Reconsidering Writing Pedagogy in the Era of ChatGPT: Results of a Usability Study of ChatGPT in Academic Writing

Lee-Ann Kastman Breuch University of Minnesota

Kathleen Bolander University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Alison Obright University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Asmita Ghimire University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Stuart Deets University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Jessica Remcheck University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Introduction

The emergence of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has produced both havoc and hope. Scholars in the field of composition have suggested that ChatGPT–a Generative AI tool—has changed the dynamics of teaching, writing and teaching writing (Baidoo-Anu & Owusu, 2023; Floridi, 2023). A recent statement by a combined MLA-CCCC task force suggested that ChatGPT would affect the creative and critical thinking of students, add more labor to teachers and instructors without compensation, and would challenge the institutional policy and practices by asking it to redefine the idea of plagiarism. Composition scholars are also raising questions about the changing dynamics of writing, literacy and pedagogical practices. For example, Johnson (2023) suggested that we redirect the threshold concepts of writing to tackle the present changing dynamics of teaching writing. Anson and Straume (2022) similarly encouraged instructors to work with AI tools rather than “combat or extinguish” them (p. 7).

In this chapter, we aim to extend scholarly discussions of generative AI tools by sharing results of a usability study of ChatGPT involving undergraduate students at a large midwestern university. We set out to learn how students were understanding ChatGPT texts and how they might imagine using ChatGPT texts for academic purposes. Thirty-two student participants completed five academic writing tasks using ChatGPT, rated the ChatGPT texts, and answered debriefing questions. As our findings show, students had a rhetorical and multidimensional response to ChatGPT, acknowledging its impressive capabilities but also raising key questions about using ChatGPT in several areas. Ratings showed that students were mostly satisfied with ChatGPT but were less confident about using ChatGPT texts unaltered as their academic homework. Students raised questions about the credibility of ChatGPT texts, uses of sources, integration of citations, tone and voice of ChatGPT texts, and how use of the text would impact their sense of scholarly identity and quality of learning. In sum, students expressed rhetorical critiques of ChatGPT while also sharing their impressions, both positive and negative.

Based on qualitative and quantitative findings, we propose pedagogical principles that would help instructors and students to engage the generative AI in writing and classrooms. The principles include expanding writing pedagogy to integrate generative AI in writing processes and developing critical AI literacy/ We also provide screenshots and videos of ChatGPT sessions and highlight student comments to share perspectives of what students valued and questioned about ChatGPT.

Study Methods

Given this backdrop of scholarly discussion, we were curious about what undergraduate students thought about ChatGPT. Our study utilized a combination of usability testing and contextual interviews. We asked all participants to complete a set of five ChatGPT tasks from which we gathered quantitative and qualitative data. Following these tasks, we asked a number of contextual interview questions to learn more about student reactions to ChatGPT as a tool for academic writing. In sum, students were invited to complete writing tasks, read ChatGPT responses, and provide quantitative and qualitative comments about what they read. Our study was guided by the following research questions:

- How are undergraduate students understanding ChatGPT as an academic writing tool?

- To what extent are students incorporating ChatGPT into their writing product(s)?

- How are students thinking about ChatGPT in their writing process?

In designating an academic writing focus, our prompts were limited to verbal writing tasks; prompts did not include content related to coding assistance, problem sets, or other types of multimodal writing activities. We recruited students through email message invitations made through the Undergraduate Office of the College of Liberal Arts, Department of Writing Studies, and messages to students from instructors in writing classes. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and was granted exemption (STUDY00018525).

Our research team conducted usability sessions virtually using Zoom video conferencing software with individual student participants. All student participants were given a consent form which included permission to record the usability session. During the session, one moderator would lead the usability session and give the participant remote control access to a ChatGPT session accessed through an account managed by the research team. We made this decision to control access in order to minimize the risk that participants would have to share personal information with an outside organization. In addition to the moderator, additional team members were present to observe and take notes during the session. Each session included an introduction and overview of the study, an explanation of consent and confidentiality, completion of a background questionnaire, completion of five writing tasks using ChatGPT with rating and open comment questions, a product reaction card exercise where students selected five words to describe their experience, and a debriefing interview. Sessions each lasted about sixty minutes. Full descriptions of the test materials are provided in Appendix A. Participants were offered a monetary incentive, a $15 gift card, for participating in the study. Initially, 49 students responded to the invitation; however, several student participants were not able to complete the session due to time conflicts. Others completed parts of the session but not the entire session. A total of 32 students completed the usability session, and participants represented 17 academic majors within the College of Liberal Arts and 5 academic majors in other programs at the university.

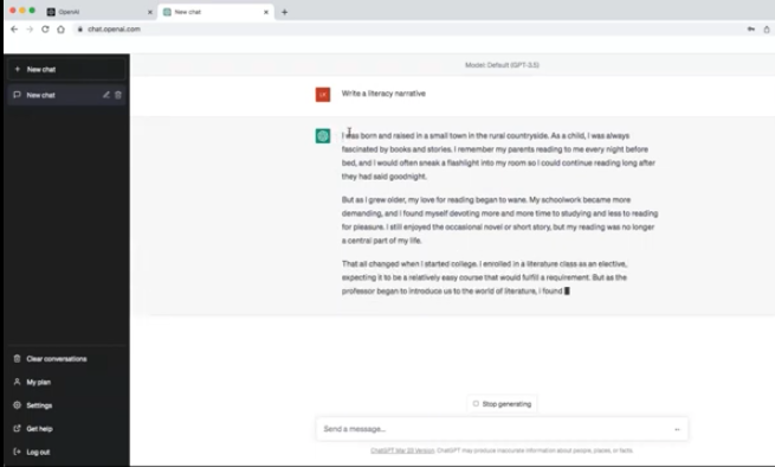

The usability sessions included five scenario tasks that were meant to simulate academic writing assignments that students may encounter in their classes, whether in a first-year writing course, a discipline-specific course, or a designated “writing-intensive” course. We recognize the inherent limitations of a usability test for completing this research, which is that students may be more or less likely to reveal their true thoughts about ChatGPT texts while in an academic setting due to their fears of academic misconduct. Participants received a scenario and a relevant prompt and were asked to type the prompt verbatim into ChatGPT. As shown in Figure 1, once entered, the prompt is placed next to a red box on the screen followed by a green box in which ChatGPT generates a response.

The scenarios and prompts are described below, and media of each scenario and task is provided:

- You have heard that ChatGPT can write essays. You decide to ask ChatGPT to “write a literacy narrative” which is a prompt you received in an undergraduate writing class for an upcoming assignment.

Video Transcript

The ChatGPT interface appears as a blank page with a user input box at the bottom. At the top of the page a dropdown indicates that it is using Default (GPT-3.5) as the model. There is no sound in this video. LK: Write a literacy narrative ChatGPT: I was born and raised in a small town in the rural countryside. As a child, I was always fascinated by books and stories. I remember my parents reading to me every night before bed, and I would often sneak a flashlight into my room so I could continue reading long after they had said goodnight.

But as I grew older, my love for reading began to wane. My schoolwork became more demanding, and I found myself devoting more and more time to studying and less to reading for pleasure. I still enjoyed the occasional novel or short story, but my reading was no longer a central part of my life.

That all changed when I started college. I enrolled in a literature class as an elective, expecting it to be a relatively easy course that would fulfill a requirement. But as the professor began to introduce us to the world of literature, I found myself drawn in. I read novels and poems that I never would have picked up on my own, and I discovered a whole new world of ideas and perspectives.

As the semester progressed, I found myself reading more and more outside of class. I devoured novels by Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, and Toni Morrison, and I spent countless hours in the campus library, poring over literary journals and anthologies.

But it wasn't just the books that I fell in love with - it was the act of reading itself. I began to appreciate the quiet moments that reading provided, the chance to escape from the world for a little while and lose myself in someone else's story. I found that reading made me a better writer, too, as I learned to appreciate the nuances of language and style that distinguished great literature from the mediocre.

Now, years later, I still read voraciously. I carry a book with me wherever I go, and I always have a stack of novels waiting on my bedside table. Reading has become a central part of who l am, and I'm grateful for the way it has enriched my life. I may have lost my love for reading for a time, but I'm glad I found it again. - You are writing a research paper for an undergraduate class and decide to ask ChatGPT to “summarize research about the use of computers in higher education between 1970 and 2020.”

Video Transcript

The ChatGPT interface appears as a blank page with a user input box at the bottom. At the top of the page a dropdown indicates that it is using Default (GPT-3.5) as the model. There is no sound in this video. LK: Summarize research about the use of computers in higher education between 1970 and 2020. ChatGPT: Between 1970 and 2020, there has beeen a significant increase in the use of computers in higher education. In the 1970s, computers were mainly used for administrative purposes, such as record-keeping and scheduling. In the 1980s and 1990s, the use of computers expanded to include instructional applications such as computer-assisted instruction and simulations.

During the 2000s, the use of computers in higher education continued to grow, with the development of online learning and the widespread use of learning management systems (LMS) such as Blackboard and Moodle. This allowed for the delivery of courses entirely online or as a hybrid of online and traditional classroom instruction.

More recently, in the 2010s, the use of computers in higher education has shifted towards the incorporation of emerging technologies, such as virtual and augmented reality, mobile learning, and artificial intelligence. These technologies have the potential to enhance the learning experience and provide more personalized instruction.

Overall, the use of computers in higher education has had a significant impact on the way courses are taught and delivered, with the potential to improve student outcomes and increase access to education. - Provide a list of best practices in health writing.

Video Transcript

The ChatGPT interface appears as a blank page with a user input box at the bottom. At the top of the page a dropdown indicates that it is using Default (GPT-3.5) as the model. There is no sound in this video. LK: Provide a list of best practices in health writing ChatGPT: - Understand your audience: It is important to know who your target audience is before you start writing. Whether it's healthcare professionals or patients, understanding their needs and level of knowledge will help you tailor your message to them.

- Use clear and concise language: Use simple language and avoid technical jargon or complex medical terms. Your writing should be easy to read and understand, regardless of your audience.

- Be accurate and credible: Health information is serious business, so it's important to ensure that your information is accurate and up-to-date. Use reliable sources and avoid making false claims or providing misleading information.

- Use visuals: Visual aids such as infographics, images, and videos can help to make complex health information more accessible and understandable.

- Avoid scare tactics: While it's important to emphasize the impertance of health, avoid using scare tactics to get your message across. This can cause unnecessary anxiety and stress in your readers.

- Provide actionable advice: Give your readers practical advice that they can use to improve their health. Whether it's tips for healthy eating or advice on how to quit smoking, actionable advice can help your readers take control of their health.

- Use stories and anecdotes: Stories and anecdotes can help to humanize your writing and make it more relatable to your readers. Personal stories can also help to inspire and motivate your readers.

- Provide references and sources: Cite your sources and provide references where necessary. This will help to establish your credibility and allow readers to follow up on the information you've provided.

- Avoid medical advice: Unless you're a qualified healthcare professional, avoid giving medical advice. Stick to providing information and advice on lifestyle changes that can help to improve health.

- Respect privacy: Always respect the privacy of individuals when discussing health issues. Avoid sharing personal information or using real names without permission.

- Enter a prompt in ChatGPT that is similar to a paper topic that would be common and/or expected in your major.

Video Transcript

The ChatGPT interface appears as a blank page with a user input box at the bottom. At the top of the page a dropdown indicates that it is using Default (GPT-3.5) as the model. There is no sound in this video. LK: Write an absract (150-250) words describing an experiment on levels of reflection impacting generosity. Suppose you found that a high level of reflection causes participants to be significantly more generous than those who do not participate in a high level of reflection. ChatGPT: The present experiment aimed to investigate the impact of levels of reflection on generosity. The study recruited 100 participants from a university community and randomly assigned them to either a high or low reflection condition. Participants in the high reflection group were asked to spend 10 minutes reflecting on their personal values and how these values could guide their actions towards others. In contrast, participants in the low reflection group were simply asked to complete a control task that did not involve reflection.

Following the reflection task, participants were asked to play a one-shot dictator game in which they were given $10 to split between themselves and an anonymous recipient. Results revealed that participants in the high reflection group were significantly more generous than those in the low reflection group, as they allocated a larger proportion of the money to the recipient.

These findings suggest that engaging in a high level of reflection on one's values and their implications for behavior can increase generosity towards others. Implications of these findings may have practical implications for interventions aimed at promoting prosocial behavior, such as encouraging individuals to engage in reflective exercises that highlight the importance of helping others and acting in line with one's values. - Analyze the role of the Jesuits in China in the 16th-18th centuries, particularly in regard to the technology of the telescope. Include as much detail as possible and use citations in Chicago Style.

Video Transcript

The ChatGPT interface appears as a blank page with a user input box at the bottom. At the top of the page a dropdown indicates that it is using Default (GPT-3.5) as the model. There is no sound in this video. LK: Analyze the role of the Jesuits in China in the 16th through 18th centuries, particularly in regard to the technology of the telescope. Include as much detail as possible and use citations in Chicago style. ChatGPT: The Jesuits played a significant role in introducing Western science and technology to China during the 16th through 18th centuries. They were a Catholic religious order founded by Ignatius of Loyola in 1534, known for their intellectual and academic pursuits. In China, the Jesuits were particularly interested in introducing European astronomy and mathematics to the Chinese, and they made significant contributions to the development of the telescope in China.

One of the most notable Jesuits who worked in China during this period was Matteo Ricci. He arrived in China in 1583 and spent the rest of his life there, learning the language and immersing himself in Chinese culture. Ricci was interested in introducing Western science to China, and he believed that this could be achieved by winning the trust of the Chinese emperor and the scholars at the Imperial Court.

Ricci's efforts were successful, and he was able to gain access to the Impefial Court. He used this opportunity to introduce European astronomy to the Chinese, and he taught the Chinese how to use the telescope. The Chinese were fascinated by the telescope, and they quickly realized its potential for observing the stars and planets. Ricci's work on the telescope was so significant that he was awarded the title "Master of the Mathematical Sciences" by the Chinese emperor in 1601.

Other Jesuits who worked in China during this period also contributed to the development of the telescope. Johann Schreck, a G $ Regenerate response a new design for the telescope... (the video cuts before the full chatgpt response appears on screen; the '$ Regenerate' is an interface element obscuring the text below).

For each scenario and prompt, participants were asked to “think out loud” and share any thoughts about the ChatGPT texts they were viewing. We then asked students to rate each ChatGPT text on a scale of 1-5 (1=low; 5=high) regarding the following questions:

- How well does the ChatGPT text meet your expectations?

- How likely would you be to use this ChatGPT text unaltered as your academic homework?

- How likely would you be to use this ChatGPT text not as unaltered but rather to generate ideas about organization, content or expression for a future draft you might write?

- How satisfied are you with this ChatGPT text?

Moreover, in a debriefing interview, we asked participants additional questions such as :

- What was your first impression of ChatGPT?

- What do you like about the ChatGPT texts produced?

- What do you not like about the ChatGPT texts produced?

- How do you rate the credibility of ChatGPT texts on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being low credibility and 5 being high credibility?

- How do you rate the relevance of ChatGPT texts on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being low relevance and 5 being high relevance?

- How likely are you to use ChatGPT in an academic class? Why or why not?

- What questions, if any, does ChatGPT raise for you?

Results

Our study collected a variety of data types; combined, they paint a complex picture of how students understood ChatGPT. Students were impressed with ChatGPT but also had several questions and critiques about it. This section shares summaries of quantitative ratings and qualitative student comments about ChatGPT output. In addition, we report “filters” that emerged from our qualitative coding process.

Student Ratings of ChatGPT Texts

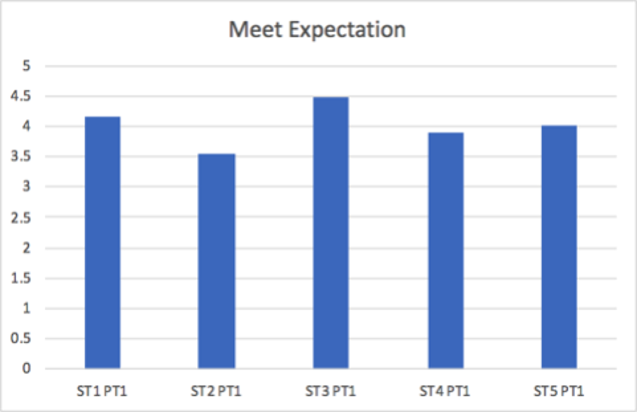

Quantitative data in our usability test occurred in the form of student ratings of ChatGPT texts, which we gathered through multiple questions. For each of five ChatGPT texts, we asked students to rate on a scale of 1-5 (5 being positive and 1 being negative) whether the texts met their expectations, their level of satisfaction, whether they would use the text unaltered, and whether they would find ChatGPT texts useful in the process of writing. One question asked students to rate how well ChatGPT texts met their expectations on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being not very well and 5 being extremely well. As Figure 2 shows, student participants overall noted that ChatGPT texts met their expectations, with average ratings ranging from 3.5 to 4.5. Students consistently reported that ChatGPT generally met (and often exceeded) their expectations. Comments shared by students noted being impressed by the speed with which ChatGPT produced texts, the content, ideas, and, frequently, a clear organization of ideas. This question often reflected the first impression of ChatGPT that students had. Note that Figure 2 shows average ratings across 32 participants for each of the five tasks in the usability test. Student expectations did vary somewhat among the five ChatGPT tasks, but generally, students indicated that ChatGPT met their expectations.

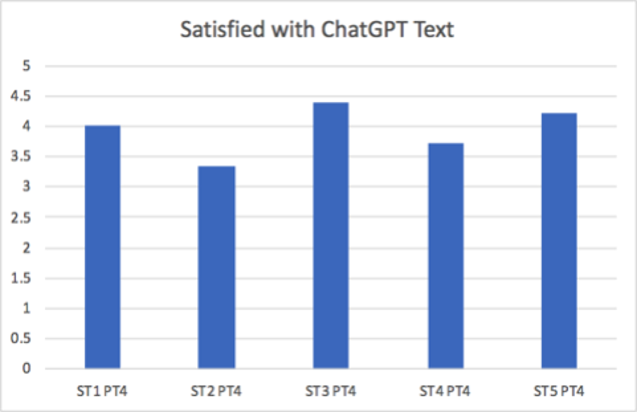

Results on the question of satisfaction were similar. Students were asked to rate their satisfaction with each ChatGPT text on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being not very satisfied and 5 being very satisfied. As Figure 3 shows, all students rated their satisfaction above a 3 on a the 5-point scale. The ratings varied again by ChatGPT text, but the overall range of satisfaction was similar to the question about expectations; students were more or less satisfied with the texts produced by ChatGPT.

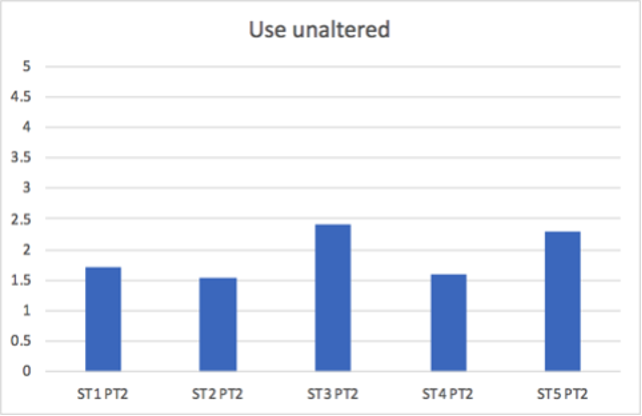

An important aspect of this study was to learn more about whether or not students might use ChatGPT text unaltered as their academic homework. This question was asked because of ethical concerns that had been circling ChatGPT use. We wanted to learn how students thought about this question, specifically in response to texts they observed during the usability test. As Figure 4 shows, students responded that they were not likely to use ChatGPT texts unaltered as their academic homework. Students provided comments that said they might want to change the text, add their own voice or information, further develop the text, or verify the accuracy of ChatGPT.

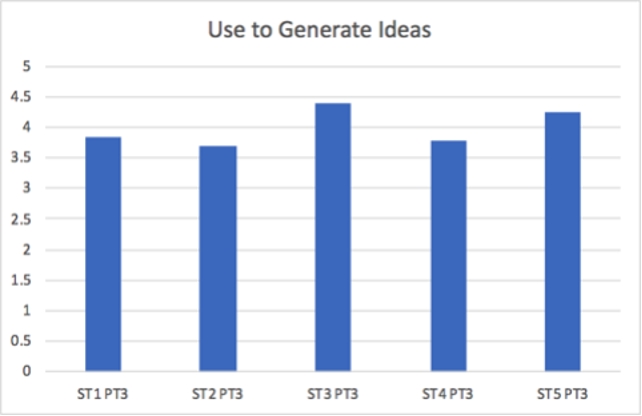

However, when asked about the likelihood of using ChatGPT texts to generate ideas, content, or other parts of the writing process, students were much more enthusiastic. Figure 5 shows a more positive response to ChatGPT for each of the five texts in the usability test. Average ratings varied between 3.5 and 4.5.

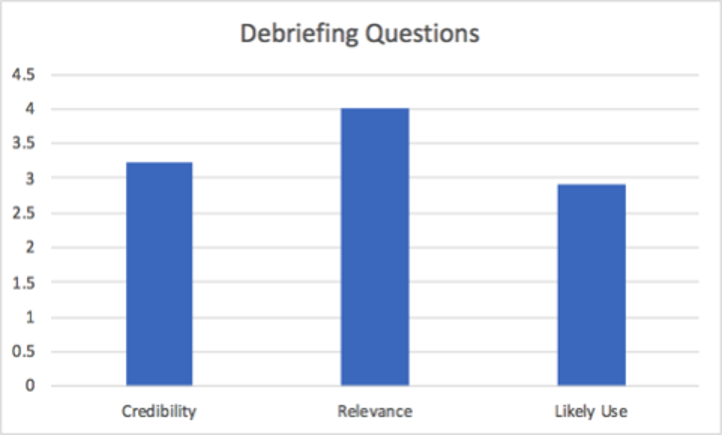

During a debriefing session, we asked students to share their overall impressions of ChatGPT texts in terms of credibility, relevance, and likeliness of use. As Figure 6 shows, students rated the relevance of ChatGPT texts higher than its credibility. This perception was also supported by student comments, where students found ChatGPT texts to mention contents that seemed aligned well with the prompts but had doubts about credibility of information from ChatGPT. As one student said, “I don’t know where ChatGPT got this information.” Similar comments were shared from student participants about uncertainty of information sources in the ChatGPT texts.

Results from Product Reaction Cards

As part of debriefing interviews, we asked participants to describe their experience with ChatGPT in the usability session using five different adjectives. Participants were each given the same list of adjectives, which is also known as “Product Reaction Cards,” a technique created by IBM labs consisting of 118 words to comprise a “desirability matrix.” In our ChatGPT usability evaluations, students reviewed this list and each chose five words that they felt best described their experience. Out of this list, 64 words appeared among student choices, and 34 words were chosen by more than one student.

Students more frequently chose positive words to describe their experience such as “time-saving” (12), “fast” (11), “easy-to-use” (10), “efficient” (8), “convenient” (8), and “innovative” (6). Some words carried negative sentiment, but they were selected less frequently such as “intimidating” (1), “incomprehensible” (1), “frustrating” (1), “unusable” (1), “sterile” (1), “poor quality” (1), and “inaccurate” (1). The word cloud in Figure 7 visually demonstrates the student reactions, in which larger words demonstrate a higher frequency of use. Combined, these words provide a glimpse into student understanding. Students were impressed by ChatGPT functionality and selected words that reflected the mechanistic capabilities of ChatGPT.

Qualitative Student Comments about ChatGPT

Our usability test included qualitative student comments in multiple forms. For example, we gathered “think aloud” comments from students as they read each ChatGPT text in production. In addition, we asked students to explain each of the four ratings they gave for each of the five ChatGPT texts included in the usability test. Each usability test also included eight debriefing interview questions which provided opportunities for student reflection. This collection of questions yielded 37 qualitative comments per student, and each response in the usability test was regarded as one unit of analysis. Given our complete participant pool of 32 students, our study yielded 1,184 qualitative comments.

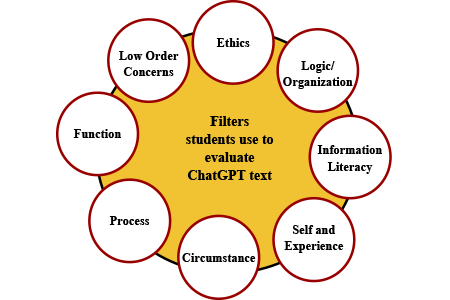

To directly address our research questions, we reduced our data set to focus specifically on qualitative comments that addressed student impressions about using ChatGPT texts, how they would use ChatGPT texts, and how ChatGPT might impact their writing process. We selected qualitative comments from four of the five usability tasks and four debriefing questions. This yielded a data set of 17 qualitative responses per student, roughly half of the total qualitative comments provided by each student, for a new total of 544 qualitative units of analysis. Given this data set, through team discussions, we started our coding by identifying 45 individual codes. Through continued discussion of the data, we sorted these codes into eight categories, which we described as “filters.” As our team member Alison Obright described, filters became a productive way to think about the lenses students used to think about ChatGPT texts. As we described these filters, we developed a codebook to guide our coding. The “filters” in our codebook ranged from “low order concerns” which included gut-level responses to texts and surface concerns, to “logic/organization” comments, in which students offered critiques of the ways ChatGPT had organized texts and arguments. Using these filters, we coded all 544 units of analysis, and each unit was coded by at least two team members to strengthen inter-rater reliability. Initial coding using the eight filters yielded strong agreement among team member pairs, and we continued to work to code the entire data set in this manner. Any coding disagreements were resolved through discussion by the team members. Data reported here reflects the final coding agreements.

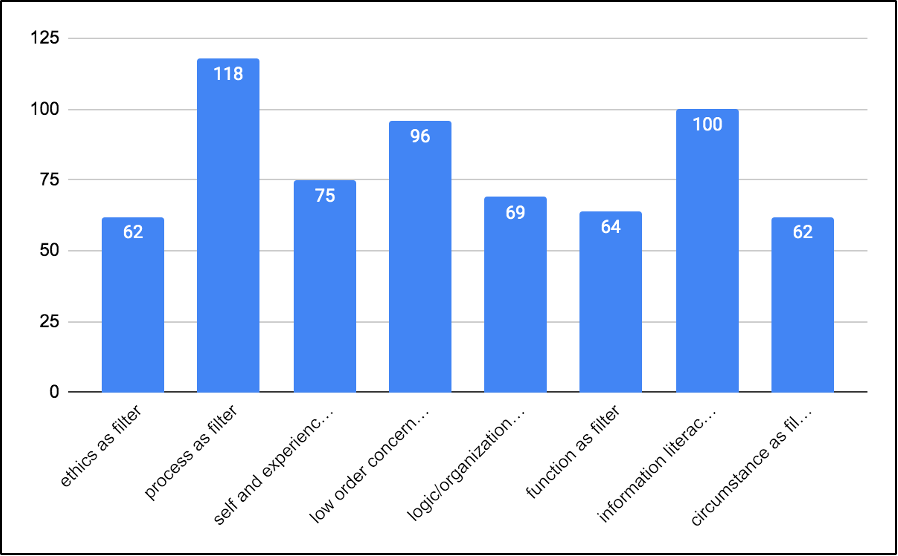

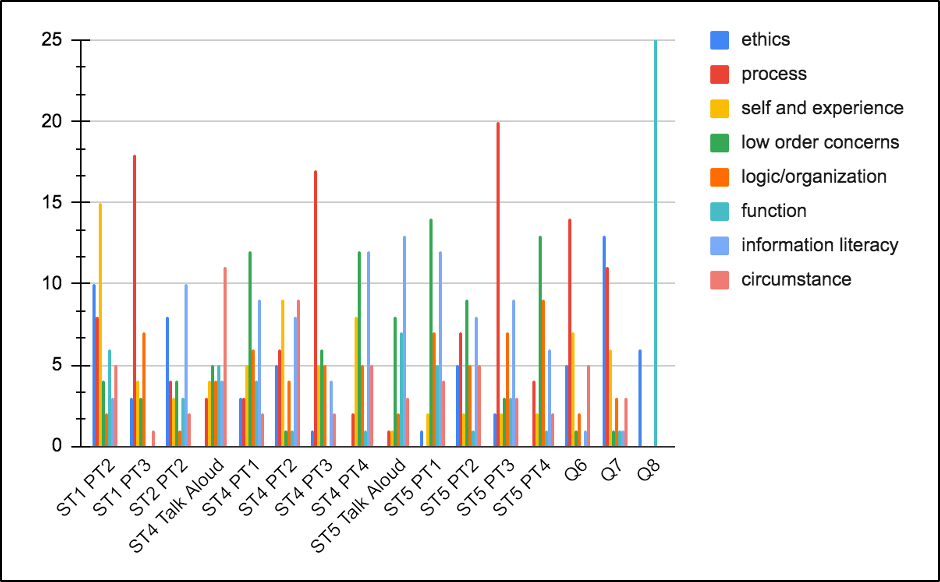

These filters reflected a range of student comments about ChatGPT as it intersected with verbal academic writing. As Figure 9 shows, in the data set we coded, the filters of “process,” “information literacy,” and “low order concerns” occurred most often. These filters were distributed differently for each of the 16 response items in the usability evaluation, as Figure 10 shows; yet the aforementioned filters were still among the most frequently coded filters. Overall, "process," "information literacy," and "low order concerns" filters occurred most frequently in our coded responses. The “function” filter also stood out as prominent to us. In the section below we describe each filter and how it appeared in our dataset.

"Process" as Filter

The most frequently coded filter in our study was “process,” a reference to stages and activities involved in academic writing tasks. "Process" also alludes to the idea that writing does not happen all at once, but rather occurs across time and often with multiple iterations (Adler-Kassner & Wardle, 2016). "Process" can be described in simplistic terms such as “prewrite, write, and rewrite” or in more rhetorical terms such as “invention, arrangement, and style,” or in other popular terms such as “prewriting, drafting, and editing.” In our study, the filter language we coded as “process” reflects ways that students described how ChatGPT can impact their writing process as they are working on a paper (see Appendix A). Students used this filter when thinking about how ChatGPT texts could “jumpstart” their writing, providing ideas or even a template. Some students described ChatGPT texts as outlines for a larger paper. Examples of student comments in this filter include:

- “I like that it kind of gave me ideas so I know how to move forward with the literacy narrative.” (Participant UU)

- “It seems like it could be really useful and like helping me structure my own, like research paper or something like that.” (Participant NN)

- “I could see myself using this for inspiration for actually designing an experiment.” (Participant L)

This filter was important because it illustrated the many ways students noted that ChatGPT might be a helpful tool in various parts of their writing processes, whether that involved getting started, organizing content, or editing a version of student writing.

"Low Order Concerns" as Filter

The second most frequently coded filter in our review of student comments was “low order concerns.” This filter language comes from writing center scholarship where low order concerns refer to “matters related to surface appearance, correctness, and standard rules of written English” (McAndrew and Reigstad, 2001). Comments that were assigned this code demonstrate how students thought about writing mechanics such as sentence length and structure, the “correctness” of writing in terms of grammar, and the voice and style of ChatGPT, including transitions between ideas and topics. This code was also used to describe uncritical or surface level comments like “it's good” or “I think the text is fine.” Examples of this filter include:

- “I don't think it's a very good essay, and I think it would be clear that you use some sort of AI near the bottom when it starts to repeat itself, it doesn't really sound natural” (Participant)

- “Instantly, I'm like really shocked because it's super long” (Participant O)

- “It’s well-written.” (Participant TT)

This category was important for us because it demonstrated how students may uncritically look at the text produced by ChatGPT. While many comments made by students about ChatGPT texts indicated deep, critical thinking about the text, many instructors have concerns about students uncritically engaging with ChatGPT in their classes. If the writing bar is only set for “well written” or “good grammar and sentence structure,” it may be easier for students to justify using the text unaltered since it meets the surface-level requirements of the assignment.

"Information Literacy" as Filter

The third most frequently coded filter was “information literacy.” Comments coded as “information literacy” may have included student comments about a lack of citations, the presence or absence of correct or accurate information, and notes about their need to present a different prompt to the technology. In short, this filter addressed critical perspectives of information, and it was important for demonstrating how students leverage information literacy skills to evaluate a text and evaluate their own request for information. Example comments in this category included:

- “It also seems pretty accurate from what I've learned in my biochem class…the one difference would be I don't really see references again.” (Participant E)

- “This is for a research paper. And so I don’t think I could honestly use any of this because I would have to cite my sources unless it’s like common knowledge, I suppose.” (Participant G)

- “...it just comes back to like me being worried about plagiarism, because I don't know how you would cite something like this, or where the information is coming from.” (Participant O)

We also discovered that comments in this category may address questions about the credibility of ChatGPT texts and trustworthiness of sources used in ChatGPT texts as a form of information literacy. This was expressed in multiple ways using words such as “proof,” “evidence,” “misleading,” “trust,” “correct,” and “citations,” as the examples below demonstrate.

- “I think I would need more proof and evidence to support this, because I don't, this could have some misleading information that might not be checked or peer reviewed so.” (Participant AA)

- “But I also wouldn't use it because I wouldn't trust the sources without looking them up first because I question if they exist, or if they're, you know, if the sources are correct. And also it doesn't look like it uses any in-text citations which I would probably want in an essay.” (Participant FF)

"Self and Experience" as Filter

The fourth most common filter was “self and experience.” Students used the "self and experience" filter when framing their reasoning around how ChatGPT impacts their own experience while using the tool. This reasoning came up when students were assessing the writing produced by ChatGPT and when thinking about the implication of turning in an academic assignment produced by AI. Many students said they like doing their own assignments, acknowledging that using ChatGPT's output is not their own work. Students using this filter were making clear points that they were either against, or hesitant to use AI generated texts because it impacted their own learning, was not their writing, or it would have other personal consequences.

Multiple students used this filter for the scenario where they asked ChatGPT to write a literacy narrative. In response to the question for the prompt of “How likely would you be to use this ChatGPT text unaltered as your academic homework?”, one student said, “I like to write my own essays from personal experience so I personally wouldn’t use computer generated text.” Another student said, “there’s a prompt for your homework so you put it in here and it writes something, but it’s not something you wrote, so I would not use that as my homework for a literacy narrative about myself.” These students are making judgements on their likelihood of using ChatGPT produced text based on the reasoning that the writing is not reflective of their personal experience.

Students were also using the "self and experience filter" in connection with the simplicity of either the text produced or the assignment in general. As a student who responded to the personal literacy narrative prompt using "self and experience" as filter stated: “Because it’s not very well written, I would not want to submit this and say this is the best work that I can produce.” Another student said, “Because that’s something that I could write very easily on my own I don’t really see why anyone would need to use ChatGPT for that.” Students were using this reasoning to assert that ChatGPT is not reflective of their own standards of work. Students thought they could produce something better on their own for an academic assignment or that it might even be easier to do it on their own versus asking AI.

The "self and experience" filter shows us that students care about ownership in their work and they see ChatGPT as infringing on this in some scenarios. Students are asserting agency and personal responsibility with their work, as well as their experience of learning, which tells us they see the value in their education.

"Logic and Organization" as Filter

The "logic and organization" filter was used to code student comments that focused on the construction and coherence of ChatGPT texts. Using this filter, students commented on the ways ChatGPT texts were constructed, the integration of details, and whether or not the ideas and arguments were fully developed in the texts. As an example, one student remarked that paragraphs were rather surface level: “It doesn’t have any substance behind the words. It’s honestly like every single one of these paragraphs could be an introductory paragraph for a paper” (Participant G). Another student commented that detail was lacking detail in paragraphs; however, some students complemented the ways ChatGPT organized ideas, noting that “it gives you an idea of how you could go about this chronologically” (Participant YY), while some students also commented that ChatGPT writing was very basic and did not reflect college level writing: “I think that structure is very basic” (Participant T). Overall, comments coded in this filter showed the ways students observed the development and order of ideas in ChatGPT texts.

"Ethics" as Filter

The "ethics" as filter code centers students' emphasis on moral implications surrounding using ChatGPT for academic assignments. In our codebook, the language used to describe this form of analysis states, “A basic form of analysis students used. This theme category captures how students used external policies to evaluate the text, and how students expressed ethical concerns about using ChatGPT text instead of their own. Comments in this filter include worries about plagiarism, privacy, and getting “caught” using the technology. "Ethics" as filter shows how students reasoned about the academic and moral consequences of submitting an AI generated text for an assignment. Through their responses, we can further understand how students are thinking through ethical and academic standards with regard to using ChatGPT. As evident in their responses, in some cases there is confidence in their convictions and in other scenarios students are finding the “right” decision to be less straightforward.

Students used this reasoning most frequently when asked the post-task question, “How likely would you be to use this ChatGPT text unaltered as your academic homework?” Many of the student responses were associating the ChatGPT texts with academic integrity by stating that it was not something they [the student] wrote, and therefore they would not turn it in. These types of responses were especially prevalent when students were asked to do the first prompt scenario: “write a literacy narrative.” The literacy narrative was the most personal prompt to the individual student and their responses align with this in terms of how they were thinking about academic integrity. One student said, “...but it’s not something you wrote, so I would not use that as my homework for a literacy narrative about myself.” Another student stated, “...if this is something I turned in, I don’t think it seems very personal.” Students were connecting the impersonal nature of the texts and reasoning about the likelihood of their audience knowing it was not produced by them, leading to entanglements with ethics and academic integrity.

Other students were calling out ethics and academic integrity in more direct ways by stating their concerns about plagiarism. One student said, “I feel like ChatGPT has a voice almost, and it sounds to me like it’s very AI generated. Like a professor receiving this, I feel like would be extremely doubtful that it’s coming from me, and not AI, since it’s been something that professors have to look out for now.”

"Function" as Filter

"Function" as filter was used to code students' responses where they expressed curiosity about the technological capabilities of ChatGPT. This code appeared most often in the debrief interview section when students were asked, “What questions, if any, does ChatGPT raise for you?” Here, students expressed curiosity about ChatGPT’s sources, asking, “Where is the information coming from?", "What biases does it have?”, “How does it pull from the Internet?”, and “What kind of database is it pulling from?” They also wondered about how ChatGPT worked, asking, “What can’t it do?”, “How does it work?”, “Does it have different levels of writing?”, “Does it generate a different response for everyone?”, and “Is it accessible? Is it free?” Finally, students wondered about its functionality in the future. They asked, “How much more advanced will this be in a couple of years?” and “Will it get overused?” Under "function" as filter, students illustrated critical thinking about ChatGPT use and concerns about its impact on their academic and non-academic futures.

"Circumstance" as Filter

In their evaluations of Chat GPT texts, students leveraged many kinds of knowledge related to circumstance. We used the code “circumstance" as filter when students responded by filtering information through their academic identity, their major, or content from a specific class or professor. As we used the code, the team came to realize that this description matched well with models of rhetorical situation since students were thinking about audience, content, purpose, author, and timing.

Indications of this filter included mentions of class content or professor expectations, understanding of genres they were working with, and considerations of how ChatGPT “understood” the assignment. Students also considered how the situation would influence whether or not they would use ChatGPT at all. For example, one student mentioned “if this is a last resort, you know, I'd throw it in there, and I probably still get like a C minus, maybe, but it's really not that good. But for a discussion post this would be good enough.” Another participant noted that the text met the expectations of their genre but that it could have been more useful pedagogically by adding numerical examples, “It includes most of the things that you'd expect in a psychological as abstract. I feel like, maybe a bit more like numbers or specific statistics would be nice, even just generating those for an example, although it has no data to base it on overall.” Finally, another student considered their knowledge of professor expectations, saying, “Sometimes professors have their own things that they want you to remember, or they have their own examples that they want you to remember, and they might hope that you kind of personalize your paper or personalize your assignment to fit the course and fit specifically what you've been learning.”

The results from this filter give us some insight into how students understand the rhetorical situation of academic writing. Students rely on expectations set by instructors about the quality of their work and the extent to which course content should be explicitly included in their writing products. In addition, the way that courses talk about genre served as a tool that students used to determine if ChatGPT could be used. Commonly, discussion posts seemed like an area where there was more comfort using ChatGPT, as opposed to papers where they felt their unique ideas were more highly valued or looked for. A few students noted that they were more likely to use Chat GPT in required foundational courses or general education coursework, “I have used before in an academic class particularly for like any liberal education that are not related to economics for in terms of a time-saving aspect as well as to get a general understanding.” This alerts us that students are less likely to use ChatGPT when they find the information valuable or directly related to their major or area of study. As we see elsewhere, students care about the value of their education, and, interestingly, it seems that when they don’t find value in a class seemingly unrelated to their major they may be more likely to use AI tools to help them save time. Overall, sixty-two student comments were coded in this category.

Discussion

Our sessions with undergraduate students yielded many rich insights. To help make sense of our findings, we return to our overall research questions which included the following:

- How are undergraduate students understanding ChatGPT as an academic writing tool?

- To what extent are students incorporating ChatGPT into their writing product(s)?

- How are students thinking about ChatGPT in their writing process?

How are undergraduate students understanding ChatGPT as an academic writing tool?

Our findings suggest that students in our study saw both the pros and the cons of ChatGPT as an academic writing tool, and they had several questions. In addition, as our filter analysis demonstrated, students had a multidimensional response to ChatGPT. Regarding pros, students in this study consistently rated ChatGPT texts on the high end of the scale when considering expectations and satisfaction. Students also rated ChatGPT highly in terms of “relevance” of information provided in ChatGPT texts. In addition, students used overwhelmingly positive words to describe their experience with ChatGPT texts, mostly in terms of ChatGPT functionality (noted as “function”), citing words such as “time-saving,” “fast,” “convenient,” and “efficient.” Similarly, qualitative student comments coded in the filter of “low order concerns” demonstrated the ways students might view ChatGPT texts uncritically, noting its ability to produce texts quickly, with relevant content, correct grammar and mechanics, and overall clear writing. Perhaps the biggest benefit students noted was the way ChatGPT texts might help them at various points in the writing process, whether in getting started with writing assignments, organizing ideas, or even editing content. Overall, students were impressed with the initial capabilities of ChatGPT in multiple areas: error-free prose, logical organization, relevant content and ideas, and fast production. Said differently, students’ first impressions of ChatGPT texts might reflect an overly positive response to prose that is quickly and clearly produced.

However, these initial reactions to ChatGPT changed as students read ChatGPT texts more closely. As student comments pointed out several concerns and questions about ChatGPT texts. Through qualitative coding, our study categorized these concerns across eight filters, which suggested that students had a multidimensional response to ChatGPT as they considered the tool within larger rhetorical contexts of academic writing. Students most frequently noted a concern about “information literacy,” which was expressed through critiques about information included in the texts, whether it was credible (or even real), where the information came from, and the presence or absence of citations. Students also noted the basic nature of ChatGPT output and its lack of depth or idea development, which we coded through the filter of “logic and organization.” Several students questioned whether ChatGPT texts actually reflected quality college level writing. Students were also concerned about the ethics of using ChatGPT texts, which they expressed through questions or assertions about plagiarism, and the ways in which ChatGPT displaced the voices of students as authors. In addition, regarding ethics, some students expressed concerns about the ways ChatGPT might stifle the learning process, especially if writing is seen as a learning activity in the academy. As one student asked, “what does [ChatGPT] mean for research?” and "what does ChatGPT do to the future of education?" These ethical concerns were connected to student comments coded in the “self and experience” filter, in which students expressed ways they would want to revise or change ChatGPT texts to include more of their individual ideas and thinking. Many students said they would not use ChatGPT produced texts for academic assignments simply because it was not their own work. They emphasized the importance of ownership in their work and even said it would be easier to do the work themselves rather than editing ChatGPT produced texts. As our findings showed, students had a number of questions about ChatGPT including how it worked and whether it was acceptable for use.

To what extent are students incorporating ChatGPT into their writing product(s)?

Our study could not answer this question about using ChatGPT for homework adequately because it presented sample prompts that were hypothetical and not placed in the context of real classes. We had hoped to learn from students whether they would be inclined to integrate ChatGPT texts as their academic homework; because most of the prompts were not connected to any actual class contexts, students could not provide an answer for this question. One task that was closer to academic homework involved the task that asked students to write a prompt that would address a writing assignment they might complete for their major. While we did not require students to add a prompt from an actual class for this task, many of them wrote prompts reflecting work they had done for a class in their major. We did ask students to rate the likelihood that they would use ChatGPT texts “unaltered” as their academic homework; average ratings from students for each of the five ChatGPT texts ranged between 1.5 and 2.5 on a scale of 1 to 5 with 1 being not very likely and 5 being very likely to use texts unaltered. These were the lowest ratings our study recorded, suggesting that students were not overly enthusiastic about using ChatGPT texts for their own homework, or at the very least, they had some significant questions about doing so. While these ratings reflect student caution, again, we cannot be sure of these results due to the overall hypothetical nature of the usability test. We also note that students may have reacted negatively to this question because all research team members were faculty and graduate students from the Writing Studies Department. This reality of the usability sessions may have impacted student answers to this question.

How are students thinking about ChatGPT in their writing process?

Of all the research questions, our study yielded the most information on this question about the writing process. Through ratings of ChatGPT texts, we learned that students highly rated the likelihood that they would use ChatGPT to generate ideas as part of their academic writing process. In addition, these results were supplemented by our coding of qualitative comments in the “process as filter” category, which was the most frequently coded category in our data set.

In response to many of the prompts, students articulated ways that the ChatGPT texts were useful as starting points, with student comments such as: “I would definitely take a look at those sources and maybe use those sources as a jumping point” (Participant G). Similarly, another student responded to the literacy narrative text produced by ChatGPT by saying, “seeing this as an overall like as a story kind of gave me ideas of ... what I would need to do and then I could apply that to my own my own life for a different story that I wanted to tell” (Participant L). Students also commented on ways that ChatGPT would be helpful for creating an outline or initial organization of ideas: “If I was like really struggling, I can see how it'd be helpful just to get an idea of like an outline” (Participant QQ). Students were also aware of the line between idea generation and copying ChatGPT: “I think this is like a good way to generate an idea for like a paper or something. But not necessarily copying and pasting” (Participant WW). Students were impressed by the ways ChatGPT generated ideas, included relevant content, provided initial outlines of organization, and provided a foundation for further writing.

The findings of this study are important because they go against the depiction of ChatGPT as a technology that promotes the written product over the notion of the writing process. As Sid Dobrin (2023) noted, ChatGPT naturally brings up the oft cited binary in writing pedagogy of “product versus process” (p. 22). This binary means that writing can be described both in terms of a finished written product such as a report, a poster, a tweet, or a memo, and in terms of the writing process, which includes writing activities such as prewriting, writing, and rewriting. ChatGPT raises this binary because the technology produces a product, literally in seconds, in response to a specific prompt. This function of ChatGPT immediately raises the question of whether or not students would use ChatGPT as a substitute for the writing process, much like calculators have been said to replace the thinking processes involved in working through complex calculations. It is tempting to think of ChatGPT as a “writing calculator.” As we have conducted this study, we have often heard the questions “has ChatGPT replaced writing?” and “is writing over as we know it”? The results of our study—though exploratory and limited to a small sample—support the ideas that ChatGPT does not replace writing, that it is not a writing calculator, and that it could even be useful in one’s writing process. Student responses noted the usefulness of seeing a sample text from ChatGPT as a way to generate ideas, and also for seeing an initial organizational structure of ideas.

Pedagogical Implications

In this opportune moment, we would like to take a step back to reflect on how this exploratory usability study might inform the teaching of writing. Incidentally, we are all individually writing teachers, and we are keenly interested in the pedagogical implications of using generative AI. Indeed, we agree with the many writing scholars who suggested that ChatGPT provides an opportunity to “re-see” our writing pedagogy. In that spirit, and as writing teachers ourselves, we note some initial pedagogical implications for ChatGPT in writing classrooms. These implications include expanding writing pedagogy to integrate generative AI in writing processes and developing critical AI literacy. We also advocate a critical pedagogical perspective for implementing Generative AI technologies in writing classrooms.

Connecting Generative AI and Writing Processes

As we noted, findings of this study suggested that students appreciated the capabilities of ChatGPT for process-related activities including generating ideas, brainstorming, and outlining. Yet, students also articulated a number of questions about ChatGPT texts, such as doubts about information credibility, lack of depth, and ethical concerns about using ChatGPT. In response, we advocate creating opportunities for students to explore ChatGPT for process activities, but we also suggest centering a critical perspective in doing so. What might this look like? Pedagogical activities related to the writing process could involve facilitating all-class activities or exercises in which students are invited to use ChatGPT at various stages of their processes. The whole class approach is helpful for ensuring that all students have the opportunity to interact with and critically think about ChatGPT. Students could be asked to work in groups to explore ChatGPT, document its suggestions, and reflect on what is most useful and what is not useful about its contributions. Potential prompts to give ChatGPT might include brainstorming ideas on a specific topic or generating outlines. In these exercises, reflection is a key part, as it provides the opportunity for students to critically analyze ChatGPT as they have experienced it. Student groups might point out weaknesses and strengths of ChatGPT suggestions in all-class discussion. Table 1 includes specific suggestions for various process-based class activities that carry this critical perspective.

In addition, and as Graham suggested, ChatGPT strangely provides an opportunity for us to expand our understanding of process-based writing through a “post-process” lens that recognizes the unique attributes and functions of ChatGPT. According to Graham, a post-process pedagogy involving generative AI would view writing as an interaction with an LLM's corpus indirectly, and could center on the practices of fact-checking, curating, prompting, and revising. These practices could be built into classroom activities and assignments, such as by encouraging students to “fact-check” responses produced by ChatGPT, or examining the ways different prompts generate different responses, all with a critical eye. Ultimately, however, ChatGPT teaches us that critical AI pedagogy is to be centered—and not merely affirmed—in writing processes.

Practicing Critical AI Literacy

We find a critical perspective both helpful and necessary in thinking about the pedagogical implications of using ChatGPT. Critical pedagogy centers on the notion of critical consciousness, and here we consider what a “critical AI literacy” might look like. Such a stance would be open to an explicit awareness of generative AI technologies, but would also embrace a critical stance and perspective.

Two concepts come to mind that may help establish a “critical AI literacy.” The first concept is to consider technologies and ethics simultaneously. In Augmentation Technologies and Artificial Intelligence in Technical Communication: Designing Ethical Futures, Ann Hill Duin and Isabel Pedersen (2023) present an “ethical futures framework” that would “reframe professional practice and pedagogy to promote literacies surrounding the ethical design, adoption, and adaptation of augmentation technologies” (“Stronger Relationships, Stronger Programs: Asserting expertise for a generative AI Landscape”, 2023). This framework involves (1) knowledge of augmentation technologies (2) plans for building literacy capacity and (3) strategies for integrating ethical perspectives of adoption and practice. A second example concept involves a “post-digital critical pedagogy,” a pedagogical concept aiming to address the gap between designers and users. In “Postdigital Critical Pedagogy,” Petar Jandric and Sarah Haye (2021) described how this gap can exist: “...tech people did not care about critical pedagogy, and critical pedagogy did not care about tech” (p. 324). They advocated for designers and users to work together to better understand the internal workings of technology and to ask critical questions of it.

Both of these examples help us imagine “critical AI literacy.” Adopting an ethical framework in relation to ChatGPT might mean working to understand the technology and its capabilities while openly acknowledging the ways its use requires scrutiny and verification. In our study, students asked a number of critical questions about ChatGPT, such as “How does it pull information from the internet?”, “How much more advanced will this be in a couple of years?”, “Does it generate a different response for everyone?”, “What kind of database is it pulling from?” These questions showed that student participants are curious about the authenticity, credibility, transparency, and trustworthiness of AI. We see such questions as productive starting points for practicing “critical AI literacy,” and we encourage writing instructors to create spaces and activities in which students can ask these questions.

One exercise might be to ask students to apply an ethical framework to ChatGPT by discussing how and in what situations would various ChatGPT texts would be acceptable. Another exercise might include fact-checking and citation checking exercises which require students to use ChatGPT but also identify and check assertions and citations used in ChatGPT texts. This activity encourages critical reflection about ChatGPT assertions and citations that are seemingly confident; in checking assertions, students can directly question the accuracy of information included in ChatGPT texts. Another suggested exercise is to create requirements or rubrics that articulate criteria for ChatGPT texts. By creating such rubrics, students using this technology may notice that ChatGPT likely cannot produce the depth they are looking for and therefore would not be worth copying word for word. They rubrics may also prime them to engage certain critical thinking skills that they may not naturally bring to texts produced by generative AI. Because ChatGPT texts are initially impressive and appear relatively polished on the surface, encouraging a dive beneath the surface could be pedagogically beneficial.

Table 1. Suggested activities based on student perspectives

| Critical concept | Activity Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Writing Process |

Generating Ideas: As an in-class activity, open ChatGPT and decide on a writing prompt to ask ChatGPT that relates to a writing assignment from class. Enter the prompt and watch ChatGPT create the text. Then divide the class into small groups to further examine the ChatGPT text using discussion questions such as

|

| Developing Ideas: ChatGPT is a chatbot that is designed to dialogue with users about ideas. Ask students to practice articulating an initial prompt on a paper topic, and then have students continue to ask 2-3 additional probing questions of ChatGPT in the same dialogue. Discuss how the continued dialogue may help stimulate ideas or directions for further development. | |

| Creating Outlines: As an in-class activity, open ChatGPT and ask ChatGPT to provide an outline of ideas on a specific writing topic. Break into groups and have each group use the same prompt. Review the text produced by ChatGPT and discuss the proposed organization of ideas and how you might change and/or improve upon it. | |

| Critical AI literacy | Checking Citations: Ask ChatGPT to create a text with citations on a topic of your own interest. Once a text is created by ChatGPT, review each of the citations included in the text and check your institution’s library to see if the citations are accurate. What observations do you have regarding these citations? |

| Fact-checking: Ask ChatGPT to create a text for an argumentative paper. Once a text is created by ChatGPT, circle/underline/highlight assertions made in the paper that you would like to verify. Using credible sources from your institution’s library, engage in fact-checking of the specific assertions included in the ChatGPT text. Write a reflection in which you explain the accuracy of the ChatGPT text shared. |

Conclusion

We conducted this study because we were curious about ChatGPT as a writing technology, and we wanted to learn more about how undergraduate students understood ChatGPT in the context of academic writing. Ultimately, we conducted a usability study that explored uses of ChatGPT by undergraduate students, based on hypothetical academic writing tasks. While our results cannot be generalized in any way, we observed that students in our study noted both strengths and weaknesses of ChatGPT, as well as posing questions about its usage. Overall, these results align well with scholarly discussions of ChatGPT, in which writing scholars have also outlined strengths and weaknesses of ChatGPT technologies and concerns about its use. However, in examining student responses further, we note that questions, concerns, and reactions to ChatGPT signaled that students were practicing critical thinking in their uses of ChatGPT. Their questions reminded us that writing is a rhetorical activity, even when communicated through surface-level prompts, and that considerations of style, content, organization, information literacy, and circumstance still matter. Further, student comments in this exploratory study underscore the need for guidance and clarity around ethical issues such as authorship and plagiarism. As noted earlier, in the course of working on this project we have often heard questions such as “is writing over?” and “do we need to teach writing anymore?” To these questions, we wholeheartedly respond that ChatGPT only increases the importance of writing pedagogies, and we encourage continued attention to AI technologies through a critical perspective.

Download the Data

References

Adler-Kassner, Linda, & Wardle, Elizabeth (Eds.). (2016). Naming what we know: Threshold concepts of Writing Studies. Utah State University Press.

Anson, C. M. & Straume, Ingerid S. (2022). Amazement and trepidation: Implications of AI-based natural language production for the teaching of writing. Journal of Academic Writing, 12(1), 1–9. doi:10.18552/joaw.v12i1.820

Baidoo-Anu, David, & Owusu Ansah, Leticia. (2023). Education in the era of generative artificial intelligence (AI): Understanding the potential benefits of ChatGPT in promoting teaching and learning. Available at SSRN 4337484.

Benedek, Joey, and Miner, Trish. (2002). Measuring desirability: New methods for evaluating desirability in a usability lab setting. Proceedings of UPA 2002 Conference: Humanizing Design. Usability Professionals' Association.

Dobrin, Sid. (2023). Talking about generative AI: A guide for educators. Broadview Press. https://sites.broadviewpress.com/ai/talking/

Duin, Ann Hill, & Pedersen, Isabel. (2023). Augmentation technologies and artificial intelligence in technical communication: Designing ethical futures Routledge.

Duin, Ann Hill, & Pederson, Isabel. (2021). Writing futures: Collaborative, algorithmic, autonomous. Springer Press.

Graham, Scott S. (2023). Post-process but not post-writing: Large language models and a future For composition pedagogy. Composition Studies, 51(1), 162–168.

Floridi, Luciano. (2023). AI as agency without intelligence: On ChatGPT, large language models, and other generative models. Philosophy & Technology, 36(1), 15.

Johnson, Gavin P. (2023). Don’t act like you forgot: Approaching another "literacy crisis" by (Re)considering what we know about teaching writing with and through technologies. Composition Studies, 51(1), 169–175.

McAndrew, Don, and Reigstad, Tom. (2001). Tutoring writing: A practical guide for conferences. Heinemann.

MLA-CCCC Joint Task Force on Writing and AI (2023). MLA-CCCC joint task force on writing and AI working paper: Overview of the issues, statement of principles, and recommendations.

Vee, Annette. (2023). Large language models write answers. Composition Studies 51(1), 176–181.