Mind the Gaps: Evaluating Student Perceptions on GenAI and the Future of Writing

Jeanne Law Kennesaw State University

James Blakely The Ohio State University

John C. Havard Kennesaw State University

Laura Palmer Kennesaw State University

Introduction

Academic responses to the emergence of generative artificial intelligence have followed a perhaps predictable pattern, similar to previous technologies that disrupted writing instruction, such as the word processor and world wide web. Tech evangelists such as Bill Gates cautioned that concerns about artificial intelligence have historical precedent and that although the technology would require adaptation, those challenges could be navigated (Gates). However, early academic responses tended to be more histrionic in nature. For instance, in the widely circulated Chronicle article “Will Artificial Intelligence Kill College Writing?”, Jeff Schatten succinctly summarized the early fears provoked by the technology by asking, “If anyone can produce a high-quality essay using an AI system, then what’s the point of spending four years (and often a lot of money) getting a degree?”

Due to these fears, early discussions often hinged on the dangers of a decline in student writing due to student usage of artificial intelligence. The Association for Writing Across the Curriculum, for instance, was compelled to stress the dangers to learning posed by student reliance on artificial intelligence, stating that “As scholars in the discipline of writing studies more fully explore the practical and ethical implications of AI language generators in classroom and other settings, we underscore this: Writing to learn is an intellectual activity that is crucial to the cognitive and social development of learners and writers. This vital activity cannot be replaced by AI language generators.” As such, much early discussion hinged on policing student AI use through the development of AI detectors and other means. However, while detectors may be useful as a starting point for identifying inappropriate AI usage, they have also thus far been revealed to be unreliable and to produce false positives (Nelson), and moreover to be biased against non-native English speakers (Liang et al). Therefore, it may be impossible to police artificial intelligence entirely at this time, and in any event it is pedagogically problematic to focus on surveilling, disciplining, and punishing students as a pedagogical response to their use of a new technology that will be widely used in non-educational sectors.

With this growing realization, scholars have turned to discussing more nuanced models for asking students to engage with artificial intelligence. This shift is reflected in the statements of the MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI. For instance, in a correspondence statement on National Priorities for Artificial Intelligence, the Task Force represent a number of concerns regarding AI, calling for an AI Bill of Rights ensuring citizens and consumers are apprised when writing is AI-sourced; consideration of linguistic diversity in the regulation of AI that ensures AI does not further diminish endangered languages; and transparency around the corpuses used to train large-language models. However, they also acknowledge writing instruction as a critical site for ensuring that students are educated on such issues. For instance, they stress that given the potential challenges posed to democracy by the proliferation of AI-generated content, writing instructors have a responsibility to teach students how AI writing works and how to recognize it. Given this, they call for support for teachers at all levels as we adapt our teaching methods and materials. If we want to prepare an educated citizenry to interact critically with AI-generated content, the United States must provide resources to educators. However, we think it essential to recognize that given the scale of the time and resource commitment required of teachers and institutions, existing educational institutions and funding streams are not adequate to support the rapid development of curricula for critical AI literacy to supplement existing digital literacy curricula.

Similarly in their first published working paper, while the Joint Task Force affirms “that higher education’s specific institutional role of credentialing the achievements of students as individuals means that generative AI cannot simply be used in colleges and universities as it might be in other organizations for efficiency or other purposes” (2), they also stress that the technology “has the promise to democratize writing, allowing almost anyone, regardless of educational background, socioeconomic advantages, and specialized skills, to participate in a wide range of discourse communities. These technologies, for example, provide potential benefits to student writers who are disabled, who speak languages other than English, who are first-generation college students unfamiliar with the conventions of academic writing, or who struggle with anxiety about beginning a writing project. They also augment the drafting and revising processes of writers for a variety of purposes” (8). They similarly point out a number of pedagogical usages, such as applications in the writing process and classroom applications such as using the technology as a proxy for dictionaries (9-10).

Further evidence of this trend may be found in the introduction to the WAC Clearinghouse’s TextGenED repository of AI assignments, in which Tim Lanquintano, Annette Vee, and Carly Schnitzler explain the different paradigms composition instructors use to approach AI in their classes: “prohibition,” “leaning in,” and “critical exploration.” They explain that “We are skeptical [prohibition] will be a viable model,” and moreover that “complete prohibition might very well lead to an eventual de-skilling of students.” At the same time, they argue that “leaning in” is “an uncritical stance that accepts the discourse of inevitability” and “is unlikely to empower students or educators.” However, they present a third model, “critical exploration,” in which instructors teach student the ethics of using AI, AI literacy regarding how the technology works, and develop strategic assignments meant to help students understand those issues while also ensuring the integrity of writing instruction in those courses. The TextGenEd collection provides a uniquely comprehensive repository of assignments pertaining to “rhetorical engagements,” “AI literacy,” “ethical considerations,” “creative explorations,” and “professional writing.” They ultimately appeal that “As Big Tech rushes ahead in its AI arms race with the intention of having large language models (LLMs) mediate most of our written communication, writers and teachers are forced to consider issues of prompt engineering, alignment, data bias, and even such technical details as language model temperature alongside issues of style, tone, genre and audience.” The growing presence of such repositories suggests the progress with which writing teachers have begun to accommodate AI in their teaching practices.

While the authors of this paper concur with Lanquintano, Vee, and Schnitzler that it is important for faculty to think about how to engage students with AI, we find that in the foregoing scholarly discourse there has been limited systematic attention paid to the experiences of students. Yet students bring with them preconceptions and assumptions about AI that will inevitably impact their reception and engagement with AI assignments. The present study intervenes in this discussion by providing data regarding student perceptions of AI at a large state R2 institution and discussion of the pedagogical implications of those findings.

Methodology

Our large-scale study was approved as IRB FY23-559 by Kennesaw State University; the research team includes faculty, graduate students, and administrators from KSU's Department of English as well as faculty and administrators from the Department of Technical Communication and Interactive Design (TCID). We are at the beginning of what we hope to be a longitudinal study of students’ attitudes toward generative AI use in writing contexts. We have experienced strong interest across multiple disciplines at KSU, and we plan to categorize research findings along several trajectories. For this particular study, we focused primarily on first-year students enrolled in ENGL 1101 and ENGL 1102. We also performed a snapshot method in a smaller population of students enrolled in a non-General Education Technical Communication course (TCOM 2010). While this snapshot is preliminary in terms of comparison to our target population, we did find interesting trends that we present in our article.

Using the Qualtrics XM survey platform with Text and Stats IQ analysis tools, our team designed an eight-question instrument with both closed and open-ended response options. Our goal was to begin a preliminary measurement of first-year students’ attitudes toward generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI) in their writing writ large, with specific attention paid to gen-AI in their academic lives. We were most interested in their responses towards AI as the future of writing and whether or not they considered gen-AI cheating in their academic writing courses.

Study and Respondent Demographics

Our team surveyed students enrolled in first-year writing courses at Kennesaw State University (KSU) in Fall semester 2023. Kennesaw State University is a public, R2 doctoral-granting school founded in 1963. It comprises two campuses totaling 544 acres. The acceptance rate is 68%. KSU is the second largest university in Georgia, with a total enrollment of 43,268. Of this number, 39,005 are undergraduates.

In Fall 2023, KSU welcomed more than 8,500 students as first-year students, who were enrolled in more than 350 first-year composition (FYC) courses taught by almost 100 faculty. These students were demographically diverse in several ways:

- 38% self-identify as first-generation students

- Approximately 50/50 gender split

- 25% self-identify as Black or African American

- 13% self-identify as Hispanic of Latinx

- 6% self-identify as Asian

- 5% self-identify as two or more races

- 48% self-identify as White

- 79% of undergraduates are full-time students

KSU students are mostly conventional college-age, with 84% of undergraduate students falling between the ages of 19–24. KSU has a robust dual-enrollment program, with more than 800 students.

Survey Validity and Reliability

Our mixed methods survey on first-year students' attitudes toward AI use in writing courses is a reliable and valid instrument for measuring initial attitudes towards generative AI. We designed the survey as a short snapshot that would balance the content validity of collected data with students’ taking the time to complete the survey. To this end, we used a 3-point Likert-like scale of yes/no/sometimes in our closed questions, with follow-ups to these questions that were open-ended, asking students to explain their answers in more detail. Our survey sample as of October 15, 2023, was 942 respondents, which represents 11% of first-year enrollment. We continue to make this survey available through a systematic distribution that entails the Department Chair (John) and the Director of First-Year Composition (Jeanne) sending the survey link to all instructors in the First-Year Composition (FYC) Program encouraging them to send the link to their students via email, LMS post, or classroom time. We also send email reminders during the semester and promote the survey at monthly Department and FYC meetings. Although we recognize that this distribution method may not reach all students, we are confident that the diversity in rank and employment status of instructors in FYC gives us the necessary respondent population.

The survey items are consistently measuring the same construct (attitudes towards generative AI in writing), and the survey results are consistent across 930 responses. Additionally, the survey items adequately cover the range of content that is relevant to the construct of interest, and they correlate well with other measures of the same construct. We used Qualtrics Text and Stats IQ analysis along with Excel data analysis and visualization. We further plugged our data into the Claude and Bard generative AI large language models (LLMs) to triangulate data. While the generative AI models gave us accurate overall impressions, Qualtrics and Excel analysis provided the deep dives necessary to draw conclusions. Two researchers on our team (James and Jeanne) ran the data sets and agreed on the results of each.

The study context is replicable across many institutions of higher learning. KSU first-year students represent a diversity that can be scaled and generalized to many other doctoral-granting public institutions in the United States. The survey questions can be added to and contextualized to specific institutions while still maintaining the overall construct of measuring student attitudes. Our research team acknowledges, though, that this survey is a temporally constrained measurement that shows student attitudes towards gen-AI in a specific moment in time (Fall semester 2023 for the data presented in this chapter). Given the exponential growth of AI and its endless means of integration into all aspects of our students’ writing lives, we will need to continue to distribute the survey each semester to determine how student responses change over time.

The reliability and validity of this survey make it a valuable tool for researchers who want to study students' attitudes toward AI use in writing courses. Versions of this survey can be used to track changes in students' attitudes over time, to compare the attitudes of distinct groups of students, and to identify factors that influence students' attitudes.

Our survey results demonstrated internal consistency with regard to reliability. For example, students answered similarly on two questions that we designed to consistently measure the same attitude/construct. Our results indicate that the survey items are consistently measuring the construct of attitudes toward AI use in writing courses, and that the survey results are consistent within a semester in the fall of 2023, with mass knowledge of gen-AI being just a year old.

Comparison with Students in Introduction to Technical Writing

In our goal toward learning more about student attitudes toward AI use in writing courses, we wondered if there would be any notable differences between the students enrolled in FYC and our introductory course in technical writing, TCOM 2010. The Department of Technical Communication and Interactive Design (TCID) is a standalone department. It is not housed within English or under the umbrella of “writing studies.” TCID is the home of a BS in Technical Communication; it is this degree program that delivers the service class, TCOM 2010: Technical Writing, to students.

Kennesaw State University is home to the colleges of Engineering and Computer Science/Software Engineering as well as the schools of Architecture and Construction Management. While Architecture does not require a technical writing class, Engineering, Computer Science/Software Engineering, and Construction Management include TCOM 2010 in their required curricula. In some cases, this inclusion serves to meet the requirements of an accrediting body (i.e., ABET); in other cases, the inclusion of TCOM 2010 serves to provide students with the necessary communication competencies for a STEM workplace.

We surmised that our population of primarily STEM students could provide responses that differ from the general FYC population. STEM students may view a new technological advance, such as a tool that assists with writing, as very valuable. Additionally, their STEM mindset could reveal dimensions in attitudes that may not appear in the FYC population. As the survey was based on gathering data on student attitudes about gen-AI, we determined we had an invaluable opportunity for comparison.

While FYC students represent the overall university population well, TCOM 2010 classes are primarily taken by students in Computer Science, Industrial Systems Engineering, Software Engineering, Construction Management, and Information Technology. TCOM 2010 classes consist, on average, of 65% male and 35% female students; the content of the course centers on the genres of technical communication in addition to audience analysis, and document presentation.

Using the same survey developed to assess the attitudes of FYC students, the Chair (Laura) and the Technical Communication Program Coordinator reached out to faculty teaching TCOM 2010 and, following the lead of FYC, encouraged them to send the link to their students via email, LMS post, or classroom time. As of October 15, 2023, we received 81 responses from the 712 students enrolled in TCOM 2010. This matches the 11% response rate from the FYC student population. The analytical methods for FYC responses were applied to the TCOM 2010 data set.

As we describe and explain preliminary results, we understand the shifting nature of our topic as well as the fluidity of conversations surrounding artificial intelligence. We address our findings within a “moment in time,” the specific temporal space in which we are writing up the results as we have them (in this case, 2023 data). We do this with a deep understanding that, at the moment we write our research study, there are still responses to the surveys coming in and there are still thousands of conversations yet to be had.

Discussion

As scholars and teachers in writing studies, members of our research team have witnessed the deluge of generative artificial intelligence tools that have swarmed mass culture since November 2022. Our students have witnessed and participated in this infusion as well. In the following section, we discuss preliminary findings, including initial passes at comparisons between populations of first-year writers who took the survey and undergraduate students enrolled in a 2000-level technical communication course, which is required for engineering and computer science majors at Kennesaw State University. This second population, which had 81 responses as of October 2023, consists of undergraduate students enrolled in TCOM 2010, an introductory technical writing course. TCOM 2010 is not currently part of the core curriculum, but functions as a service-learning course for Computer Science and Engineering.

Quantitative Analysis Discussion on First-Year Writers

When asked if they have heard of GPT or similar AI programs, student respondents reported overwhelmingly that they had (90%). This high number was expected, given the ubiquitous nature of “all things AI” in mass media and on social media platforms.

The data from our survey question three is of particular interest when we think of how first-year students may use generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI) in different rhetorical situations for writing. Table 1 shows the results as of October 10, 2023. When broken down into five distinct categories, the data appears overwhelming in terms of use in academic writing. For example, 73% of respondents indicated that they never use gen-AI in their academic work. When we collapse the different categories of answers that report usage in varying degrees, however, we show that 28% do use gen-AI in some rhetorical situations of academic writing. While this data is preliminary and overarching, we believe that these percentages indicate consistency with answers to other parts of Q3, with 30% of students reporting that they use GPT and similar gen-AI in their personal writing (overall) but 70% never do. The variations on the Likert-esque scale are important, but, based on our interactions with students and our discussions with instructors, we believe the most significant numbers come from the actual reporting of use overall. For us, given the discussions of gen-AI around our university in most disciplines, we can assert that even a “sometimes” response may be all a student is willing to give, even as an anonymous answer. We have found in speaking to first-year students in our own courses and program, that they are reluctant to admit to gen-AI usage for fear of being labeled cheaters or “lesser-than” in their writing abilities. Our anecdotal observations match what we believe are consistent survey measures of the attitudinal construct.

| Q3: I have used GPT or similar AI programs... | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| in my professional/work writing | in my academic writing | in my personal writing | |

| Never | 78.5% | 72.6% | 69.7% |

| Sometimes | 14.1% | 21.8% | 21.4% |

| About half the time | 2.0% | 1.7% | 1.5% |

| Most of the time | 3.9% | 2.8% | 4.4% |

| Always | 1.5% | 1.1% | 1.9% |

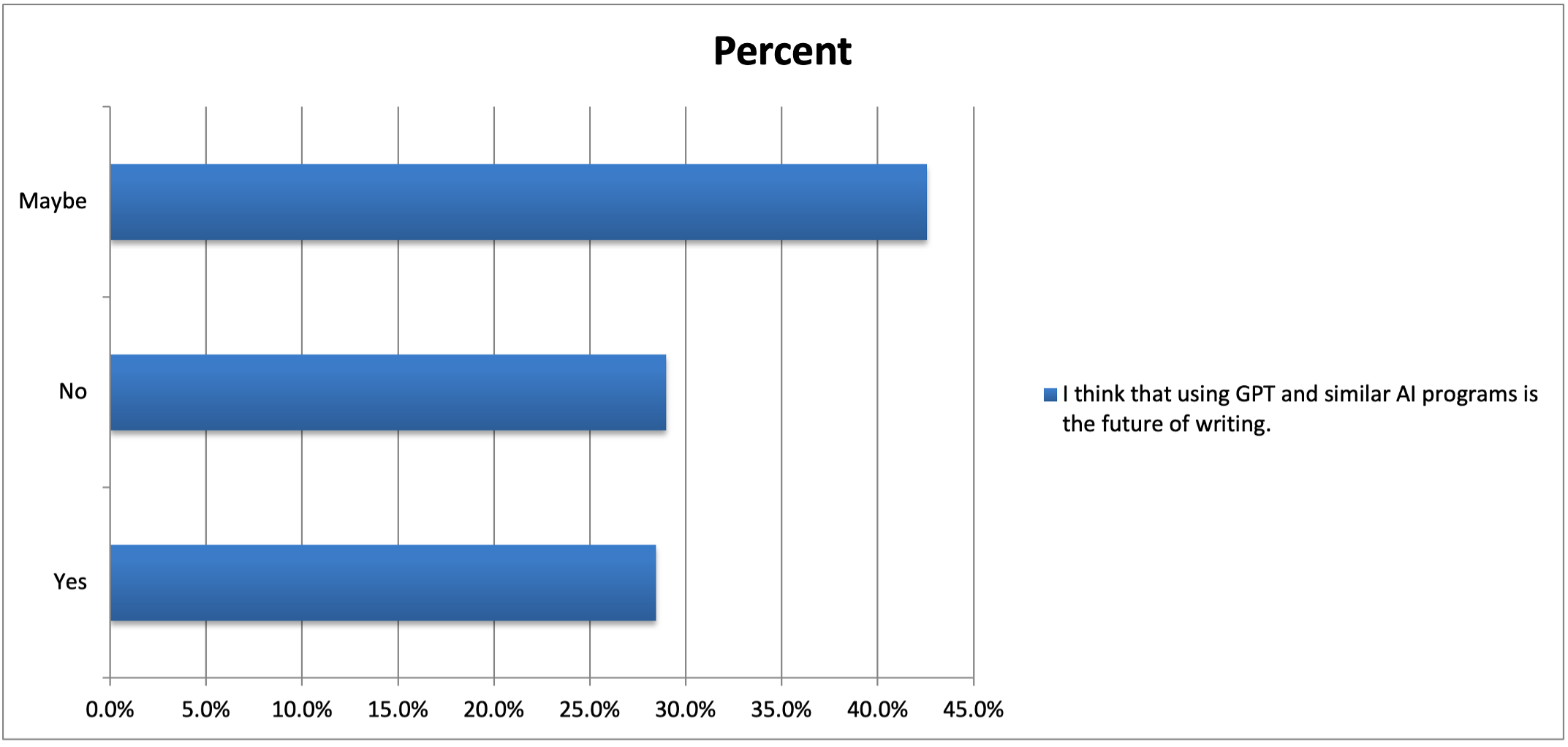

Students showed interesting splits when asked if generative artificial intelligence is the future of writing. In answers to this particular question, students were almost evenly split in terms of agreement and disagreement. Figure 2 shows that 28% of students believed that gen-AI is the future of writing, while 29% did not. Again, the majority of students fell in the middle, with 43% answering maybe. Figure 2 shows consistency in responses related to other survey questions.

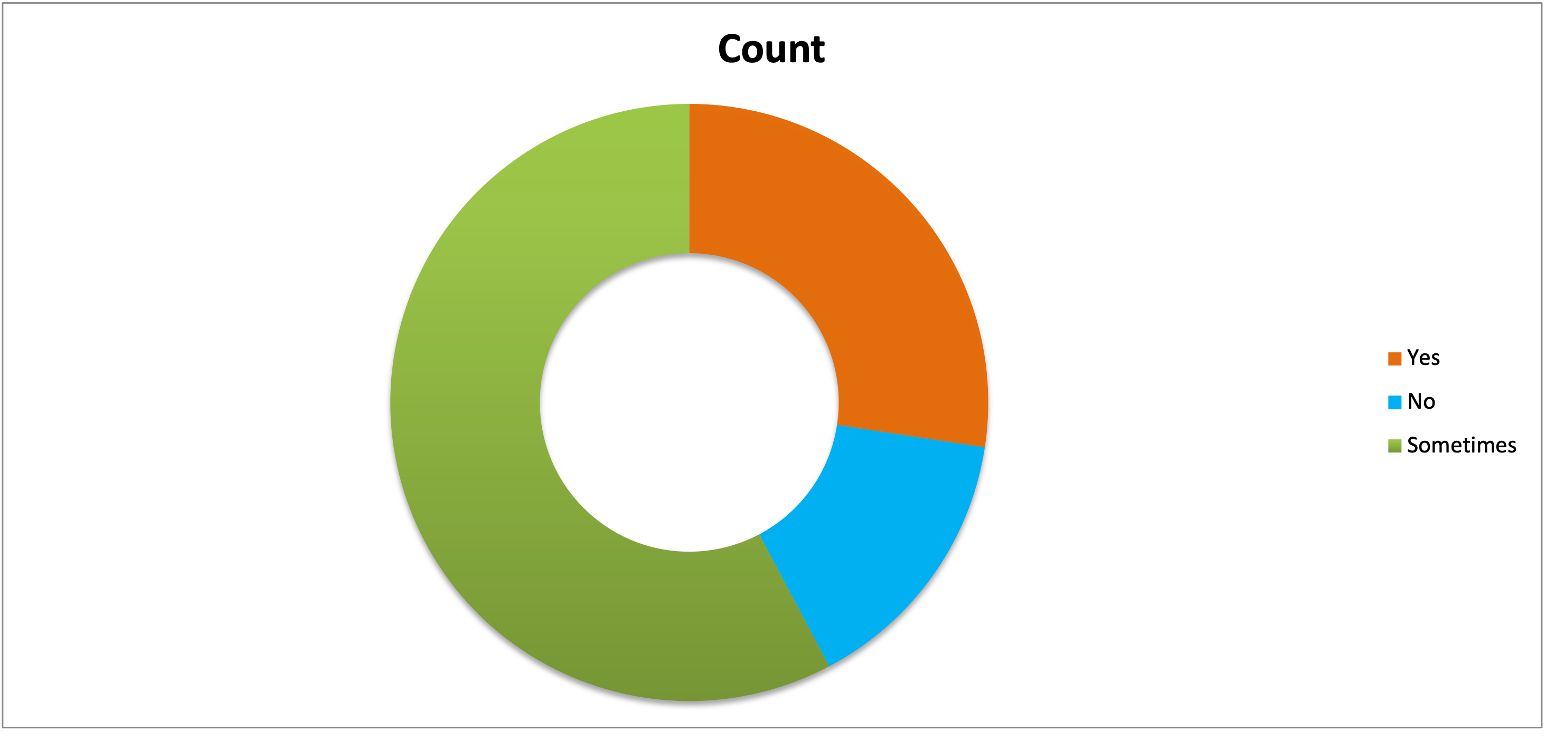

Students seemed equally split when we asked if they considered gen-AI use in academic spaces to be cheating. Again, the data shows that students fall somewhere in the middle of what they are willing to answer regarding this hot-button topic. While 27% answered "definitely yes, gen-AI use is cheating," 15% reported such use is "definitely not cheating." Overwhelmingly, most students were in the middle ground, with 58% reporting sometimes. The doughnut visualization in Figure 3 shows the “sometimes” responses in green, the “yes” responses in red, and the “no” responses in blue. In terms of generalizing this data, we faced a conundrum. We had no way of knowing what that large percentage of “sometimes” meant to students.

Here is where a mixed methods approach is most valuable when measuring attitudes. As a follow-up to the answers to this question, we asked students to describe why they answered the way they did. We used Qualtrics Text IQ to perform a sentiment analysis of qualitative responses to this question, using keywords to filter student responses and aligning them to the answers to the previous closed question.

Qualitative Analysis Discussion on First-Year Writers

To measure students' responses to quantitative questions that had qualitative attitudinal follow-ups, we used Qualtrics Text IQ and dual-rater review to obtain what we believe are accurate and valid sentiments based on keyword analyses. We present several unique findings that help instructors and administrators take a deeper dive to understand what students have on their minds.

Interestingly, when we filtered responses to the question asking students to explain their answer to “AI use is cheating,” the word plagiarism showed up in 25 responses, or 3% of total respondents. While at first pass, this number seems not significant, we argue it is significant for a few reasons:

- We did not use the word plagiarism in the survey at all. Three percent of students equated cheating and plagiarism as synonyms.

- Of this three percent, 20% of students who used the word plagiarism agreed that "AI use is cheating."

- Of the students who answered that "AI use is not cheating," (15%), they also reported in their explanations that “there is nothing wrong with it” at a rate of 80%. More than 13% of these same students who answered that AI-use is not cheating reported that AI-use resembled tutoring or writing center visits.

In general, students reported the following phrases (or similar) the most:

- “It’s my words that I put into the bot”

- “It’s unfair for students to use it to get a better grade”

- “We will use it in our work lives so we need to be prepared for it”

- “It’s OK to use it to brainstorm and create but not to copy from”

As we dig deeper into the data (and as the data set continues to grow), we want to focus on the two questions tied to cheating and perform a deeper sentiment analysis to help us understand these findings.

Another initial finding that intrigued us came in the general feedback question about academic writing. When we filtered results for the word “academic,” the word only showed up in general responses 2% of the time. Of that 2%, 78% of the references to the word “academic” were coded as negative sentiment. Example phrases associated with “academic” seemed to indicate that students placed themselves where we have heard some professors anecdotally place them: as not understanding when and how to use generative artificial intelligence (gen-AI) in academic writing.

As researchers studying generative AI, we would be remiss to not utilize these very tools in our own data-dive. For this purpose, we utilized Claude, an LLM chatbot built by Anthropic, a startup founded by former members of ChatGPT’s parent company, OpenAI. Claude’s robust feedback system and training algorithm, built on a variety of texts including books, articles, and conversations, enables it to understand nuances and relationships in language that we found other LLMs unable to replicate. For this reason, we found Claude to be the most accurate AI assistant for the tasks we assigned. (Note: this was the case in 2023; in 2024 and 2025, Jeanne has found that GPT 4o and o3 give her better benchmarking for multiple types of qualitative and quantitative analysis, including sentiment analyses and trends marking.)

To effectively demonstrate Claude's ability to analyze data across sets, we carefully crafted prompts to guide our engagements toward useful output. Our primary strategy involved breaking down our analysis goals into discrete, intermediate steps, improving Claude’s reasoning and response quality, as well as using clear, intentional language and providing relevant contexts. Through these techniques, we obtained the following results in data review and analysis.

Prompt #1 focused on extrapolating specifics of quantitative data from both our first-year composition and technical communication data sets:

- “I'm going to provide you data from a survey of nearly 1,000 first-year college students focusing on opinions about/experiences with AI. Can you synthesize this data? Thank you.”

- “I'm going to provide you data from a survey of undergraduate students enrolled in a 2000-level technical communication course focusing on opinions about/experiences with AI. Can you synthesize this data? Thank you.”

Prompt #2 focused on sourcing and contextualizing significant open-ended responses in relation to this quantitative data:

- “Can you offer up some particularly important open-response answers from the document I provided?”

Prompt #3 focused on testing Claude's ability to handle more than one text at a time.

- “Now I would like you to provide an expansive cross-analysis of these data sets against one another. Please refer to the first set as the 'Composition' set and the second as the 'TCOM' set.

Claude's analysis was consistent with our own findings across all three prompts. With prompt #1, it identified the same key themes we observed—students acknowledging benefits like efficiency, idea generation, and grammar improvement alongside risks like plagiarism and diminished critical thinking. For prompt #2, Claude effectively sourced and framed relevant student insights, reiterating the same trend we see of students valuing AI for assistance but avoiding full reliance for a myriad of reasons. To demonstrate Claude’s capabilities more clearly, we have included its full response to prompt #3 below:

“Absolutely, here is a more detailed cross-analysis between the TCOM student survey data and the Composition student survey data on perspectives about AI in writing:

Usage of AI Writing Tools

- The TCOM survey had higher reported usage of AI writing tools like GPT, with 77% saying they had used them compared to 57% of Composition students.

- In open responses, TCOM students provided more examples of using AI tools in academic contexts (writing papers, getting clarification on assignments) and professional contexts (improving resumes/cover letters, writing work emails).

- Composition students more often reported using AI tools for personal writing and creative pursuits in open responses. Very few mentioned using it for schoolwork.

- This suggests TCOM students may be more comfortable integrating AI tools into their academic and professional writing compared to Composition students. It aligns with TCOM's focus on technical communication for the workplace.

Views on Ethics of AI Writing Tools

- Students across both surveys expressed mixed views on whether AI tool use constitutes cheating.

- In open responses, TCOM students provided more examples of using AI tools in academic contexts (writing papers, getting clarification on assignments) and professional contexts (improving resumes/cover letters, writing work emails).

- The most common perspective was that it depends on how the tools are used. Using AI to generate ideas, improve flow, check grammar, etc. was seen as acceptable, while using it to write full assignments was widely seen as cheating.

- However, a segment of TCOM students (26%) felt AI was not cheating compared to only 9% of Composition students. This ties back to the first point about TCOM students being more open to AI integration in writing.

- Concerns about plagiarism, lack of originality, and undermining the learning process emerged clearly in both datasets. Students value critical thinking skills involved in writing that AI does not provide.

AI Writing Tools' Role in the Future

- TCOM students were more optimistic about AI playing a major role in the future of writing. 60% said it "maybe" would be the future compared to 43% of Composition students.

- Composition students more strongly rejected the idea of AI replacing human creativity and jobs. Many emphasized the importance of emotion, soul, and humanity in writing that AI lacks.

- Still, sizeable segments in both surveys (32% TCOM, 43% Composition) were uncertain if AI would dominate writing. This suggests students have mixed views on if AI capabilities will advance enough to surpass human skills.”

Here, Claude again lays out findings consistent with our interpretation of both data sets, revealing interesting contrasts in attitude between first-year composition and technical communication students.

Collectively, this exercise demonstrates Claude’s ability to accurately assess qualitative data. By engaging in effective prompt engineering, our research team was able to utilize LLM capabilities to produce results consistent with our own research and analysis across more than one data set. We were able to conduct limited cross-analytical work, Claude offering inventory and insight of more than 1,000 responses. More generally, this exercise also highlights gen-AI’s potential usefulness in research processes: surfacing key themes, establishing relevant connections, and transforming data into actionable insights.

Comparison of TCOM 2010 and FYC Students: AI Usage and Perceptions

| Category | TCOM (%) | First-Year Writing (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Used AI for Academic Writing | 87 | 65 |

| Used AI for Personal Writing | 80 | 50 |

| Used AI for Professional Writing | 72 | 30 |

| Believe AI Use is Always Cheating | 20 | 30 |

| Believe AI Use is Sometimes Cheating | 60 | 50 |

| Believe AI Use is Never Cheating | 20 | 20 |

| Think AI is the Future of Writing | 50 | 51 |

| Think AI is Maybe the Future of Writing | 30 | 31 |

| Think AI is Not the Future of Writing | 20 | 18 |

AI Usage in Writing

Table 2 demonstrates three differences in student attitudes when comparing TCOM 2010 students and first-year composition students. For example, students were asked how often they use AI in different writing contexts. The trends show variability in AI usage for academic work, personal writing, and professional writing, with notable differences between the two groups:

- Academic Writing: Both groups use AI occasionally for schoolwork, but TCOM students do so at a slightly higher rate. Many use AI as a writing tutor or idea generator for essays and reports. For example, they might ask an AI to suggest how to organize a report or to rephrase a sentence. First-Year Writing students also experiment with AI for homework (like getting feedback on a draft or finding synonyms), but a larger portion of first-year writing students say they “rarely or never” use AI for assignments compared to TCOM students. This indicates that while AI is present in academic work for both, Technical Communication majors have more fully embraced it as part of their writing process.

- Personal Writing: Usage of AI for personal tasks (such as journaling, social media posts, or creative writing for fun) is relatively low in both groups. Only a few students in each group report regularly using AI for personal writing. Those who do might use it for things like drafting emails, writing resumes, or casual creative brainstorming. Generally, TCOM students reported slightly more personal AI use—perhaps utilizing tools to polish personal projects or communications. First-year students seem to use AI personally mostly out of curiosity (for instance, asking ChatGPT fun questions or help with a personal statement) rather than as a routine practice.

- Professional Writing: Here we see one of the biggest differences. Technical Communication students are far more likely to use AI for professional or work-related writing. Many TCOM respondents have either internship experiences, part-time jobs, or class projects mimicking workplace writing (like proposals, technical manuals, or business emails). They reported using AI tools to generate outlines, edit professional documents, or simplify complex technical jargon. In contrast, First-Year Writing students rarely use AI in a professional context, largely because most are new college students without professional writing duties yet. Any mention of professional use by first-year students was minimal (for example, maybe using AI to help write a cover letter for a summer job). Essentially, AI as a writing assistant in the workplace is already being explored by TCOM students, while first-year students have little exposure to that context.

- Need for Clarity: Both groups expressed that they’d like clear guidelines from instructors or institutions about AI usage. The ambiguity about what counts as cheating leads to anxiety. For example, students want to know: Is using Grammarly or an AI tutor allowed on assignments? Should they cite AI if it gave them an idea? This shared concern highlights that while students are open to using AI, they are also keenly aware of integrity and want to avoid unintentional misconduct.

Comparative Qualitative Data from TCOM 2010 and FYC Students

TCOM students highlighted genAI as a useful editorial and brainstorming tool but noted risks of losing creativity. Similarly, FYC students appreciated AI for organizing ideas but criticized it for making writing robotic and less personal.

AI in Academic Writing

TCOM students viewed genAI as a double-edged sword: a tool for learning but also a risk to foundational skills in writing. FYC students echoed this sentiment, stressing the need for guided use to prevent dependency and ensure effective learning outcomes. Sample quotes that represent data trends include:

TCOM: 'AI enhances learning when used for concept understanding, much like a calculator helped with math.'

TCOM: 'Using ChatGPT can constitute cheating if it replaces drafting and skill-building, but not if used as a tool for learning.'

FYC: 'AI democratizes access to learning resources, but improper use risks dependency and undermines academic integrity.'

FYC: 'Teachers should guide AI usage to prevent misuse while helping students learn to use it as a resource.'

AI Usage in Professional Writing

Both groups valued genAI for improving professional communication. TCOM students noted its utility in resume building and formal email writing, while FYC students warned against over-reliance, emphasizing the need for human oversight to maintain professionalism. Sample quotes that represent data trends include:

TCOM: 'I use AI to draft professional emails and improve resumes, which makes writing faster and more effective.'

TCOM: 'AI lacks the nuance needed for critical tasks, but it’s helpful for formatting and grammar improvement.'

FYC: 'AI helps polish professional documents, but there’s a risk of over-reliance on its outputs.'

FYC: 'Using AI for workplace writing can save time, but human oversight is essential to maintain quality.'

Our initial comparison between TCOM 2010 and FYC students reveals nuanced perspectives on the use of generative AI in academic and professional contexts. Both groups share a recognition of genAI's potential to enhance writing efficiency, assist in brainstorming, and serve as a resource for professional communication. However, they express consistent concerns about over-reliance on genAI, the erosion of originality, and ethical implications in higher education settings. TCOM students appear slightly more inclined to view genAI as a collaborative tool, emphasizing its role in enhancing existing work. In contrast, FYC students stress the importance of preserving originality and learning outcomes, often framing genAI as a double-edged sword that requires careful guidance. This analysis highlights the shared understanding of genAI's transformative potential while emphasizing the need for structured, ethical integration of these tools to balance innovation with skill-building and academic integrity.

This research represents only preliminary results; we plan further analysis of responses based on evolving sets of questions each academic year. We collected data each semester up to Fall 2024 and have collaborated with colleagues in our Colleges of Engineering and Business to survey their students as well. Further, Jeanne developed a prompting method based on student attitudes and articulated needs. For current publications on further data usage, readers may check the endnotes of this article. We conducted this research under Kennesaw State University's IRB#: FY23-559.

Implications

As we continue to write, research, and analyze findings, we believe our initial research snapshots provide a clear exigence for the continued study of students’ attitudes towards how and why they deploy generative AI tools in their writing in academic, professional, and personal spaces. We plan to present preliminary findings as well as longitudinal results as we seek to understand these attitudes and plan pedagogical strategies to meet our students where they are in the Zeitgeist of genAI.

The implications of discussions around genAI are clear: our students know about it, they talk about it, and they use it, in increasing numbers and modalities. As we continue to build on our knowledge, we also recognize that conversations involving generative AI also involve listening to colleagues' experiences and acknowledging affordances and constraints upon us and our students. We welcome feedback, collaborators, and deeper conversations into both our study and pedagogical strategies as we adapt and flex in response to what generative artificial intelligence will mean in the coming semesters and the coming years in our field. As generative AI specifically continues to reshape writing practices, these insights serve as a reminder that our pedagogical approaches must adapt accordingly. By meeting students where they are and providing guidance on how to critically and ethically engage with genAI, we can ensure that genAI becomes a tool for enhanced learning rather than academic shortcuts.

References

Association for Writing Across the Curriculum Executive Committee. (2023). Statement on artificial intelligence writing tools in writing across the curriculum settings. https://wacassociation.org/statement-on-ai-writing-tools-in-wac/

Gates, Bill. (2023, July 11). The risks of AI are real but manageable. GatesNotes. https://www.gatesnotes.com/The-risks-of-AI-are-real-but-manageable

Liang, Weixin, Yuksekgonul, Mert, Mao, Yinig, Wu, Eric, & Zou, James. (2023). GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers. Patterns, 4, 1–4.

MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI. (2023). Working paper: Overview of the issues, statement of principles, and recommendations. Modern Language Association of America and Conference on College Composition and Communication.

MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI. (2023). Re: FR Doc. 2023-11346, National priorities for artificial intelligence. Correspondence.

Nelson, Jason. (2023, July 24). OpenAI quietly shuts down its AI detection tool. Decrypt. https://decrypt.co/149826/openai-quietly-shutters-its-ai-detection-tool

Schatten, Jeff. (2022, September 14). Will artificial intelligence kill college writing? Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/will-artificial-intelligence-kill-college-writing

Vee, Annette, Laquintano, Tim, & Schnitzler, Carly. (Eds.). (2023). TextGenEd: An introduction to teaching with text generation technologies. WAC Clearinghouse. https://wac.colostate.edu/repository/collections/textgened/