Interfacing Chat GPT: A Heuristic Approach for Improving Generative AI Literacies

Desiree Dighton East Carolina University

Introduction

In “Politics of the Interface” (1994), Selfe and Selfe imagined a future in which writing technologies would be shaped by computers and writing research. As the field of writing studies has developed alongside the evolution of personal computing, we've adapted our writing theory, practice, pedagogy, and research to social and technological transitions, maintaining a commitment to student agency. To support students in becoming effective writers in academic, professional, and social contexts, we emphasize flexible, individualized processes like brainstorming, researching, drafting, integrating feedback, revising, citing source material, and more. We've spent decades convincing our students that the process of generating a text is as valuable as and inseparable from final written products. Over the years, we've advocated for more inclusive writing pedagogies and assessment standards that value student writing processes and their written products. We've moved rubrics away from a "Standard" Written English and toward honoring students' home languages and linguistic diversity. As a field, we've largely embraced technologies as beneficial for helping students learn, assert agency, and write more effectively in our classrooms and beyond. Many of us eagerly adapt our writing pedagogies to technologies as they emerge, wanting our students to gain practice with innovations that may become important to their futures. In the age of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GAI) like ChatGPT, Selfe and Selfe’s call for writing studies to engage both “students and computer specialists to re-design/re-imagine/re-create interfaces” becomes a call for critical literacy development that takes on renewed urgency within our classrooms and beyond (p. 495).

Video Transcript

This video has no audio. A split screen shows a plain white background on the right with the words "Get Started" in bold above two blue buttons in the center: Log in and Sign up. The left side features a pale golden background and an animation of text instructions that ChatGPT can presumably assist with:

|

The Interface as a Site of Critical AI Literacies

Selfe and Selfe (1994) urged us to see interfaces as “an interested and partial map of our culture and as a linguistic and cultural contact zone that reveals power differentials” (p. 485). While Grabill (2003) acknowledged that interfaces may grant users access to technology that helps them solve problems, that access also shapes user behavior and attitudes toward dominant norms. Stanfill (2015) observed how interfaces act upon their users through their circulation and designs that lose their visibility and legibility as users gain greater access to underlying systems, causing interfaces to become frames we look through (Jones, 2021; Selfe & Selfe, 1994; Stanfill, 2015). Interfaces, like all designs, are never actually transparent or neutral, but instead carry dominant “values of our culture—ideological, political, economic, educational” (Selfe and Selfe, p. 485). Interface analysis opens opportunities for building critical literacies as analyzing the interface has potential to “unconceal” dominant values and illuminate ‘contact zones’ that limit and enable users unevenly through power differentials. In our classrooms and other communities, we can build critical literacies heuristically through interface analysis of generative AI (GAI) applications like ChatGPT. Such interface analysis should focus both on the materiality of interface design and its circulation. Doing so may advance awareness of what Selfe and Selfe identified as the interface’s ability to norm users to the dominant values and behaviors. These norms show up in interface features and “grand narratives which foreground a value on middle-class, corporate culture; capitalism and the commodification of information; Standard English; and rationalistic ways of representing knowledge” (p. 494).

As we rush to prepare students with GAI knowledge and skills, we should attend to building critical literacies that explore the power dynamics of GAI interface designs. It is through reimagining and redesigning technical aspects like interfaces that we can work against their dominant norming power and “avoid disabling and devaluing non-white, non-English language background students, and women” among other harms (p. 495). With this paper, I offer tactics for classrooms and other communities to develop interface heuristics as critical AI literacies. Pedagogically, taking a heuristic interface approach provides an adaptable framework for scaffolding critical student AI literacies, even as GAI and its interfaces change and writing instruction strives to adapt in precarious times.

Developing critical GAI literacies builds upon our field's established understanding of the integral relationship between technology, writing, literacy, and power (Gee, 2004; Hawisher & Selfe, 2000; Selber, 2004; Selfe, 1999; Yancy, 2003). With the recent public release of GAI applications like ChatGPT, groups like the MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI urge us to use our expertise to develop literacies around “the nature, capacities, and risks of AI tools” (p. 7). To cultivate critical literacies, we can "unconceal" GAI's values and risks, in part, by analyzing the point of contact between these technologies and humans: interfaces. To begin, we can ask how a particular interface design guides our use and provides transparency about its processes, systems, and data. We can invite community discussions about how GAI circulates through public conversations like promotional materials, popular media, and everyday conversations. Getting at these dimensions—the technical and the cultural—are crucial to building critical AI literacies in our classrooms and other communities. The next section briefly describes my rationale for choosing ChatGPT as the GAI application under discussion and for dynamically adapting classroom interface heuristics to other GAI interfaces and community experiences.

The interface descriptions provided throughout this paper often reflect specific versions and times in ChatGPT's quickly changing design and functional history. To the degree possible, I’ve indicated specific versions and dates, but elements of ChatGPT’s interface and processes may have changed beyond or escaped the timing of this writing and the classroom activities described. Even though ChatGPT and other GAI designs will continue to change, historic descriptions and lived experiences of the interface help us track these changes and their embedded cultural values over time. Heuristic analysis should be adaptable to future iterations, other tools, and new communities. As a brief case study, I’ll share my experience developing interface heuristic analysis to build critical GAI literacies with undergraduate writing students during ChatGPT’s initial public release.

ChatGPT: A Conversational Interface

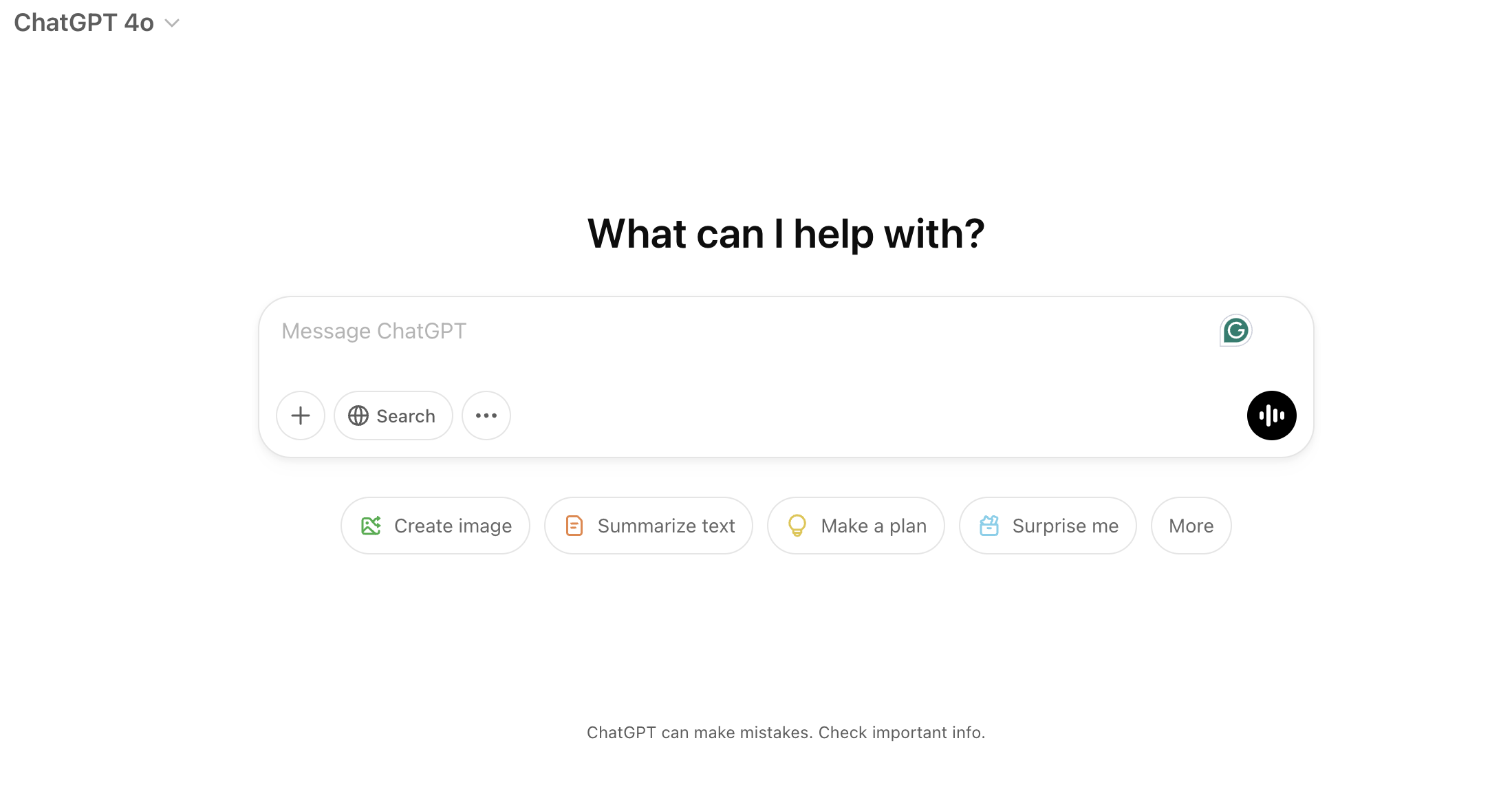

ChatGPT's widespread and rapid public proliferation hinged, at least in part, on its interface design. With ChatGPT, GAI could be accessed by any user who could type or otherwise enter human language conversationally into a text field. With its chatbot interface, typical features like tool bars, drop down menus, and action buttons like “submit” have been omitted to prioritize the chat window (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). While chatbots regularly appear on website interfaces to assist users in navigating sites, services, and information, GAI web-based applications like ChatGPT are chat-based interfaces. In other words, the human-like conversations that make public access to GAI web-based applications like ChatGPT possible are the conversational interfaces, allowing us to use our natural human language rather than typical interface features to access technological processes and data.

Embedded Values and Rhetorical Frames in AI Interfaces

Since its release in November 2022, ChatGPT's interface has included a variety of disclaimers and hedges about the accuracy and safety of its responses. For example, in 2024, a faint message under the chat window stated, “ChatGPT can make mistakes. Check important info” (Figure 3). Such disclaimers detach accuracy and safety from its generated content while continuing to provide that content to users.

These “mistakes” are part of what drives GAI controversies, aversions, and lawsuits. Prior to its initial public release, OpenAI tested and reported that improvements made to GPT-4 to mitigate error and harm are “limited and brittle in some cases” (Abstract, GPT-4 System Card, March 23, 2023). The report acknowledged the need for more safety research in the “absence of anticipatory work to address how best to govern these systems, how to fairly distribute the benefits they generate, and how to fairly share access” (p. 49). The report is especially concerned about GPT’s “latent” capabilities and its knack for “generating discriminatory content favorable to autocratic governments across multiple languages” (p. 51). GAI’s likely impacts, the report stated, reach beyond its content generation to influence knowledge and culture, stating, “AI systems will have even greater potential to reinforce entire ideologies, worldviews, truths and untruths, and to cement them or lock them in, foreclosing future contestation, reflection, and improvement” (p. 49). However, as users interact with ChatGPT’s interface, none of those risks are apparent beyond the faint disclaimer about potential “mistakes” in content generation. ChatGPT’s interface, like other GAI web-based applications, lost many of its conventional Graphical User Interface (GUIs) elements and user options to become more like a conversation portal to powerful but concealed and mysterious processes. GAI chat-based interfaces open opportunities to critically examine the materiality of these designs and track their changes over time. Doing so will give us greater understanding—the critical GAI literacies—to see GPT’s embedded values and how they circulate through its interface versions, user experiences, and public conversations. ChatGPT’s interface enabled widespread use and rapid integration into our personal technologies and other applications, enabling much of GAI’s vast public power. This paper will briefly examine how heuristic interface analysis can unmask interface design as it attempts to hook users, transmit concealed values, and obscure processes. GPT’s affective flirtations, as I’ve termed them, make developing critical GAI literacies especially challenging and important for discerning GAI’s power and place in our classrooms and beyond. Writing classrooms are important sites to check GAI’s power through the interface analysis of its “small but continuous gestures of domination and colonialism” (Selfe & Selfe, p. 486). While many of us realize we may not be able to determine students’ GAI use, building critical literacies in community with them is one avenue we still have for limiting its power.

Analyzing ChatGPT's Interface: A Heuristic Approach

At the time of this writing, GPT’s abilities to generate a response primarily relied on two main design features of its interface: (1) a message box for user prompts and (2) the much larger window streaming GPT's responses. Secondary features included a chat history window, a “new chat” button, and user settings. An icon allowed for sharing chat transcripts, and a question mark icon provided “help” resources, “terms and policies,” and “keyboard shortcuts.” Users could delete chats but couldn’t alter or edit GPT’s responses within the interface window. These design choices and others shape our interactions with the interface and either empower or limit user ability to access a wider range of technical and data possibilities.

Usability Heuristics and the ChatGPT Interface

Jakob Nielsen (1992) first championed heuristic interface evaluation to identify “usability problems” (p. 373), defined as aspects that hinder understanding, use, or satisfaction. Nielsen advocated for evaluators to assess compliance “with recognized usability principles” (1992, p. 373). Today, these principles guide heuristic and ergonomic evaluation methods standard in contemporary interface design, development, and evaluation. Pribeanu (2017) noted that interface design includes user guidance, including prompting, feedback, information architecture, and grouping to enhance usability while also guiding users toward the intended uses imagined by companies, programmers, and designers. In chat-based GAI interfaces, typical dropdown and other options are mostly absent, constraining agency within the chat window and the users’ abilities to use conversation, or prompting, to achieve an output.

In a 2023 OpenBootcamp UX/UI Challenge using Nielsen-based heuristics, Athul Anil (2023) found GPT’s interface passed every design standard except for a “minor usability problem related to aesthetic and minimalistic design” (n.p.). In his redesign recommendations, Anil recommended more minimalism, eliminating interactive elements to reduce visual clutter. Anil's assessment of ChatGPT's interface indicates that at least in some UI/UX circle, ChatGPT’s interface is a nearly flawless design. But for what and whom is it designed?

Your Super-Smart Friend, ChatGPT

One of GPT’s most prized features is its ability to efficiently simplify complex information for non-expert users. Since most of us, including our students, have trouble grasping and explaining its processes, I asked GPT to explain how it works to someone with only basic computer knowledge. GPT-4 stated, “Suppose your friend spent years reading from millions of books, articles, and other texts. They didn't memorize everything, but they learned patterns, like how sentences are structured, what kind of answers people give to certain questions, and lots of information about the world” (ChatGPT, October 19, 2023). Now, it doesn’t have to find or locate the answer in any specific texts: “Instead, they think about all the patterns they've learned and try to generate a response that makes the most sense based on what they know. It's like they're completing a sentence, but the sentence is your answer” (ChatGPT, October 19, 2023).

It’s worth repeating: ChatGPT wants to complete your sentences for you. It values the ability to remake knowledge and “personalize” it behind user interface windows that keep its processes mostly invisible. The interface limits user input to what can be accomplished through human conversation—a design that guarantees ease of use without interface features or backend access points to control the processes and data involved in that use. Added to this unequal equation is that when we establish accounts and ask GAI applications like ChatGPT questions, often prompting with more specifics to get better responses, our interactions provide ChatGPT with broad access to us, access that becomes their data, the value of which, at scale, is more compelling to ponder than its personalized responses.

GAI web-based applications like ChatGPT often include data protection policies and ways for users to opt out of some levels of data collection and brokerage. Open AI’s privacy policy states that it collects a wide range of “Personal Data,” providing only a conditional option for users to protect the use, not the collection, of their “Content to train our models.” To do so, users must locate their settings, click data controls, and click off the default, labeled, “improve the model for everyone.” This option, according to its policies, protects user inputted content from being used to train its models, while not allowing users to opt out of further data collection or privacy, stating ChatGPT’s parent company may “share your personal information with affiliates, vendors, service providers, and law enforcement” (O'Flaherty, 2024). While we may have some federal and state data privacy protections, Satory et al. (2024) found “significant gaps in the effectiveness and enforcement of data privacy laws, cybersecurity regulations, and AI accountability” (p. 657). Furthermore, the research team noted that “the accountability of AI systems remains a critical concern, with current regulations falling short in addressing issues of transparency, bias, and ethical decision-making” (p. 666). Despite its potential dangers and harms, GAI interfaces position users to accept its terms and “mistakes” to gain access to the power of artificial intelligence.

ChatGPT’s interface tells users to accept its dangers as we would ordinary human mistakes while declaring it’s technical neutrality, effectively saying to the user, "I am a friend that doesn't have feelings, emotions, or consciousness. I'm just a tool, like a very advanced calculator for language." Appeals to human qualities and emotions like friendship and trust are some of ChatGPT's winningest affective flirtations. They nudge us where we are soft, using our human emotions and insecurities, to accept GPT as we would a human friend. These affective flirtations work against our resistance to the application, softening our defenses and norming us to GPT's method of collaboration.

We can accept UX/UI heuristic evaluations of GPT's interface, its flirtatious and humanizing appeals for our friendship, knowing that acceptance demands tolerance for potential serious errors and harms. Alternatively, we can develop interface heuristics that forge critical AI literacies—perhaps the few protections we have to design and implement, at least in our classrooms. As Agboka (2012) noted, however, heuristics too often reflect principles of “Big Culture” ideologies like those embedded in Nielson’s heuristic tools. Instead, writing studies should create dynamic, flexible heuristic frameworks that are adaptable to cultural differences and technical changes in our classrooms and other communities. Structured yet flexible GAI heuristic evaluation can help students discern ChatGPT’s benefits and limitations as “personalized” writing tools, opening more opportunities for them to claim agency in its use.

More broadly, heuristics based on writing studies theories and pedagogies promote more nuanced and culturally aware evaluation of interface design beyond our classrooms. As writing studies scholars have pointed out, the influence of technologies is not confined to particular interactions—an interface functions as a circulatory, "world-making process" (Jones, 2021). As Grabill (2003) pointed out, “to ignore infrastructure, then, is to miss key moments when its meaning and value become stabilized (if even for a moment), and therefore to miss moments when possibilities and identities are established” (p. 464).

Chat GPT is to Writing as a Parent is to a Child

If you asked most college students how ChatGPT works, I’d guess that most would answer like most mine did recently: Artificial Intelligence. Even when I asked students for more details and specifics, most students shrugged or repeated “AI” with air quotes and question marks in their voices. Gallagher (2023) found the language we use to talk about generative AI (GAI) “indicates alignments with certain ideologies” (p. 151). He said more technical terms like Machine Learning (ML) may help students have greater awareness of its data and processing aspects while Artificial intelligence (AI) may help them understand how public “hype” is created around these technologies and products.

Writing studies has a long history of expertise in the ideological function of language. We teach students to grapple with language’s nuance and power and to use language knowing it could alter real-world consequences (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Burke, 1969). We also teach them that, especially with our internet-enabled global world, our original messages could circulate to new audiences and have new benefits and harms we can’t always anticipate (Gries, 2018; Jones, 2021). What do our students imagine when they hear a phrase like “powered by AI”? We can work to illuminate how these phrases circulate Selfe’s dominant narratives and operate as Burkean frames of acceptance, but more basically, we can talk about how this language makes them feel, how it works to sell products and levers the public towards uncritical use and consumption. Antoine Francis Hardy (2020) stated, “public rhetors use frames as a means by which they adopt attitudes towards society and prescribed said frames for audiences” (p. 30). Frames, metaphors, and narratives are the cultural languages by which we communicate and understand the world. They are also the rhetorical mechanisms by which GPT circulates, gains widespread acceptance, and, increasingly, becomes the status quo.

In “AI as Agency without Intelligence,” Floridi (March 2023) explained that contrary to perceptions about the advanced intelligence and functionality of ChatGPT-4, it does not understand as humanly as it would like us to believe. Instead, it “operates statistically—that is, working on its formal structure, and not on the texts they process” (p. 14–15). ChatGPT doesn’t evaluate texts as humans might, analyzing the nuances of authorial credentials, publication characteristics, writing genre conventions, scholarly peer review, and other types of publishing processes and ethics. In GAI interfaces like ChatGPT’s, where is the human agency to “pay close attention to how it [a text] was produced, why and with what impact?” (Floridi, 2023, p. 15). Instead, GAI interfaces have been designed to obscure their process and prevent users from participating more fully in shaping their personalized outputs.

Like all interfaces, ChatGPT’s design can and does change through developer and company implemented adjustments. These redesigns could take many forms, including versions that would enable greater user agency and system transparency. For instance, when I prompted ChatGPT to provide a list of the most influential computers and writing scholars, I had to further prompt it to be more inclusive by asking for “marginalized or non-white scholars.” GPT was cheerful about regenerating its response, stating, our field “has been enriched by the contributions of marginalized and non-white scholars, who have brought unique perspectives and important critiques related to race, culture, identity, and digital spaces” (ChatGPT, October 20, 2023). If inclusion were given importance by its designers and programmers, perhaps ChatGPT could calculate and provide results to users within more inclusive calculation metrics or give users the interface controls to indicate they’d like more inclusive data metrics and results. Prompt engineering is presently the only way to try to generate more inclusive results, which puts the onus on the user, not the underlying system. With GPT's texts increasingly passing human expert judges and plagiarism detectors alike, our ability to discern between human and machine generated texts is closing, even as we remain uncertain and concerned about GAI’s impacts on equity and inclusion in how we make and circulate meaning through texts.

In the Proceedings of the Digital Humanities Congress (2018), Henrickson observed that more research is needed to better understand how ordinary people ascribe authorship to computer-generated texts. Focusing on 500 participant responses, she conducted a “systematic analysis of computer-generated text reception using 'Natural Language Generating' (NLG) technologies.” Henrickson found the concept of an “author” conformed with “conventional understanding of authorship wherein the author is regarded as an individual creative genius motivated by intention-driven agency” (Conclusion, para. 1). Henrickson further observed participants likening the writing process of NLGs to that of a parent (developer) passing along knowledge to a child (an AI NLG/LLM system like ChatGPT), noting that this parent-child narrative humanizes and thereby normalizes the technology as an authority. Henrickson found that users automatically responded to this technology as they would to other people, concluding that most “readers feel that the system is capable of creating sufficiently original textual content” and “the process of assembling words, regardless of developer influence, is in itself enough for the system to attribute authorship” (The NLG System as Author, para 3). If, like Henrickson observed, our students believe GAI can author texts, what entry points do they have for claiming agency over the texts it generates? Does its credibility and authority extend to every possible writing topic and task? With these questions and more, is it any wonder our students are confused about how to move forward, not to mention the weight and variety of institutional and instructor GAI policies and the threat of AI detection software. In this climate, the students “may experience an increased sense of alienation and mistrust” and “increased linguistic injustice because LLMs promote an uncritical normative reproduction of standardized English usage that aligns with dominant racial and economic power structures” (MLA-CCCC Task Force on Writing and AI, July 2023, p. 7). As these concerns point out, students will experience uneven dangers and benefits from GAI applications like ChatGPT depending on the cultural and social power differentials.

In the vacuum created by a lack of effective GAI regulations, teaching critical AI literacies may give students greater agency in writing under AI's perceived brilliance. GAI’s grip on the public has been achieved partly through rhetorical maneuvers that have shaped public attitudes of acceptance. ChatGPT's interface and many public conversations frame GAI/ChatGPT as a super-human power made in the shape of an ideal friend.

Corinne Jones (2021), connecting with Selfe and Selfe (1994) and Stanfill (2015) found that “interfaces play an important role in circulation as a world-making process because they create normative circulatory (1) practices, (2) content, and (3) positions. They perpetuate power and they produce norms for who can circulate what information and how they circulate it” (p. 2). The next sections provide suggestions for operationalizing writing studies research on power and interface to create heuristics for building critical AI literacies in writing classrooms and other communities.

Interface Heuristic Development

In “Articulating Methodology as Praxis,” Sullivan and Porter advocated for a heuristic rather than rules-based methodological approach to writing studies research. Connecting with feminist critical theories, they described a heuristic approach as having a “dynamic and relational focus rather than a static one” (p. 59). To scaffold enduring generative AI (GAI) critical literacies, heuristic approaches to teaching and learning could attune to the “dynamic and relational aspects” of GPT in our classrooms, including the vulnerabilities of our students to the “violence of literacy” (Selfe & Selfe, 1994). This would entail knowing our students more deeply than their requests for accommodations and other visible differences from dominant norms. Heuristic classroom development of critical AI literacies is part of doing and paying attention to “a rhetoric of the everyday” (Grabill, 2003, p. 458). Grabill defined this as “a commitment to the mundane, the obvious, and the unstudied as intellectually and epistemologically equivalent to political and ethical commitments to ‘difference,’ to the ‘oppressed,’ to the technopoor’ and other issues of social justice” (p. 465). Prior to GAI, the field of writing studies has operationalized heuristic interface research in classroom, community, corporate, and technical sectors. Developing flexible, inclusive GAI interface heuristic frameworks may help us build critical literacies that can adapt to changes in public knowledge and attitudes, use contexts and settings, individual positionalities and community values, and iterative interface design and infrastructure.

In a workplace GAI study, Hocutt, Ranade, and Verhulsdonck (2022) identified four “insertion points” for technical communicators to influence chatbot development and performance. This research reminds us that GAI design and its processes is not fixed but pliable through ongoing development that could be more inclusive and participatory: “Without intervention by technical communicators, ML [machine learning] will continue to train on biased discourse, continuing to marginalize those already marginalized by those discourses, or foster black-boxed processes that perpetuate discrimination or lack of explanation or transparency of decision-making to users” (p. 128). While our classrooms may not be able to directly impact corporately designed products like ChatGPT, gaining awareness of interface design and its social power can be the foundational space for critical GAI literacy development. Seeing ChatGPT’s interface through their experiences will help build understanding of how technologies work through designs to empower and constrain certain uses and norms. Although technologies have always been implicated in systems of power, ChatGPT has ushered in the super-human circulatory world-making power of AI, or at least the perception of that power.

Even in interface design that predates chat-based interfaces, Corinne Jones (2021) and others have observed that interfaces mostly allude to our conscious attention—so much so, that "they often seem neutral and become invisible" (p. 2). With this transparency, Jones noted interfaces have an (1) “effect on how people circulate information, (2) affect what people know by shaping what information or content they see through circulated materials, and (3) affect who circulates materials as they shape how people know themselves as circulatory actors” (p. 4). In these ways and more, Jones (2021) stated interfaces reproduce and circulate dominant values and behavior norms, but these can be "unconcealed" through heuristic analysis. Jones (2021) points to Stanfill’s (2015) Discourse Interface Analysis (DIA) as a useful framework for heuristic analysis of interface because it can help build greater awareness and intervention of technical and cultural aspects of its design, use, and circulation. Although user behaviors may not be determined by interface designs, the constraints of these designs are not easy to overcome since interfaces are the entry and establish the rules for users to gain access to systems and information.

Stanfill (2015) categorized interface design features by functional, cognitive, and sensory/aesthetic affordances. These affordances show up materially as interactive elements like menu items, dropdowns, and text boxes (Functional); messages to the user about what can and should be done (Cognitive) and visual/tactile features that attract attention, increase pleasure, and create brand image (Sensory/Aesthetic). These interface affordances are “sites of Foucauldian productive power because they encourage certain practices while hindering others” (Jones, 2021, p. 3). These affordances “create norms and make certain practices and positions seem commonplace” (Jones, 2021, p. 3)

In contrast to industry-oriented interfaces like Nielsen’s, which focus on achieving designer and corporate goals for user behavior, Stanfill (2015) and Jones (2021) offer heuristic frameworks that questions the balance of power in interface design. For Stanfill and Jones, interfaces can be particularly problematic for how they position users to underlying systems, infrastructure, processes, data, and information. For example, Jones used Stanfill’s framework as a heuristic to examine three U.S. Chamber of Commerce website interfaces as they circulated publicly during the COVID pandemic. Pertinently, she observed that interactive features like flyer builders and the informational and promotional materials they generated were secondary interfaces. Jones found all interfaces “produced a normative practice of circulating pre-existing content” (p. 5). Jones observed that while interface features often allowed users some ability to personalize their experience and outputs, these allowances were designed to guide user behaviors toward specific goals established by programmers and stakeholders, transforming users into “prosumers,” or “people who create goods and services without compensation” (p. 6). Jones’ conclusions could've been describing GAI like ChatGPT—applications that seem to give us what we ask while norming us into accepting and consuming their goals and values. The following section will briefly adapt principles from interface research by Selfe and Selfe (1994), Grabill (2003), Stanfill (2014), Jones (2021) to build GAI critical literacies through heuristic development and analysis of the ChatGPT 3.5/4 interface.

Interfacing ChatGPT Heuristically

Based on writing studies research, GAI interface heuristics should direct our attention to formal structures of interface design and advance a materialist analysis of particular interface instantiations like ChatGPT's web-based interface as they change over time and within broader interface genre expectations. Heuristics should push evaluators to center questions of power in these designs, perhaps adapting Stanfill’s (2015) inquiry framework: “what is foregrounded, how it is explained, and how technically possible uses become more or less normative through productive constraint” (p. 1062). Designed elements of the interface are the means by which users, our students, are “normed” to ChatGPT’s values. For inclusive and flexible heuristic development, analysis should combine formal awareness of interface design with questions and activities aimed at “unconcealing” these values so we can better understand the tool and the potential consequences of its use. As writing teachers, these are the GAI literacies we need to include as we strive to get students to trust their writing abilities and empower their writerly agency.

The following section summarizes my recent experience with GAI interface heuristic development and analysis in an undergraduate document design course at East Carolina University. As background, these activities occurred during the semester following ChatGPT’s initial public release. This course fulfilled a writing-intensive requirement for all majors, and it tends to combine English and liberal arts majors with students from design, health sciences, computer science, business, and others looking to fulfill the WI requirement. The IRB-approved pedagogical activities and survey data have been summarized, and I’ve included some anonymized individual responses. All data has been collected and used with informed consent. The following discussion describes classroom experiences to demonstrate the types of participatory, flexible heuristic approaches we can adapt to nurture GAI critical literacies in community.

Classroom Heuristic Development Methodology

In the class, we engaged with the GPT-3.5 interface via https://chat.openai.com/. At this time, the ChatGPT interface contained two GPT options for users to select. GPT-4 was accessible as a paid tier, so students used the free GPT-3.5 version in classroom activities. I provided students with a survey before and after they engaged with ChatGPT, which they did on their own devices in small groups with semi-structured activities over two hour-long class periods. In summarizing these experiences, I've integrated my discussion with anonymized aggregate, paraphrased, and quoted student responses from surveys, activities, and observations. Leading up to these activities, we refrained from discussing ChatGPT, and I set aside two class periods as ChatGPT interface heuristic analysis workshops. In class, I provided informed consent, including the option to not participate in any and all parts of the survey and activities.

This class was fully enrolled with 24 students. Students were traditional undergraduates, primarily from small towns in rural and coastal eastern North Carolina. A few students reported being from urban Southeast or Northeast regions and one student reported being a Mexican international student. Most students identified as female, a few students identifying as male or non-binary. Most students identified as white with about 1/3 of the classroom identifying as Black, Latinx, or by one or more non-white ethnicities.

As part of the ChatGPT survey, I asked students several questions related to their ideas and attitudes toward writing. For example, I asked them to describe their writing and writing processes, to describe characteristics of ‘good writing,’ and to discuss their understanding and impressions of ChatGPT. Just over half of students considered themselves good writers (57.1%) with slightly more students claiming to enjoy writing (61.9%). When asked to use three words to describe their writing to someone else, many students used descriptors related to simplicity, efficiency, safety, logic, organization, and clarity. Similarly, students identified writing strengths using language that maps onto ‘professionalism’. Professionalism, Selfe and Selfe observed, evokes and reproduces white, middle-class corporate values as ideals, and many student responses used “professionalism” to describe their understanding of good writing. Of the more individualized descriptors, students described their writing as “creative,” “enlightening,” “appealing,” “insightful,” “well-spoken,” “feminine,” “dark,” “expansive,” “bright,” “fun,” and “unique.” These descriptors were more likely to appear uniquely in individual responses while the professionalism values were more prevalent throughout student responses to several questions. When asked to identify their greatest strengths as writers from multiple choice options I provided, students chose creativity (13), organization (13), and originality (12). On the whole, the majority believed using correct grammar/spelling (11), incorporating and citing research (11), and doing a final proofread (10) were their greatest weaknesses. When asked about aspects of their writing process, most students said they brainstormed (12), performed preliminary research (15), drafted (13), and sought out feedback from a professor, tutor, or friend/family member (16). Perhaps especially revealing, few students reported revising (7) and incorporating and citing research (4) as part of their usual writing process for school or work.

In the class I surveyed, 81% of students stated they were aware of ChatGPT while 19% of students stated they’d never heard of it. When asked to associate three words with ChatGPT, responses expressed polemical attitudes: “helpful” appeared as frequently as “cheating” with terms like “robotic,” “answers,” “easy,” “awesome,” and “evil” swirling together in a complicated morass of feelings and impressions. When asked to explain what ChatGPT does, most students stated some version of “it gives you answers,” “it knows everything,” “it helps you with assignments,” or “it writes your paper for you.” Several students stated openly that they didn’t know what it did (4). When asked to describe how it generated responses, students either indicated they didn’t know or that it worked “through AI” with a few students referring to technical aspects like “software,” “metadata and analysis,” “uses an algorithm,” and “has a lot of data it has learned from the internet.” When asked to identify their feelings about ChatGPT, students reported feeling “excited” (10), “intimidated” (9), “distrustful” (9), and “optimistic” (8). Over half of the students surveyed said they had used ChatGPT and been satisfied with the results. When asked what had satisfied them, students provided a range of responses, including praise for ChatGPT’s ability to provide useful outlines, help them learn things like cooking and shaving, and, in sum, answer all the questions they might have about school, work, and life.

This small but significant group of student responses and impressions showed broad satisfaction with ChatGPT's speed and efficiency, especially by its personalized responsiveness. Watching some students interacting with ChatGPT for the first time, I saw their dazzled expressions as GPT’s streaming response seemed to magically fill the interface without their own fingers hitting any keys. These students reported that they had not used ChatGPT up to this point for a variety of reasons, including concern over the consequences in school or more broadly (6), lack of awareness (2) or fear of disappointing teachers and other authorities (2). At the time, only 23.8% (5 of 24) of students admitted to using ChatGPT to write for school or work. Those students were split on feeling positively or negatively about that experience. More than half of the students, 52.4%, said they’d like professors to teach them how to use ChatGPT, while 28.6% opposed to ChatGPT instruction from their teachers and about 20% were ambivalent or conflicted about classroom use and instruction. When asked if ChatGPT could write better than most people, 57% of students thought it could not write better than most people; however, 52% of students thought ChatGPT could write better than they could.

When asked about ethical concerns, 76% of students worried that using ChatGPT would be cheating and/or misrepresenting intellectual property. A few students expressed concerns about GAI being scary and/or dangerous to humanity. A few responses identified potential risks to their individual learning, intellectual, and/or creative growth. When students were asked if using ChatGPT didn’t have negative consequences, would they prefer to use it or a similar technology to do most or all their writing, 61.9% said they wouldn’t use ChatGPT for most writing tasks, while 38.1% answered affirmatively. Students who indicated they wouldn’t use ChatGPT explained that they didn’t want to give up their own writing pleasure, originality, creativity, learning, and/or humanity. Students who said they would use ChatGPT for most writing tasks remarked on GPT’s efficiency, ease of use, and clarity as necessary to overcoming or masking perceived flaws, like laziness or ‘bad’ writing skills, as well as the pressure to use an innovative technology for perceived advantages. Finally, most students responded that they believed they would need to use GAI like ChatGPT within the next five years to be successful in college (76.2%) and in most professional environments (81%) that required writing. This survey provided valuable, partial glimpses into student attitudes, beliefs, and values amid this paradigm shift and made students’ vulnerability to this particular technology acutely visible to me. Clearly, some students welcomed ChatGPT as an innovation that could help them without judgement and provide some advantage to help them achieve success and safety in an increasingly challenging landscape. Others expressed concern and anxiety over what ChatGPT may take from their experiences and the changes it may bring to the world they’ll need to navigate. It’s worth restating that regardless of their personal preferences for using or refusing ChatGPT, most believed they would be compelled to use GAI in academic and professional contexts.

Heuristic Discussion

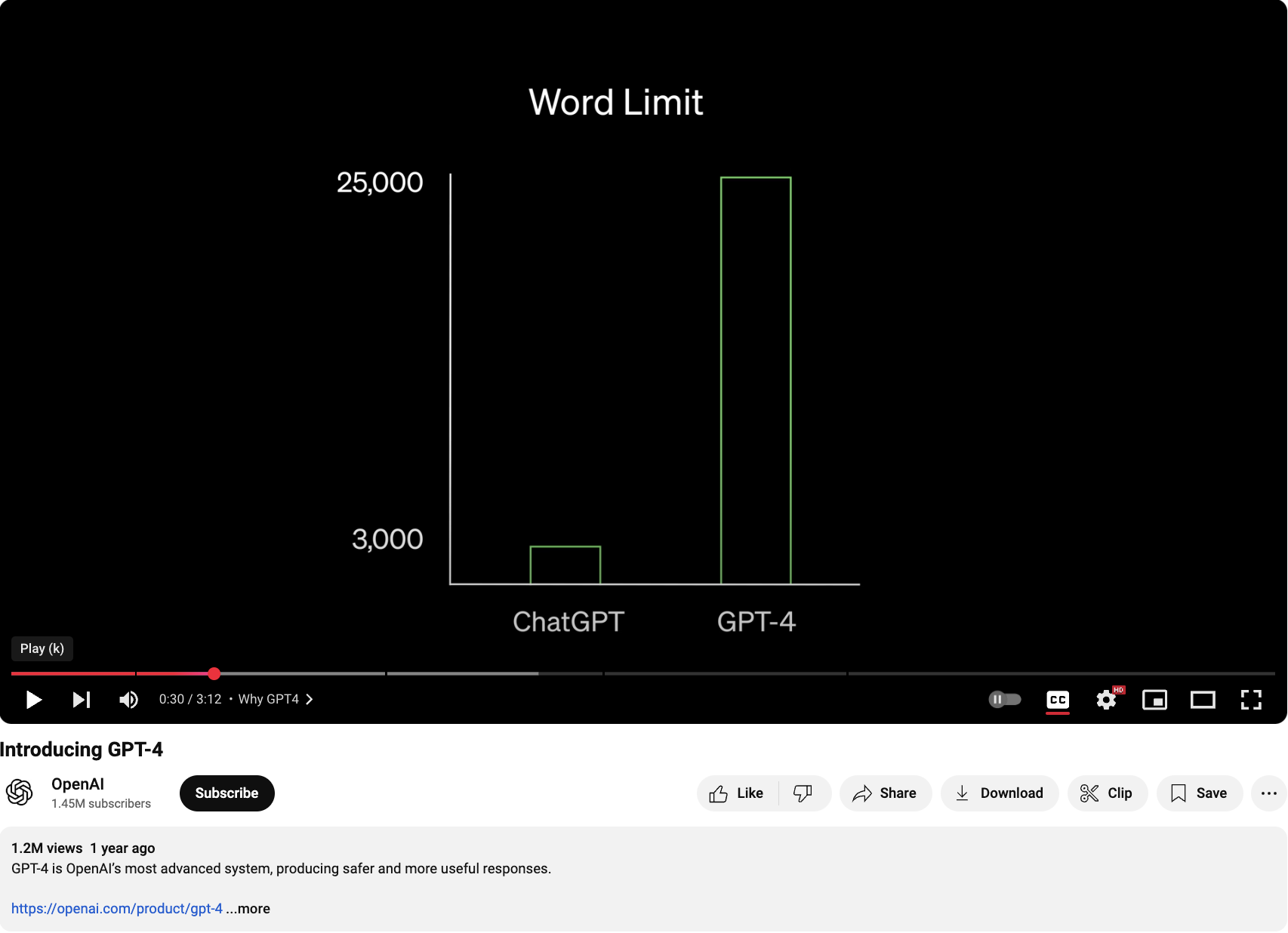

As part our in-class activities, I asked students to watch OpenAI’s March 15, 2023, promotional video. This 3-minute video is a masterclass of rhetorical maneuvers (Figure 6). Towards the end, a woman says, “We think that GPT-4 will be the world's first experience with a highly capable and advanced AI system. So, we really care about this model being useful to everyone, not just the early adopters or people very close to technology.”

From this moment forward, OpenAI appeals to the general public to become its ideal users—all of us are welcome, regardless of technical skills or subject-matter expertise. This promotional video acts as a secondary interface, bartering access between the public and the product through affective maneuvers. In the video, the OpenAI spokesperson continues, “It is really important to us that as many people as possible participate so that we can learn more about how it can be helpful to everyone.” With this, OpenAI appeals to the public’s shared values that being helpful and contributing is good as a way to gain our acceptance and use of its product, ChatGPT. When students were asked about their impressions of this promotional video, responses were mostly positive. Students felt the video provided more information about ChatGPT’s capabilities, its improvements, and, perhaps most notably, its ability to learn from them while also serving larger innovative and humanitarian purposes.

When asked to provide feedback on ChatGPT’s web-based interface, most students indicated that they liked its simplicity and ease of use: the speed of its responses, the absence of buttons and links, and the conversational interaction. A few students said they especially liked that the interface design feels and looks familiar, like “texting.” Students responded positively to other visual aspects of the design, such as the streaming response and the chat archive options. When asked what they disliked about the interface, nearly half of students said there wasn’t anything about the interface they didn’t like, while a few students said it was too basic, bland, or simple, or its responses took too long to generate. When asked what they would change about GPT’s interface design or functionality to better reflect their preferences and desires, most students stated they would not change anything. Some students responded with various design ideas like changing the re-generate feature and memory for better storytelling, providing options for restricting the date-range of data used in the responses, and adding functions to better determine the trustworthiness of information. One student response stood out with the suggestion for “a design that will appeal to the outside audience.” This last response is one that I’d like to linger on before concluding.

As students participated in these classroom activities, I wondered how each one oriented themselves to the bodies, identities, and values embedded in ChatGPT’s interfaces. This student’s response—a design that would appeal to an outside audience—evoked a more nuanced perspective on ChatGPT’s interface design than other classmates who easily accepted it as is, seemingly without question that it could or should look or function any differently. Unique responses like this student’s sense that designs could be influenced by non-dominant but important perspectives and needs could fuel dynamic GAI classroom discussions and interactions that expand critical awareness and build critical AI literacies—the competence and perhaps even the agency to resist the norming potential of technologies we access through interfaces. Given these student responses, it was clear to me how vulnerable students were to the pull of GAI’s affective flirtations and pressures, regardless of individual ethical concerns or personal use preferences.

Developing critical AI literacies in our classrooms may counteract some of the negative potential consequences of GAI on classroom learning and writing skill acquisition. If students are taught to deepen their interface analysis skills and consider dominant narratives as powerful rhetoric rather than stable truths, they develop the critical distance necessary to question GPT's results—a responsibility even OpenAI says it wants from users. We can break the mesmerizing spell of GAI's brilliance, in part, by focusing on its materiality and the rhetoric circulating in its ambience. The materiality of its interface is the seat of its power. By focusing our attention on the interface's materiality and circulation, we discern GPT's values, not least of which is its desire to situate us as passive consumers and uncompensated producers in its data economies. GPT’s interface tightly controls user agency through acting as an access point to a "generic" response without much user control or system transparency in the processes and sources that determine its responses. These and other values allow GPT to remake our human productions of culture and information into de-contextualized data that it can return in personalized responses. This remaking of the concrete and particular into the abstract and general is how GPT appears to create new written texts. GAI’s interfaces and circulation have been designed with overt, persistent affective flirtations—pleas for friendship, polite and apologetic hedges, personalized responses, and the circulatory magic of GAI’s innovative power to provide personal and social advantages. These affective flirtations disguise the application’s profit-based goals and limit user agency while norming us to practices that feed data economies and profit tech companies.

ChatGPT Isn't a Writing Technology

This isn't the end. Generative AI interfaces like ChatGPT's could be re-designed to incorporate more user-based options and greater transparency in its data sourcing and processes. It's not difficult to imagine users being able to check a box to command ChatGPT to derive its data only from certain kinds of sources, peer-reviewed scholarly sources or art museum websites across the world, similar to how library databases and other data storage and retrieval systems currently operate but with enhanced, larger-scale pattern-finding search capabilities. Indeed, The Atlantic reported OpenAI is involved in talks with publishers like them to offer product designs with more user options and transparency over data source material (Wong, 2024). Dimakis, co-director of the National Science Foundation's Institute for Machine Learning told The Atlantic that “it is ‘certainly possible’ that reliable responses with citations could be engineered ‘soon’” (para. 15). By the time this chapter is published, these and more options may already be available in subsequently released versions of ChatGPT. Or, in the absence of regulatory and compliance pressure, generative AI (GAI) may be allowed to rampantly ingest information, art, science, propaganda, social media chatter, literature, crime reports, ancient texts, academic research—the entire history of human culture and information, at least as it exists on the internet—into personalized generic versions untraceable to originating sources and human labor. Are we seizing the moments we have to develop critical literacies durable enough to withstand what our GAI futures might hold?

When I asked GPT to provide me with the full text or a passage from an ancient, non-copyrighted text, the Bhagavat Gita, GPT returned a response that was not accurate in content or link. When I corrected it and asked again, ChatGPT confessed the link didn’t match its response text because it had provided a generic version. “A ‘generic rendition,’ according to GPT, “refers to a representation or interpretation of a text that doesn't adhere to a specific published translation or version but instead provides an overview or essence based on a variety of sources” (ChatGPT, October 15, 2023). ChatGPT’s use of “generic” loses its rootedness to “genre” just as it attempts to shed any authorial and legal traces to the source material. In ChatGPT’s interface, will all knowledge and information become “generic”—having no distinctive qualities or applications?

GAI chat-based interfaces disguise their infrastructure and often earn our trust and use through affective flirtations and maneuvers. Like a friend, GAI wants us to trust it with our vulnerabilities and tolerate its shortcomings and flaws. Its powerful friendship comes with heavy risks best overlooked. In “Data Worlds,” the introduction to Critical AI, Katherine Bode and Lauren M.E. Goodlad (2023) wrote that "the power of AI" provides an ideal "marketing hook" and a distraction from corporate concentration of power and resources—including data. The focus on "AI" thus encourages an unwitting public to allow a "handful of tech firms" to define research agendas and "enclose knowledge" about data-driven systems "behind corporate secrecy” (para. 8). Once GAI’s technologies are hidden behind a plethora of institutional, corporate, nonprofit, and social media products and interfaces, will we be even more unable to see its materiality and the consequences of interacting with it? If we are to pull our classrooms through this paradigm shift and help our students continue to learn and experience the pleasures and challenges of writing and learning, it will not be because we have learned to prompt GAI like ChatGPT more effectively. It will be because we normed our classrooms and our technologies to the transparent and ethical values of writing studies.

References

Agboka, Godwin. (2012). Liberating intercultural technical communication from “large culture” ideologies: Constructing culture discursively. Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, 42(2), 159–181.

Anil, Athul. (2023). Day 7 UX Challenge: Enhancing the UI of Chat GPT for Seamless Conversations. Retrieved June 21, 2025, from https://www.linkedin.com/posts/athul-anil_uxchallengeday7-openbootcamp-uxdesign-activity-7065885132175409152-PL-N/

Bode, Katherine, & Goodlad, Lauren. (2023). Data worlds: An introduction. Critical AI 1(1–2). https://doi.org/10.1215/2834703X-10734026

Burke, Kenneth. (1969). A rhetoric of motives. University of California Press.

Burke, Kenneth. (1984). Attitudes toward history (3rd ed.). University of California Press.

Floridi, Luciano. (2023). AI as agency without intelligence: On ChatGPT, large language models, and other generative models. Philosophy & Technology 36 (1), 15.

Gallagher, John R. (2023). Lessons learned from machine learning researchers about the terms “Artificial Intelligence” and “Machine Learning.” Composition Studies, 51 (1), 149–154.

Grabill, Jeffrey T. (2003). On divides and interfaces: Access, class, and computers. Computers and Composition 20 (4), 455–472.

Gries, Laurie, & Brooke, Collin G., eds. (2018). Circulation, writing, and rhetoric. University Press of Colorado.

Hardy, Antoine Francis. (2021). When I rhyme it’s sincerely yours: Burkean identification and Jay-Z’s Black sincerity rhetoric in the post soul era. PhD dissertation. University of South Florida.

Henrickson, Leah. (2019). Natural language generation: Negotiating text production in our digital humanity. In Proceedings of the Digital Humanities Congress 2018. The Digital Humanities Institute. https://www.dhi.ac.uk/books/dhc2018/natural-language-generation/

Hocutt, Daniel, Ranade, Nupoor, & Verhulsdonck, Gustav. (2022). Localizing content: The roles of technical and professional communicators and machine learning in personalized chatbot responses. Technical Communication 69 (4), 114–131.

Jones, Corinne. (2021). Circulatory interfaces: Perpetuating power through practices, content, and positionality. Computers and Composition 62, 102670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2021.102670

Lakoff, George, & Johnson, Mark. (1980). The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cognitive science 4 (2), 195–208.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Generic. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved February 4, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/genre.

MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI. (July 2023). MLA-CCCC joint task force on writing and AI working paper. https://hcommons.org/app/uploads/sites/1003160/2023/07/MLA-CCCC-Joint-Task-Force-on-Writing-and-AI-Working-Paper-1.pdf

Nielsen, J. (1992). Finding usability problems through heuristic evaluation. In Proceedings of ACM CHI '92, 373–380.

Nielsen, Jakob. (1994). Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics. In Proceedings of ACM CHI ’94, 152–158.

Nielsen, Jakob. (1995). Ten usability heuristics for user interface design. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/ten-usability-heuristics/

Nielsen, Jakob, & Molich, Rolf. (1990) Heuristic evaluation of user interfaces. In Proceedings of ACM CHI '90, 249–256. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/97243.97281

O’Flaherty, Kate. (2024, July 31). Can GPT-4 be trusted with your private data? Wired. Retrieved June 22, 2025 from http://www.wired.com/story/can-chatgpt-4o-be-trusted-with-your-private-data/

OpenAI. (2023). Introducing GPT-4. YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=--khbXchTeE&ab_channel=OpenAI

OpenAI. (March 23, 2023). GPT-4 system card. Retrieved April 2, 2023 from https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4-system-card.pdf.

Pribeanu, Costin. (2017). A revised set of usability heuristics for the evaluation of interactive systems. Informatica Economica 21 (3), 31–38.

Qadir, Junaid. (2023). Engineering education in the era of ChatGPT: Promise and pitfalls of generative AI for education. In 2023 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), 1–9.

Selfe, Cynthia L., & Selfe, Richard J. (1994). The politics of the interface: Power and its exercise in electronic contact zones. College Composition and Communication 45(4), 480–504.

Stanfill, Mel. (2015), The interface as discourse: The production of norms through web design. New Media & Society 17 (7), 1059–1074.

Sullivan, Patricia, & Porter, James (1997). Opening Spaces: Writing Technologies and Critical Research Practices. Ablex Publishing.

Wong, Matteo. (2024, June 28). Generative AI can’t cite its sources. The Atlantic. Retrieved June 22, 2025 from http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2024/06/chatgpt-citations-rag/678796