, Michel. (1975). The means of correct training. In Paul Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader. Vintage Books.

Foucault, Michel. (1978). Right of death and power over life. In Paul Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader. Vintage Books.

Foucault, Michel. (1984). What is enlightenment? In Paul Rabinow (Ed.), The Foucault reader. Vintage Books.

Freire, Paulo. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. 30th Anniversary Edition. Continuum International Publishing Group. Ramos, M. B. (Trans).

Gleick, James. (2011). The information: a history, a theory, a flood. Pantheon Books.

Gries, Laurie. (2013). Iconographic tracking: A digital research method for visual rhetoric and circulation studies. Computers and Composition 30, 332–348

Gries, Laurie. (2015). Still life with rhetoric: A new materialist approach for visual rhetorics. Utah State University Press.

Gunkel, David J. (2009). Beyond mediation: thinking the computer otherwise. Interactions: Studies in Communication and Culture 1 (1), 53–70.

Hicks, Michael T., Humphries, James, & Slater, Joe. (2024). ChatGPT is bullshit. Ethics and Information Technology, 26(2), https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-024-09775-5

Hinks, D. A. G. (1940). Tisias and Corax and the invention of rhetoric. The Classical Quarterly 34(1/2), 61–69.

Johnson, Robert R., Salvo, Michael J., & Zoetewey, Meredith W. (2007). User-centered technology in participatory culture: Two decades “Beyond a Narrow Conception of Usability Testing.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 50(4), 320–332.

Katz, Steven B. (1992). The ethic of expediency: Classical rhetoric, technology, and the Holocaust. College English 54(3), 255–275.

Kelleher, John D., & Tierney, Brendan. (2018). Data science. MIT Press.

Kitchin, Rob. (2014). The data revolution: Big data, open data, data infrastructures and their consequences. Sage.

Kohn, Eduardo. (2013). How forests think: Toward an anthropology beyond the human. University of California Press.

Law, John. (2004). After method: Mess in social science research. Routledge.

Leaver, Tama, & Srdarov, Suzanne. (2023). ChatGPT isn't magic: The hype and hypocrisy of generative artificial intelligence (AI) rhetoric. M/C Journal, 26(5), https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.3004

Locke, John. (1689). An essay concerning human understanding. The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes. London, 1824 edition.

Marche, Stephen. (2022, December 6). The college essay is dead: Nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-ai-writing-college-student-essays/672371/

Noble, Safiya U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press.

O'Neil, Cathy. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Crown Publishers.

Ridolfo, Jim, & DeVoss, Dànielle N. (2009). Composing for recomposition: Rhetorical velocity and delivery. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, 13(2), http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfodevoss/remix.html

Rose, Mike. (1985). The language of exclusion: Writing instruction at the university. In The Norton Book of Composition. Ed. Susan Miller. W.W. Norton, 2009. 586–604

Salvo, Michael. (2004). rhetorical action in professional space: Information architecture as critical practice. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 18(1), 39–66. DOI: 10.1177/1050651903258129

Star, Susan L., & Strauss, Anselm. (1999). Layers of silence, arenas of voice: The ecology of visible and invisible work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 8, 9–30.

Suchman, Lucy. (2007). Human–machine reconfigurations: Plans and situated actions, 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press.

Van Ittersum, Derek. (2014). Craft and narrative in DIY instruction. Technical Communication Quarterly 23(3), 227–246. DOI: 10.1080/10572252.2013.798466

Zuboff, Shoshana. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. PublicAffairs.

1Emphasis added on data, information, knowledge, wisdom, and world to call attention to the metalanguage used in practice.

2O'Neil's work on data-driven policing perpetuating asymmetrical policing of non-white and low-socioeconomic neighborhoods, and Noble's work on search engines perpetuating discrimination by shaping available information demonstrate this (O'Neil, 2016; Noble, 2018).