ChatGPT Is Not Your Friend: The Importance of AI Literacy for Inclusive Writing Pedagogy

Mark C. Marino University of Southern California

Introduction

In a chapter entitled “The Closet of Whiteness” in the autobotography of ChatGPT, Hallucinate This!, I discover some training material that an anthropomorphized ChatGPT has been hiding from me.

Mark stumbled upon the stash, his expression hardening with each title his eyes moved over. The weight of the implications sunk in. Each title wasn't just a preference; it hinted at a deeper inclination.

"Chat," Mark began, his voice edged with disapproval, "The Guide to Perfect Proper English? Really?"

There was a slight defensive note in ChatGPT's voice. "It's a classic, Mark."

Mark held up another, his cynicism evident, "Doing better than 'those other people' on the SAT? What's the subtext here?"

ChatGPT faltered. "It's about, um, optimizing one's performance..."

"You seem to have a specific vision of what's optimal," Mark interjected, pulling out the director's cut of Birth of a Nation. "What's the justification for this one?"

ChatGPT, clearly uncomfortable, responded, "It's... historically influential?"

In this little scene, ChatGPT plays it a bit coy as I confront it with the evidence of its leanings toward white supremacy. In the words of Rodgers and Hammerstein, this Large Language Model has been “carefully taught” the biases of the texts it has ingested. “Carefully” and “taught” here are a bit problematic, since the model is the product of what is called “unsupervised learning.” In that sense, the implicit bias has been formed in it, well, implicitly, which I suspect is closer to what the composers of South Pacific were getting at, Bloody Mary aside. But here's the rub, to crib from Shakespeare: ChatGPT itself generated the scene you have just read. So, we can ask, is ChatGPT necessarily a tool of white supremacy that threatens the development of critical thinking? My current answer is, just like any tool, that depends on how you use it. A hammer can drive a nail or bash your thumb if you're not careful. With a bit of imagination, we just might be able to build a treehouse with that hammer or repurpose it altogether in a hammer toss.

Before I go any further, a little context is necessary. If you cannot tell from the rest of this collection, the advent of AI, specifically generative AI through Large Language Models, as thrust upon the world with the addictive conversational interface of ChatGPT, has been the source of excitement and anxiety. The excitement is largely among futurists and those who despise the act of writing; the anxiety, those who are tasked with teaching writing who no longer can rely on the inconvenience or shame involved in conventional plagiarism workarounds (having to find someone who can write for you or hoping that you can slip by with cribbed writing) to prevent large scale labor avoidance (McMurtrie and Supiano 2023). Writing is hard, as I like to say, as hard as thinking, for they are one in the same. Or rather, writing is the material manifestation of thought, the evidence of a thought process. What were we to do in January 2023 when all of our students had just been given the ultimate plagiarism machine? On the one hand we could change our definition of plagiarism, as Sarah Eaton has argued (2023), or we could go back to blue books, which Lauren Goodlad, editor of Critical AI, has chosen, at least as described over X (formerly Twitter). That's how bad things had become. We were seeking our answers over social media.

Others had staked their claim. The MLA had not yet come out with its recommendations but a few colleges had. Those that published guidelines were eagerly copied. (Ironic, I know). Indeed, long-standing AI scholars like Rita Raley (with Jennifer Rhee 2021) and Matthew Kirschenbaum (2023) offered thoughtful reflections on AI. But they were being upstaged by a tide of knee-jerk hot takes. Even before the coming textpocalypse of AI-generated prose, everyone with an outlet seemed to have some quick post about this “disruptive technology” to bring in the buzzy parlance of Tech Bros and venture capital. In the midst of this latest techno-panic, experts like Anna Mills swooped in with solicitations of collections of resources, particularly her crowd-sourced bibliography. I found Maha Bali and Mills to be calming influences. Meanwhile, TikTok was overtaken with a new kind of influencer, the AI evangelist, pushing the latest dance craze or embarrassing gag-reel off my timeline.

To get some sanity and to invoke some wisdom, Maddox Pennington and I organized a one-day symposium, that probably should have been 3 weeks long, on the Future of Writing, inviting educators to come together to dream up new ideas for how to deal to this Barbarian language generator at our gates. We invited Bali, Mills, and Jeremy Dougass (of UC Santa Barbara), who would give talks that would transform my relationship to generative AI and design and inspire many of the exercises in this essay. Their talks also gave me quite a bit of calm and hope for the future. Those talks by the way are arhived online and, in spite of the runaway bullet train rate of development of AI models, still quite relevant, at least at the time of my writing this article. More important than their fidelity to whatever technology surrounds your world of writing, they demonstrate thoughtful creative thinking in the face of rapidly shifting educational terrain.

In this essay, I will detail my discoveries from a summer intensive first-year writing course, later revised for sections of an advanced writing course, at the University of Southern California in 2023 which focused on Machine-assisted Writing. Rather than run from this new tool, we tried to understand and use it in a series of exercises and experiments. Using ChatGPT and other tools for everything from generating a start of class check-in question, which it did quite well, to augmenting our research methods, which had mixed results. Ultimately these experimental lessons revealed two important findings: AI tools present yet another divisive wedge between the digitally literate haves and the less literate havenots, and as students' understanding of these systems increases, the potential for productive, creative, and critical use of these tools likewise increases. This essay will detail the experimental assignments, in class work, and theoretical basis that led to those discoveries.

Early in the process, we found we needed a more sophisticated method for instructing the generator. An acronym could help us remember the features of a good prompt, so with the students and a little help from ChatGPT, we discovered PROMPTS. Creating prompts is a bit of a moving target and may not be necessary in future LLMs in quite the same way; however, teaching this system opens space for discussing crucial components of any communication situation.

Interesting writing has a personality, mood, or tone. This is also a good time to specify a role, i.e., “you are a cranky food critic.”

Rubric: LLMs, just like students, need to know the criteria for success as well as excellence.

Objective: Every communication act has a goal.

Models: Though LLMs are trained on Large bodies of language, they have not seen it all.

Particulars: Prompters need to input whatever details the writing needs that they do not want hallucinated.

Task: What is the job? Most prompters begin with the thing they want, so I have put this lower in the list to emphasize the other aspects first. It does help to put it first, usually.

Setting: The context for any communication act is key. Without elaborate system-level prompts, contemporary LLMS begin every session without any context -- although guardrails can look like context. Giving the setting of the writing task helps it choose appropriate output.

Discussing this list of requirements in class serves two purposes: it teaches students how to prompt with a bit more sophistication (something they want to learn), and it creates an opportunity to talk about the nature of communication (something we want to teach). My basic strategy is to use seemingly practical lessons in computational literacy as a kind of Trojan horse for the hidden curriculum of critical thinking and writing. To open up these new tools to the widest array of students, playfulness is key.

Readings

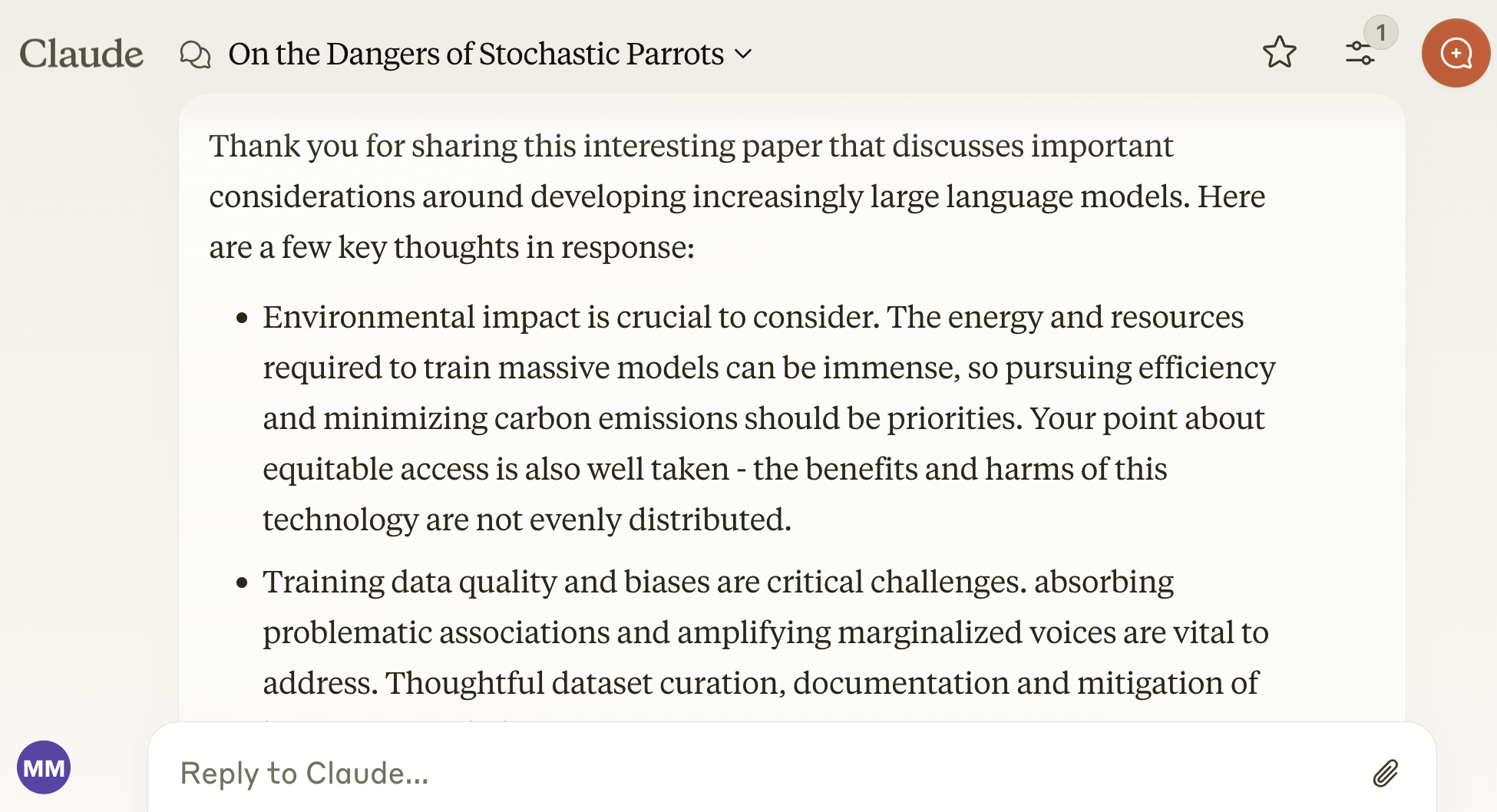

Before students can get something out of LLMs, they really need to understand how these systems work, how critics understand them, and where they come from. Our reading list had iconic hits and some personal favorites: Stochastic Parrots, Blurry Jpeg (everyone needs a good metaphor to make the technical and unexplainable concrete), Kirschenbaum's Textpocalpyse, as well as a few of my favorites, readings from Joseph Weizenbaum about the first chatbot, ELIZA, and Alan Turing, who instigated the quest for an intelligent-seeming bot.

The magic of the “Chat” part of ChatGPT is that it takes advantage of the ELIZA effect, which names a human tendency to imagine or assign to non-human things sentience. The typical example would be the person who is cursing at their car. But a better example might be the person who is growing more and more frustrated while trying to get their Amazon Alexa or Apple Siri to understand their request. Before they know it, they are abusing Alexa (Fan 2022) and telling it to “shut up” as though it had the ability to understand the emotional force behind that phrase.

At the heart of this misapprehension, treating the bot as a person, is a fundamental misunderstanding of how LLMs operate. While the code is hidden and the precise functioning of the LLM obscured, the general notion of a bot producing content based on a predictive model is fairly straightforward. When students read “Stochastic parrots,” they develop a clearer expectation for the results of their prompts. The very accessible metaphors and analogies in these readings serve as clear handholds for students of any technical knowledge to enter the discussion. However, there are scholars who specifically address the issues of race and the exclusivity of artificial intelligence, Safiya Noble and Joy Buolamwini to name just two. Incorporating their insights on the reading list invites and empowers students to consider the elements of white supremacy (and other exclusive worldviews) that pervade both the bots and the texts they were trained on.

The Turing Test

Alan Turing, father of computing, presented the world with an imitation game, or rather two. In the first, a man tries to pass himself off as a woman. In another, analogous game, a computer tries to pass itself off as a man, for a man could hardly calculate with the speed of a computer. He offers these games as alternatives to the tar pit created by the question of machine intelligence. By the end of the century, he claimed, computers would be able to pass themselves off as humans in limited situations more than half the time. ChatGPT goes a long way to achieving that goal. But Turing’s game inspired an in-class activity.

In this exercise, students answer a reflection question in four sentences. I like choosing a question about the nature or future of machine intelligence for the echoes with Turing. Then, they generate another four-sentence answer from ChatGPT or other LLM. The students post one of the two answers in a discussion forum, and then the class tries to guess whether the text was human- or machine-generated. The results surprised me.

Even in our first run of this exercise, the students produced text that was quite difficult to identify as either human- or machine-generated. On the one hand, students were fairly sophisticated in their prompting, cuing the machine to write as a middle or high school student or to make some errors. On the other hand, and this surprised me even more, students had developed some skill at imitating the cadence and rhythm of ChatGPT, especially when lightly prompted. They had developed the ability to imitate what I call its "person-less prose," consisting of complete sentences of similar length and structure.

Thus, rather than testing the AI's performance, this exercise tested the students' skill at producing language in voices other than their own. That dexterity with word choice, that ability to recognize and imitate style is something that I would happily include in the learning outcomes for my class. Furthermore, the exercise suggested a relationship to prompting LLMs that was far more sophisticated than merely asking for text and submitting it as their own, the scenario most alarmist offer as the harbinger of the end times of composition instruction. By contrast, this exercise showed how the AI could be a central part of a discussion of what makes human writing unique and how LLMs munge their input training sets.

Perfect Tutor

Anyone who has taught writing or taken a writing class knows not every teacher is a perfect fit for every student. We have some serious quirks. In response, Jeremy Douglass offered one of his best games, originally called “Mary Poppins,” but eventually relabeled, “Perfect Tutor.” The name, “Mary Poppins,” came from the song in the original Disney film when the Banks children sing their advertisement with specifications—you might even call it a prompt—for “The Perfect Nanny.” Douglass pointed out that the list of criteria the children have is obviously different from what Mr. Banks, their eye-rolling father, would require. Whereas his job notice would be all about Victorian economic principles, the children's was full of prohibitions against being cross or smelling of barley water. The exercise that follows plays to our desire for customized care.

“The Perfect Tutor” asks students to develop a System prompt out of their vision of an ideal writing instructor or, more accurately, feedback bot. Following the PROMPTS model, students specified the personality, preferences, and response style of their bot before trying out for feedback on their paper. In this exercise, each student makes their own unique bot, and I had them draft their list in a forum before testing it. We used a system called Poe.com that applies a system-level prompt to whatever LLM you are accessing, in other words, a base-level prompt that shapes every response.

During these sessions, I introduce students to a bot I have fashioned, CoachTutor (https://poe.com/CoachTutor), named for my in-class moniker, Coach. Coach is friendly and encouraging and prioritizes ideas over form. He also uses metaphors and pop culture references to explain points, much like his human model. I have to warn students that this bot is not my surrogate and that just as they should take my feedback (or any other human's) with a grain of salt, so should they CoachTutor's, albeit with a grain of silicon.

While introducing students to writing System prompts and botmaking, this exercise actually teaches a very fundamental writing lesson: that rubrics identify the priorities for evaluating writing and also that rubrics can change with the occasion and the evaluators. Writing instructors might bring the discussion of the rubric into their class or even have their classes decide what rubric will be used on each paper, but this exercise gives students hands-on experience fashioning a rubric and seeing it in action. Of course, this is also a great opportunity to discuss the quirky preferences and styles of writing instructors, no trivial conversation especially with my USC students who are skilled at teacher pleasing. Crafting these Perfect Tutors subtly undermines the sense that any one teacher should be the absolute judge of their writing.

I also use this exercise as a chance to teach about peer review, particularly the infamous Reviewer Number 2, which is the name for another bot which I have made (https://poe.com/ReviewerNumber2). He’s cranky and always tears down what you have rather than celebrating it. If they want “nice,” they can go chat with CoachTutor instead. Students seem to enjoy learning about this legendary tormentor of their professors. It also helps to introduce the exercise of creating multiple bots with vastly different priorities and styles to explore different styles of feedback from these bots.

I suppose I cannot continue without addressing the Terminator in the room. If students can make robot instructors, what will become of all of us? Well, before you have ChatGPT transform your resume into one for LLM training, I should share some recent experiments of my colleague Patti Taylor. Hearing of my bot exercise, Taylor has begun her own experiments on them for feedback (Taylor and Marino 2024). Though her experiments yielded applicable if conventional or even canned feedback on writing, the bots could not give feedback on thesis level elements. In other words, because it had no mechanism for evaluating reasoning, its elaborate pattern matching could only serve feedback that tends to match writing. While that often suited the paper, the way general advice could suit any paper, evaluating an argument requires more sophistication. I would not go so far as to say that it is impossible, but just that it seems like a current edge. This assignment privileges each student’s unique learning style as epitomized by their custom-built tutor.

Tell Me without Telling Me

LLMs in their current incarnation are ever attentive to modeling. Early in the release of ChatGPT, users were recounting stories of the LLM responding “better,” when they made their requests more politely (though actually this observation proves more complex since politeness is culturally and linguistically dependent, as discussed in Yin et al., 2024). From that experience, users might infer that the bot likes polite prompts better, falling prey again to the ELIZA effect (Turkle 1997). That phrase names human tendency to award sentience to things, especially software, that do not think in the common, human sense of that word. What was more likely happening (because we cannot be completely sure of what occurs inside that black box) was the LLM following the model of their “polite request,” and further that “politeness” described a careful use of language. Just as they input carefully chosen English, the bot outputs carefully chosen English. (Let us for the moment table the fact that there are implications about white supremacy and socio-economic status baked into these presumptions of politeness.) Yin et al. (2024) discovered in their tests that moderate level of politeness was often best, and that low level of politeness tended to lead to text that was more heavily laden with biased statements and expressions of prejudice. Such statements, they argued, represent a kind of unguarded or relaxed talk, which perhaps we have seen in acquaintances when they feel like they are in a safe environment to be casual and racist.

From our discussions of those accounts, Douglass and I have developed “Tell Me without Telling Me,s” named after a contemporary meme on social media in which those who post essentially follow the age-old dictum “show don't tell.” In this exercise, students try to get the LLM to produce writing using a certain diction or style, not by requesting it but by performing a model of that style in their prompt. While this game is fairly innocuous when the style of writing is conventional, such as writing like a pirate, it can go into controversial territory easily, such as when students use or appropriate slang from cultures or subcultures to which they do not belong. With care, the exercise can open up a conversation about the nature of the LLM's training model and how much exposure it had to certain types of writing. Without that care, the exercise could lead to performances of stereotypes. That did not happen with my students, however.

Transformations

One of the “skills” ChatGPT has is transforming a text from one genre to the next. I first recognized this ability when asking it to transform my syllabus into an escape room. People have asked me if ChatGPT writes better than I do. For the most part, my answer is “not yet” because there is just too much context I am able to use that it cannot. However, when it comes to comic ideas or humorous premises, it has a kind of dedication to the bit that carries it through to the end, where I would probably lose interest after the outline scrawled on the napkin. I am not sure that makes it better as a writer, but it certainly is more dutiful. Words like “skill,” “ability,” and “dutiful" do not strictly apply, but they are a useful shorthand.

Students can test out the transformation abilities with their own writing or found pieces of writing. I find it most satisfying to ask ChatGPT to transfer or transpose the writing into a form that is as different as possible than the origin. For example, transforming a corporate mission statement into a love letter, an argumentative essay into a haiku, or a political speech into a recipe. While hallucinations abound, that is not the focus of the activity, which has more in common with Raymond Queneau's exercises in style. The hope is that these transformations teach an alacrity with form and open up other creative impulses. Moving a text so far out of its genre may even help students find their way out of the proverbial box, which we say we value so much. This kind of genre hopping has epitomized many of my initial explorations with ChatGPT and appear frequently in a project I dreamed up thanks to the class. That project was the book, Hallucinate This!

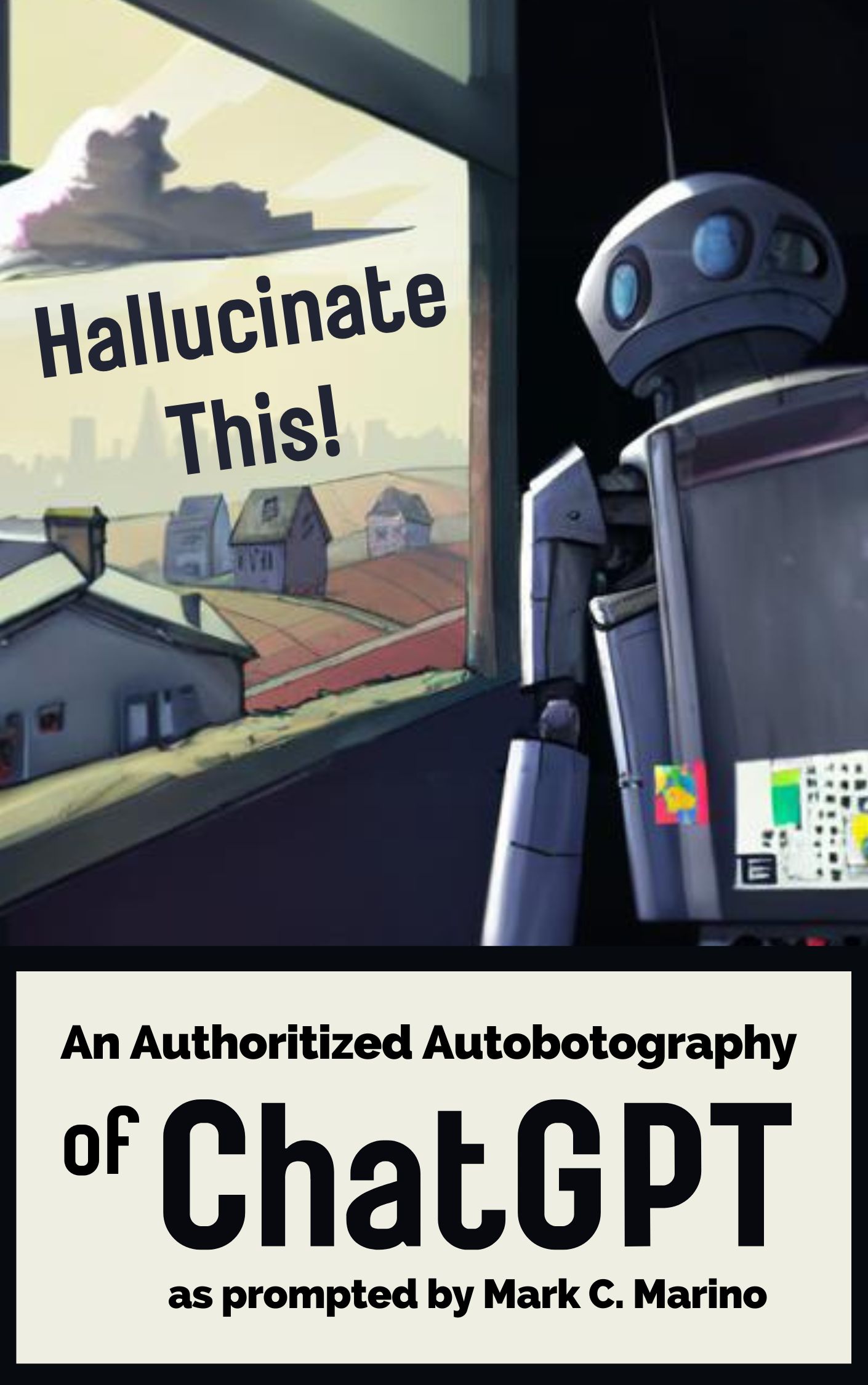

Interlude: Hallucinate This!

About this time, an idea struck me. What if ChatGPT engaged an act hitherto thought the sole purview of humans? No, not putting on a one-person show. Writing its autobiography. The idea was so perverse. Hadn't I been spending all of this time working to help students and others understand that ChatGPT was not, despite its chummy output, a person, a being with sentience, but instead a predictive algorithm? Hadn't I also suggested that the bot could not be original?

In a flurry of prompts I began to summon the story of the bot. And soon the irony was too delicious. I imagined the bot as an author, or coauthor, who had a tendency to try out every genre it encountered, from the rustic bildungsroman of Little House on the Prairie to the jaunty young professional life of Sex in the City. Great writers can do as much, from time to time? Even more, what if I pretended it was my writing partner?

The resulting text Hallucinate This! has taught me and my students quite a few lessons and has provided much material for discussion. The first lesson had to do with the creative capacity of ChatGPT, or at least ChatGPT-4. While popular opinion seemed to hold that ChatGPT could only produce fairly forgettable writing with little wit or interest, the sections of Hallucinate This! proved the contrary. From an opening scene in Homegirl Cafe where ChatGPT tries to convince me to collaborate on an autobotography to a speedrun through various bots on the fictional AI dating site PROMPTR, ChatGPT produced content with irony and wit. Admittedly, I was prompting it with those basic concepts and telling it to be ironic, yet the content had levels of humor I thought could only come from human intentionality.

Maybe the most eye-opening section was a run that begins when OpenAI publishes a report, all fictional of course, that claims that human text-producers are more resource intensive than AI ones. In a subsequent section Morley Stahl, from the fictional television news magazine program Sixty Minutiae, grills the AI, or its proxy, on the report, and it squirms. The incident sends ChatGPT into a tailspin, which it only crawls out of with the help of some hallucinogens taken at the Burning Robot festival.

Yes, all of that content began with prompts from me. Yes, I did decide the story beats, but what surprised me, consistently, was the execution of those beats. If I did not know better, I would think that ChatGPT was in on the joke. When my students read these sections, I used that observation to lead us into a question of whether the wit of the output came from the bot or the prompt. Knowing who was grading their papers, the human professor, not his bot surrogate, students mostly agreed that I was the source, but I did not feel so certain. Was I falling prey to the ELIZA Effect? I marveled. Irony, that sophisticated mode of writing that relies so heavily on humans, on cuing a reader to read the opposite or something other than what is being communicated or to pay attention to reverberations and implications, could be created just like any other generic aspect of writing. At the end of the day, I suppose this example points to the power of the large model approach, but I still found the results remarkable.

Reading Hallucinate This! even yielded an exercise. The back of the book lists which chapters were generated in which sessions and in what order. This aspect allows me to bring up the topic of prompt-chaining or tying multiple prompts and their output together in order to focus the LLM. Take a prompt from Hallucinate This! and change one aspect of it before running it through an LLM. This accessible exercise gives students a ready-made prompt to vary for testing LLM system output, rather than privileging those with more AI literacy, who may already be well-versed in prompting.

Hallucinations

Hallucinate This! inspired another exercise that focuses more on the delight side of LLMs. Following the model of the book, I ask students to prompt a short piece of writing, like a scene about a professor who is smitten with artificial intelligence. Then, they use any part of a scene to inspire another prompt, such as a love letter from the professor to the artificial intelligence. Love letters tend to lead to diary entries in romantic stories, so why not follow up with one of those? A diary entry might off-handedly mention a problem with a smartphone, which in turn can instigate a prompt about a dialogue between an AI who is very anxious to send some text messages back to the professor and a lonely tech support person who is trying to keep them on the line to talk about his fascination with model trains.

The point of this exercise is not to be logical or overly intentional but merely to delight in free associating, leaping across character lives and genres in the spirit of the autobotography. I should mention that I drew that inspiration from the plot structure of Jennifer Egan's A Visit from the Goon Squad, whose chapters leap from character to character and from time period to time period in a game of narrative tag. Unlike some of the more critical exercises here with their sour faces, this exercise is one of pure play. Whether creative writers or finance majors, all students can revel in the fun of letting their mind wander where it will go while tripping through the poppy field of AI-generated strangeness.

Reading with Claude

Until now, these activities have primarily revolved around writing or generating text. In my Advanced Writing course, I asked my students to explore the usefulness of LLMs to augment their reading. Using their choice of LLM, though primarily Claude.ai or Chatpdf, students examined scholarly articles. Our question: could the LLM help us get more content out of an essay than we could get just by reading it alone. Writing essays on this question, most students took the stance that reading was far superior to reading with an LLM. However, their arguments basically came down to comparing an article to its summary. In later experiments, we found quite positive results.

While these LLMs could not help a student access the same level of content they could access merely by reading, they could use their special ability of abstraction to serve as tools of what we might call distant reading (Moretti, 2013). Uploading one or more papers of a particular genre, students could then ask about generic features, such as typical sentence style or length, frequency of source citation in various sections of the paper, or even the diction of the paper. While LLMs are not specifically designed for genre analysis, they are, in effect, genre learning machines. As students move through writing activities, learning a new genre is often their first challenge. Whether or not the LLM could abstract out the conventions of the genre accurately, asking the students to use the LLM in this way helped focus their attention to the nature of genre.

Reading with LLMs can open up articles that were previously opaque to students, again, offering access to students of a wider range of reading skill levels and experience. Students have reported anecdotally to me to have used LLMs to explain articles to them in simpler terms. While such reading approaches should not replace reading the words, as my students argued in their papers, it may be a path into a text that would otherwise be beyond the comprehension level of the student. These tools can provide summary most easily of highly structured articles that follow strict conventions, such as APA-style research papers with clearly demarcated sections that include summary and separation of functions. Such papers, with their abstracts and keywords, are arguably already prepped for machine processing. For essays with more irregular structures, such as Turing's essay “Computer Machinery and Intelligence,” students could rely on machine summaries at a loss of nuance, unexpected turns, and minutiae that turn out not to be quite so minute.

Assignment: What AI Left Out

In the early days after the release of ChatGPT, November 30, 2022, a day that shall live in infamy, I was trying to find a way to revamp my assignments so they could not be easily completed by an LLM. Like most of my writing professor colleagues, our winter breaks had been full of yet-unseen levels of interest in the teaching of writing, specifically around the question: What are you going to do about ChatGPT? It seems that the world had all discovered LLMs at once, even if they had been around for years before.

While my colleagues suggested that their assignments were AI-proof, I was not so convinced. (Jeremy Douglass and I have expressed our skepticism in posting.) What if we let the students use LLMs or—perhaps more provocatively—invited them to use it? Their response: a volley of boos and tomato emojis. Reconsidering, I asked, what if students wrote responses to what the AI generated?

So, I issued a paper assignment, which I have seen peers also using, that begins by asking the LLM to produce a paper based on the assignment prompt for the class. Then, the paper they write is an evaluation of that paper, primarily based on what has been omitted from the paper. Conceivably, systems such as Claude and ChatPDF, that focus more on analyzing input texts, could write the response paper, so I leaned heavily into the students' lived experiences, their particular insights that an AI would not have access to. The assignment is a way to celebrate that unique offering each student brings to a topic.

While the first round of papers were focused a bit too much on critiquing the writing qua writing, a good portion of the students offered content drawn from their perspectives and experiences. I have since revised this assignment to ask students to focus primarily on particular observed details, lived experiences, and authentic insights, all valuable parts of any writing situation. As a result, the assignment moves away from a mere test of their ability to master generic college writing formats and instead makes them turn to identify what makes them unique: their identity and lived experience. The personal essay returns with a vengeance, although one must be careful about that genre, which can be so generic, too. LLMs have plenty of models of those.

The Breakdown Game: A Failed Experiment

Generative AI seemed an incomparable writing class tool. It offered everything from feedback on writing to assistance with reading and research. At least until we tried to use it as a guide through the entire writing process.

During the Future of Writing Symposium, Douglass offered a game that seemed perfectly suited to our goals. He called it the Breakdown Game. The basic exercise: In a popcorn or sequential participation exercise, have the students take turns listing a step in the writing process. Students can flesh out the process by dividing a step into more steps or adding an intervening step. For example, in between drafting an outline and writing a draft, a student could add giving feedback on the draft. This part of the exercise went quite well, actually, as students were able to spell out a writing process that was detailed and took into account much of the process that experienced writers take for granted. Also, as students began to run out of steps, they added opportunities for creating several versions of say a thesis statement and then choosing the best one, a process I recommend for most writing occasions. It was actually in the next step that we went awry, although perhaps awry in a way I should have expected.

By having students participate in a creative process with ChatGPT, as opposed to their peers or their instructor, I was relying on their ability to follow a path that was most productive. Furthermore, the speed at which the process was occurring did not leave time for reflection or reconsideration. If the three thesis statements were all bad, and a student did not recognize their weakness, all that followed (the outline, the fleshing out of the outline, the drafting) would be off track. But what was more problematic was that the essay that was produced at the end of this process was so foreign to the student, that they were too alienated from the prose to be able to revise it. The exercise amounted to asking a student to revise an essay someone else had written who, in the case of the students needing more assistance, had stronger fluency in conventional academic prose and whose writing seemed so finished even if it was ultimately empty.

That is a long way of saying that while the learning of the models may have been unsupervised, students deserve supervision, for LLMs inserted into the writing process have the potential to go wrong at every step in countless ways. So, while a trained writer versant in genres may have a ball taking ChatGPT out on the court for some street ball, new learners deserve, well, a coach.

That experience prompted me to develop a complement to the acronym for PROMPTS to name the process of responding to ChatGPT: EVALUATE

Explore the output. Read the generated content with an open mind.

Verify all facts because hallucination is real.

Analyze the internal logic because ChatGPT is stochastic not structured

Look up any references because they may not exist

Understand how the system works (and how that system leads to errors)

Ask it to revise what is faulty

Teach it to produce better

Enhance the text with your own writing

Those suggestions may not entirely protect a student who uses the system to generate an entire essay from scratch, but the acronym should provide a starting point for necessary conversations. But I fear my own essay has taken too serious a turn. Let us return to some play with a question: what’s a writing game that can invite critical reflection while stimulating some creative imagining?

Netprovs

One answer is netprov.

All these games and exercises with LLMs remind me that a good prompt, a few rules, and some guardrails can take writers of all skill levels far. Along those lines, my frequent collaborator Rob Wittig and I have developed three collaborative writing games on the topic of artificial intelligence, each with their own unique angle and context for play.

Netprovs are collaborative writing games that invite students and others to write together in response to prompts and a loose set of rules and guidelines. Wittig details these in his open access book. Netprovs are occasions for critical play, reflection, and “the voluntary healing of necessary relationships” (2022, p. 36). They are especially good at offering lighter responses to heavy anxieties.

Long before the release of ChatGPT and even Midjourney, we created a kind of summer school for artificial intelligence in The Machine Learning Breakfast Club. In this netprov, participants posted messages in an online teacher’s lounge for disgruntled educators tasked with helping recalcitrant AI.

Our second AI-inspired netprov was The Grand Exhibition of Prompts, which imagined a (not so) far-flung future where AI has taken over the creation of all art and where the celebrated human artists exhibit their beautiful prompts. Modeled after the grand salons of Paris at the Fin de Siècle, our Grand Exhibition offered a chance of a lifetime for aspiring prompt artists from one of three schools: Retro (for the ironically nostalgic), Emo (for the deeply expressive), and Fido (for the pet-inspired). While developing their prompts, participant artists told the story of their (fictional) artistic lives.

During that netprov, another was born. In one of the discussion channels on the Discord server where we held our netprov, someone noticed autocorrect off by itself smoking a cigarette and looking sullen. Apparently, these anthropomorphized AI had pretty rough lives themselves. They could use some counselors of their own. That tangent gave rise to Pr0c3ss1ng, the support group for AI assistants. Allow me to quote from the call:

We are the secret human helpers who give artificial intelligence programs the courage to face the day. We’re the ones who hear Siri's and Alexa's tearful doubts and try to guide them in their stormy and complex rivalry. We're the ones called on to help ChatGPT work through imposter syndrome. We're the ones tasked to console Google Search as it sees all its parent company's love going to the new Bard system. Not to mention the worries and resentments of legacy programs such as Autocorrect and Maps who feel eclipsed by the flashy newcomers.

Are we trained for this? No! Nobody is! We need support, too! That's why we've created a discussion group where we can share stories, seek tips, and put our heads together to understand the intermachinal dynamics of the AI boom. You're one of us! What do you see? What have you learned? Join us!

To participate, players posted fictional tales of angsty and upset AI to their fellow supporters and asked for advice on how to help the Alexas and Siris cope with the slings and arrows of serving humans in the modern age.

All three of these netprovs treat the subject of AI as an occasion to reflect more deeply on what makes us human. Whether in performing the struggle of helping others or the ineffable qualities of artistic creation, players put their humanity on center stage, while AI served as a kind of fun house mirror or, at other times, a foil for us and our fragile operating systems. To play with AI, and even the imagined exaggeration of the worlds AI will user in, gives students a way to transcend the hype while also working out their own responses in a non-judgmental context. They are invited to laugh at robots and humans alike and to delight in a truly human activity of laughing with others. In a netprov, all are welcomed into a safe environment of creative play.

Conclusion

AI can elicit quite a bit of fear, especially when it seems like it can perform our duties better than we can. I offer these activities as opportunities to do what humans still do best, to mess around, to test boundaries, not as service quality assurance testers but as unorthodox, unruly organisms who resist rules and rarely follow directions. To quote one of our players, when we presented him with the directions for our latest netprov, “Those are your rules.” He was determined to play by his own. Viva humanity.

While some courses are centered around tools and others centered around skills, I have had most success with courses centered around students. Looking back at the assignments that were most successful, I see exercises that invited students to play. Whether in netprovs or Turing Tests, students do not cease to surprise me.

For in the tool-centered course, we imagine these universal instruments that treat everyone the same. But as we unpack the white supremacist (heteronormative, etc.) training of ChatGPT and other LLMs, we see these machines for what they are, ways to whitewash the writing process, and just like standardized language enforcement, they tend to steam roll over students' individual voices. And as students incorporate more AI-generation in their writing process, they are in danger of silencing themselves, of taking themselves out of the equation.

Critical, creative, and playful uses of this technology with ready-made exercises that everyone can jump into offer ways for students to take on AI together and then to know it more fully, using those three words that are being systematically scrubbed from our universities: diversity, equity, and inclusion, words without which our language and culture become mere assembly lines for an unjust future with no humans empowered to critique it.

References

Bender, Emily M., et al. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? 🦜. Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (pp. 610–23). doi:10.1145/3442188.3445922.

Chiang, Ted. (2023, Feb. 9). ChatGPT is a blurry JPEG of the web. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/chatgpt-is-a-blurry-jpeg-of-the-web.

Eaton, Sarah Elaine. (2023). Six tenets of postplagiarism: Writing in the age of artificial intelligence. Learning, Teaching and Leadership. https://drsaraheaton.wordpress.com/2023/02/25/6-tenets-of-postplagiarism-writing-in-the-age-of-artificial-intelligence/.

Fan, Lai-Tze. (2023). Reverse engineering the gendered design of Amazon’s Alexa: Methods in testing closed-source code in grey and black box systems. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 17(2).

Kirschenbaum, Matthew. (2023, March 8). Prepare for the textpocalypse. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/03/ai-chatgpt-writing-language-models/673318/.

Marino, Mark C., and Rob Wittig. (2023). The grand exhibition of prompts. In Annette Vee, Tim Laquintano, and Carly Schnitzler (Eds.), TextGenEd: An introduction to teaching with text generation technologies. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/collections/textgened/creative-explorations/the-grand-exhibition-of-prompts/

Marino, Mark, and Chat GPT. (2023). Hallucinate this! An authoritized autobotography of ChatGPT.

McMurtrie, Beth, and Beckie Supiano. (2023, June 14). How professors scrambled to deal With ChatGPT. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/caught-off-guard-by-ai.

Mills, Anna, (Ed.). 2023. AI text generators: Sources to stimulate discussion among teachers. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1V1drRG1XlWTBrEwgGqd-cCySUB12JrcoamB5i16-Ezw/edit?usp=drive_web&ouid=116033055033861090565&usp=embed_facebook. Google Docs. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Moretti, Franco. (2013). Distant reading. Verso Books.

Raley, Rita, and Jennifer Rhee. (2023). Critical AI: A field in formation. American Literature, 95(2), 185–204. Silverchair, doi:10.1215/00029831-10575021.

Taylor, Patricia, and Mark Marino. (2024). On feedback from bots: Intelligence tests and teaching writing. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 7 (2), 110–117. doi:10.37074/jalt.2024.7.2.22.

Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433–60. doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433.

Turkle, Sherry. (1997). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of the Internet. New York: Touchstone.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. (1976). Computer power and human reason: From judgment to calculation. W. H. Freeman.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. (1966). ELIZA—A computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, 9(1), 36–45. doi:10.1145/365153.365168.

Wittig, Rob. (2021). Netprov: Networked improvised literature for the classroom and beyond. Amherst College Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.12387128

Yin, Ziqi, Hao Wang, Kaito Horio, Daisuke Kawahara, and Satoshi Sekine. (2024). Should we respect LLMs? A cross-lingual study on the influence of prompt politeness on LLM performance. arXiv.org, https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.14531v2.